Big E Wants to Write More Chapters in History of 4-H Beef Program

Raising the Steaks

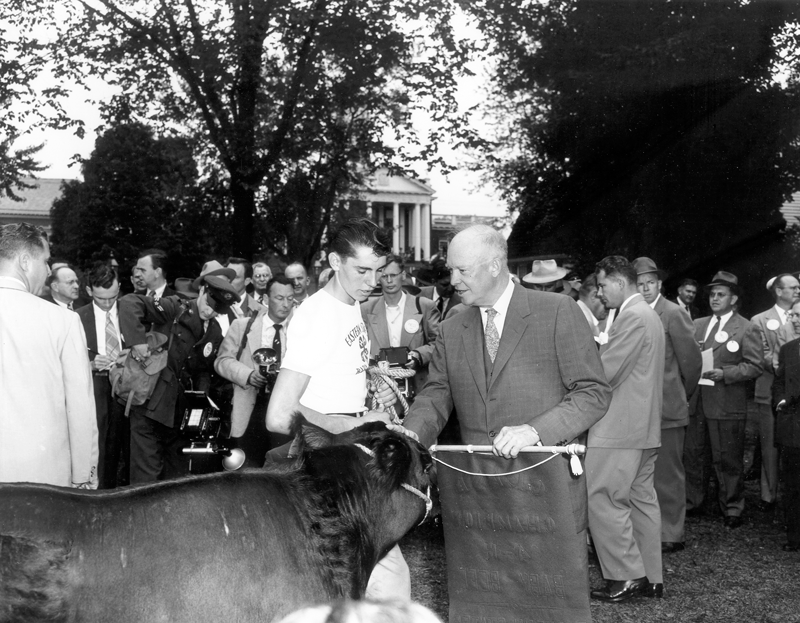

The iconic photo of President Eisenhower from the 1953 Big E. He was there to check in on the steer raised on his farm in Pennsylvania.

It is one of the most iconic photos taken during the 101-year history of the Big E.

Captured in 1953, it depicts President Dwight Eisenhower (the only sitting president to ever visit the Big E during the fair) meeting with Fred Scoralick, age 18, from Dutchess County, N.Y., that year’s winner of the 4-H Beef program, and his grand champion steer.

By now, most have seen the image — it was one of several to gain considerable exposure (pun intended) during the Big E’s various centennial happenings a year ago, and it was among a handful that made the cover of a commemorative book marking that occasion. But most don’t know the full story behind the photo, said Donna Woolam, who relates it often.

As Woolam, director of Agriculture and Education for the Big E, tells it, Eisenhower, then nine months into his first term in the White House, didn’t just happen by the Big E that year, and he had much more than casual interest in the 4-H Beef program and the winning black angus steer in question.

Indeed, it was raised on his farm just outside Gettysburg, Pa. — not far from the Civil War battlefield and now a national historic site — and sold to Scoralick’s family with the intention of entering it in the 4-H competition.

“He was the breeder of that steer, and he was here to see the animal being shown,” said Woolam. “That’s why he came.”

The story behind the Eisenhower photo falls into the category of ‘little-known history,’ and that phrase pretty much sums up the 4-H Beef program, or the Baby Beef program, as it was known in its early years. There is considerable history attached to it — 86 years of it, to be exact — but it is known to a relative few, meaning those who participate and those who support agriculture and events like this one.

Woolam and Big E President Gene Cassidy would like to make this a bigger constituency. More importantly, though — and this goal is directly related to that first one — they want to write many more chapters in the history of the beef program.

And that will be a challenging assignment as agriculture continues to decline as a business — and as part of the culture and landscape — in the Northeast.

“In this day and age, especially in urban areas, I wish there were more people better informed about 4-H; it should be part of the curriculum,” Cassidy said. “It’s important for our children, and for all of us, to have food literacy; it’s important for our health, and it’s important for our economy.”

Raising the stakes (or steaks, if you will), Cassidy went so far as to issue a call of support for the many aspects of the 4-H Beef program. They include not only the competition, but the auction of this year’s steers, where the beef is often contributed to area community food pantries, as the Big E itself did last year when it bought one of the steers and donated the meat to the West Springfield Parish Cupboard.

“The Big E challenges you and your business … SUPPORT NEW ENGLAND AGRICULTURE,” read the ad in the Sept. 4 issue of BusinessWest, which featured all those capital letters for emphasis and went on provide details of the auction, set for Sept. 25 at the Big E’s Mallory Agriculture Complex.

Cassidy is hoping the challenge will be answered, and, overall, he’s also hopeful that more business owners and area residents will realize the all-too-real threats to agriculture in this part of the country and be part of efforts to preserve what’s left, cherish those traditions (and businesses), and secure a future for this sector of the economy.

Meat and Greet

Look closely at that photo from 1953, and you’ll notice that President Eisenhower is holding one of Scoralick’s prizes from that year’s competition — the winner’s banner, or ribbon.

