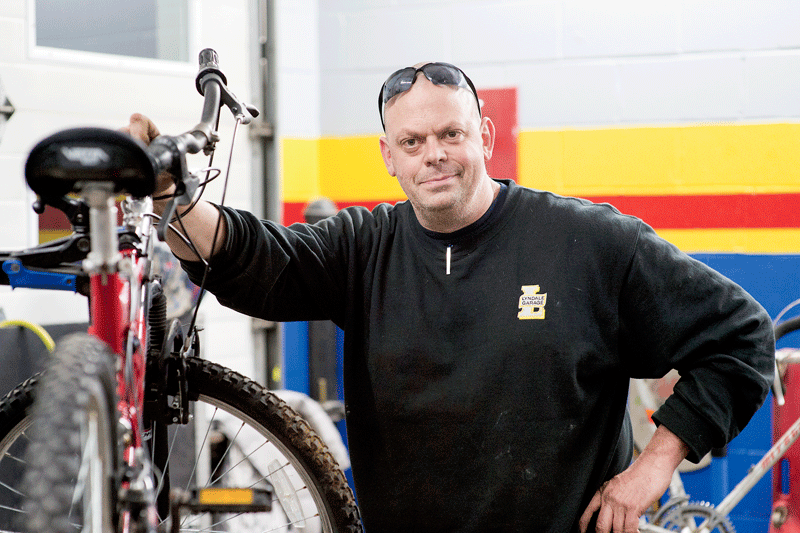

Bob ‘the Bike Man’ Charland: Founder of Pedal Thru Youth

The Bike Man’s Story Has Been a Truly Inspirational Ride

Bob Charland was already having enough trouble fitting everything on his plate into a 24-hour day.

Bob Charland was already having enough trouble fitting everything on his plate into a 24-hour day.

He had his full-time job, as an auto mechanic at the Lyndale Garage in Springfield, and he was also teaching what he calls “deaf automotive” for students attending Willie Ross School for the Deaf. There were also his many endeavors within the community — primarily his work repairing bicycles and putting them in the hands of underprivileged children across the region, but also his latest venture, what he calls “safety bags” for the homeless and other people in need.

And then, there were also a growing number of medical appointments and tests as he grappled with a brain disorder that remains officially undiagnosed but is considered terminal.

With all that, he admits he was only getting maybe three hours of sleep each day, something he’s learned to live with. But then, the schedule got even more crowded.

He had to start making room for the media. Lots of room.

The local television stations were calling regularly as his donations of bicycles and other endeavors escalated; community newspapers wanted his time to talk about his work in their cities and towns. He’s been on Ludlow public television and a radio station in Boston. Then, the national news networks, including CNN and Fox News, picked up the story. Ellen DeGeneres’ people called. And, yes, BusinessWest wanted a few hours to discuss his selection as a Difference Maker for 2018.

Most time-consuming, however, was a documentary, titled My Last Days, on his life and deeds undertaken by the CW Network and due to be aired this month. The company had already demanded several hours from Charland for the project, and then it came asking for more.

But the ‘Bike Man,’ or ‘Bicycle Bob,’ as he’s called by different constituencies, told them they couldn’t have it. They repeated the request, and he again told them ‘no.’

So they went around Charland to his employer at the garage, told him they would compensate the company for his time lost, and finally locked him in.

And it was certainly worth it to get him out for that additional taping session, as as we’ll see in a minute.

Meanwhile, there’s a reason why Charland now has to make so such time for the media. As they say in the business, this isn’t just a story; it’s a great story.

The individual pieces are themselves compelling — the bicycle program and how it’s grown; his new work within the community, his terminal illness, and his decision to not only go on living but ramp up his work across the region; the press; and the response from that same community to all of the above. But the package … it’s captivating, and, far more importantly, inspiring, which is what really drives Charland in everything he does.

Indeed, he said people have responded to his story in ways he might have hoped, but probably couldn’t have imagined. It has left people compelled to find their own ways to help, to live life to the fullest, and, in many cases, to simply meet the Bike Man.

“I got an e-mail from a guy who wants me to come out and meet his mom,” Charland said as he reached for his phone so he could quote it directly rather than paraphrase, which he did.

“He says ‘Rob, thanks for being such an inspiration with all you’re doing. I have followed your bike story for about a year now. My stepmom, who is basically my real mom when my mother backed out and left us, is terminally ill with stage-4 bone cancer. You give a different, great, positive outlook on things. My stepmom appreciates all you do; you’re an inspiration to all. Thank you.’

“So I told him I’d come out and meet her,” he went on, adding that this was another thing he would gladly make time to do.

Maybe the most compelling part of this story is that his illness hasn’t slowed him down one bit. In fact, it has made him more determined — if that’s actually possible — to cram even more into each day.

“I’m not going to let it slow me down,” he told BusinessWest with tangible conviction in his voice. “Every day that I get up, I can make a difference in someone’s life, and that’s what I’m going to do; that’s what drives me.”

Those few words, more than any that would follow or that came before, make it abundantly clear why the Bike Man will be at the podium at the Log Cabin on March 22 to accept a Difference Maker plaque.

Chain of Events

As noted earlier, those documentary makers had a very good reason for being so persistent in wanting Charland back for another round of filming, or still photos, as they told him. But as things turned out, he didn’t really spend too much time in front of the camera.

For an explanation, well, as they do in a good documentary, we’ll let him do the talking.

“They told me to bring a couple of changes of clothes with me because they wanted to get some photos in a few different places,” he recalled. “We took my truck and ended up in Bernardston, a beautiful little town.