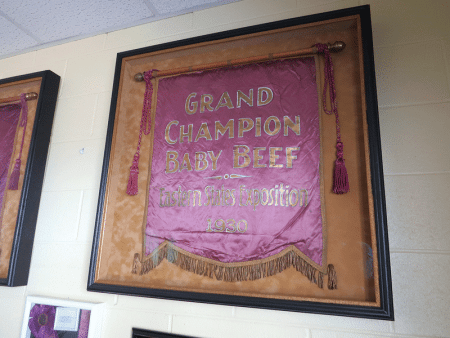

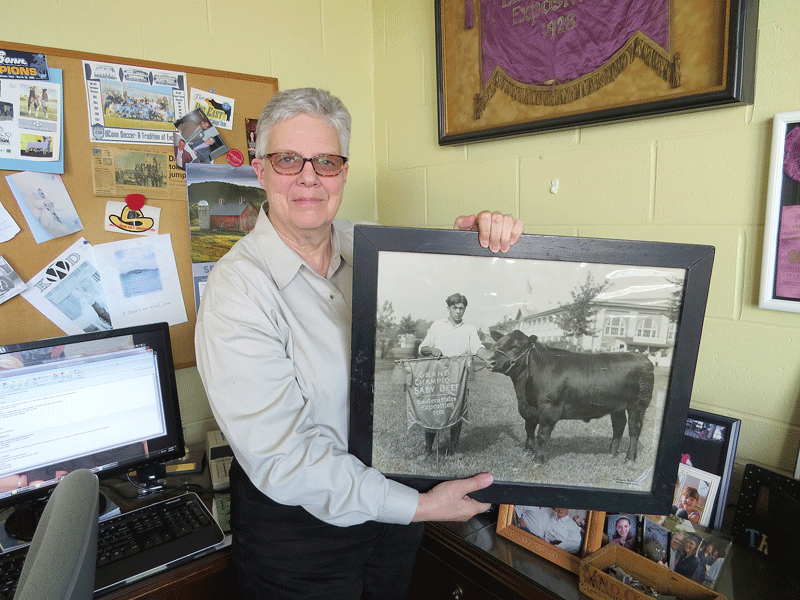

You can’t read it, because it’s facing the wrong way, but it has the words ‘Grand Champion 4-H Beef ’ and ‘Eastern States Exposition’ as well as the year on there somewhere. These colorful, bright-purple awards have become part of the history of the competition, said Woolam, who has two of them mounted in frames hanging on the back wall of her office.

They were a gift were a gift from the family of Lee Jenks, from Agawam, and they represent his winning achievements in what was then the Baby Beef competition in both 1928 and 1930.

“The family walked in here one fair and said that these needed to hang here, in the Mallory, where it all happened,” said Woolam, referring to not only ‘grand champion’ banners but also a photo of Lee, who passed away several years ago, with one of his prized steers. “We’re very proud to have them.”

As are the owners of the other 85-odd champion banners that have been handed out over the years, she said, adding that they have become keepsakes and are often prominently displayed. Winning the beef competition is a proud moment, she went on, so much so that, when a past champion passes away, their accomplishments at the Big E are almost always noted in his or her obituary.

But over time, and especially in recent years, the 4-H Beef program has become much more than a competition among dozens of young people ages 12 to 18. Indeed, it has become everything from a vehicle for helping to feed to those in need to a way for participants to earn needed money for college (and often a degree in agriculture science), to a showcase for a declining agriculture sector, especially in the Northeast.

Overall, the competition hasn’t changed much since it was started in 1921, said Woolam. Young heifers and steers are acquired from breeders (like Eisenhower) and raised for roughly 10 or 11 months prior to the Big E in which they will compete. The heifers are raised as breeding stock, while the steers are destined for the aforementioned auction, with the meat going to the buyers or designated charities.

The animals, which represent a number of different breeds, are judged against industry standards, Woolam explained, adding that this year’s judge hails from Tennessee.

“He’ll be looking for animals with a lot of natural muscling, a lot of structural soundness, visual eye appeal, and more,” she explained, adding that many of the competing livestock are crossbreeds.

This year, 45 steers are expected to be entered, and perhaps 30 of those will be sold, she went on, adding that the winning animal could fetch $5 or more per pound, and last year, the average selling price for the 24 steers that went to auction was $2.70 per pound.

Participants, meaning the young people that raise the animals, are from the six New England states and Dutchess County in the southeastern part of New York. The returning champion (she actually won in both 2015 and 2016) is Olivia Oatley, from Exeter, R.I. She has kept the champion’s banner in the family — her brother won a few times before she did — and has three steers in this year’s competition.

The program, like all 4-H endeavors, is educational in nature, said Woolam, adding that, during the Big E, participants will take part in a host of programs and competitions to test their abilities and knowledge of the cattle industry.

And while participants are furthering their education when it comes to agriculture and agribusiness, Cassidy hopes the public can do the same.

“With our lack of food literacy, there’s such a misunderstanding about food product,” he explained. “And this breeds activism, which harms agriculture.”

As an example, he cited the referendum question on last year’s ballot in Massachusetts that would prohibit sales within the state of eggs from caged hens. It passed, and the measure will take effect in 2021, said Cassidy, who expects that it will put the only remaining poultry farm in the state out of business and significantly raise the price of eggs in the Bay State.

Donna Woolam shows off the photo of Lee Jenks, Baby Beef competition winner in 1928 and 1930, that was gifted to the Big E.

“In California, where they passed a similar referendum several years ago, a dozen eggs cost three times what they do in Massachusetts,” he explained. “People here can buy a dozen eggs now for $1.65; that ballot question will take the price to way over $3.”

Cassidy said he sees a direct parallel between programs like 4-H and Future Farmers of America and food literacy. And that’s why he maintains that initiatives like the 4-H Beef program must not only continue, but garner additional support — at the auction, and in other ways as well.

Woolam agreed.

“This is a program with a lot of history,” she told BusinessWest. “And we hope it’s a program that will continue for many more years.”

Gaining Ground

Take one more look at the photo of President Eisenhower, and you’ll notice the large and very well-dressed press contingent (this was 1953, remember) in the background.

It would take a sitting president on the Big E grounds for the 4-H Beef competition and the grand champion steer to get anything approaching that kind of attention, and Gene Cassidy knows that.

That’s not exactly what he’s looking for. He is looking for a little more attention, some additional support, and a better understanding of the business of agriculture and its importance to the region.

In short, he’s looking to secure opportunities to create more — make that much more — little-known history.

George O’Brien can be reached at [email protected]