Bob Charland says his terminal illness has inspired him to try to pack even more into each day and find new ways to give back.

“Going back to when we first started with this, they asked me a lot of questions, and one of them was, ‘what’s one thing from your childhood that you regret not doing?’ And I said, ‘me and my dad, who’s really my stepdad, but he raised me, always said we were going to go camping together — just him and I — and it never happened,’” he went on. “So we’re there in Bernardston, and I have no idea where we’re going. The next thing you know, we go across a wooden bridge out in the woods to a cabin right on a lake. I didn’t think anything of it.

“The guy told me the camera crew would be there in a while, and that I should just get out, walk around, and check out the place,” Charland continued. “I look around … there’s a nice dock that went out on the water; I saw a guy sitting on the end of the dock. It turned out to be my father. I was shocked that he was there, and I didn’t know why. He just turned to me and said, ‘are you going to give me a hug, boy, or not?’”

The two would spend the next week having that camping trip they never went on decades ago, expressing as much emotion — and talking to each other more — in that short time than they probably had in all those years leading up to that moment.

The documentary producer left the two there with a camera operator, who would shoot a little footage and then leave them alone for the week. More importantly, though, he left them with some thoughts about why they were there.

Put simply, the two had done so much for others throughout their lives; now it was time for someone to do something for them.

And with that, it might be best to tell more of the story of how that documentary — and that bonding between father and son — came to be. We begin, again, like a good documentary, at the place where the story starts to come into focus.

For Charland, that was when his daughter, now 23, was raped by her mother’s boyfriend when she was 9.

“At that point, I was given full custody,” he explained. “The courts and the counselors had told me to get her involved in as many things as possible because of what happened to her. So she got involved — and I got involved.”

Indeed, when the leader of the Girl Scout troop his daughter joined decided she couldn’t continue in that role, Charland took over. Not for a little while, but 10 or 11 years, by his count.

“I was cookie coach — I have all the T-shirts from all the years I did it,” he said, adding that, as you might have guessed, he was one of the first male leaders of a Girl Scout troop in this region.

He also started coaching girls softball at Holy Cross Parish School in Springfield — another assignment that lasted a decade or so — among other work in the community, usually alongside his daughter.

“I was afraid to leave her anywhere as a result of what happened to her,” he went on, adding quickly that, because he had no child support, he was also working several jobs — the one at the shop, as a bouncer at an area club a few nights a week, and as a chef at A Touch of Garlic restaurant.

Springfield Mayor Domenic Sarno says Bob Charland has become an inspiration and a role model at a time when the world — and Springfield — need more of such individuals.

Eventually, his daughter grew out of Girl Scouts, softball, and other activities, and this development left a void of sorts and something Charland’s seemingly never had much of — spare time.

He filled the void and the hours in the day in various ways. Teaching automotive skills to deaf children — after learning sign language — become one outlet (students are bused to the Lyndale Garage). And eventually there was what he came to call simply “the bike thing.”

Into a Higher Gear

It started, sort of, when his daughter was in middle school. One of her guidance counselors was a nun who would bring Charland a few bikes to fix up for some of her students. And it grew from there.

As most everyone in the region knows by now, thanks to all that press he’s been getting, the bike thing has become not only a Springfield phenomenon, but a regional one as well. Charland has given away bikes in several area communities, including Hartford, and to nearly a dozen schools. To organize it all, he created a nonprofit called Pedal Thru Youth.

In the beginning, Charland would pay for bikes out of his own pocket, but as the news spread, the donations started to flow in, even from some of the neurologists who have treated him. So did other forms of support; AAA donates a helmet for every bike donated, local police departments and the Sheriff’s Department are heavily involved (with bike-safety instruction and other initiatives), and the city of Springfield and Columbia Gas have both donated space to warehouse bicycles while they’re being fixed up and readied for beneficiaries.

“We target the most poverty-stricken areas throughout Western Mass., and they see the worst of the police departments,” Charland said while explaining that there’s much more to this than a child getting a bike. “If these kids see a cop down on their level fitting them with a helmet and helping them adjust their seat or the handlebars, they’re going to look at these officers in a more positive light.”

It’s a great story, but what makes it more remarkable is that it doesn’t take place in a vacuum. It plays out amid — and largely because of — a worsening medical condition that has left Charland quite unsure of how much time he has left and what his quality of life will be.

Back in 2011, around when the bike thing started picking up some speed, Charland suffered what he called a minor stroke. An MRI discovered an arachnoid cyst in his left cerebellum, which specialists would attribute to a concussion he suffered when he was struck in the back of the head by someone wielding a baseball bat after leaving the club following his bouncing shift.

“The cyst grew to protect my brain, and they noticed a lot of dead spots,” Charland explained. “Over the years, things got progressively worse. There were times I would get extremely dizzy, I would stutter, other times my hands would shake. I was having tremors … and the right side of my body was shaking a lot.”

Doctors have never given him an official diagnosis, but they suspect Charland has CTE (chronic traumatic encephalopathy), the condition that has affected dozens, if not hundreds, of pro football players and other athletes.

“They say they think that’s what it is,” he told BusinessWest. “But they can’t give me 100% diagnosis until post-mortem. So I jokingly said to them, ‘call me when I’m dead and let me know.’”

After that diagnosis, or non-diagnosis, as the case may be, Charland went to Vermont, one of three states in the country to enact a death-with-dignity law, and quickly put his affairs in order, deciding, among other things, what to do with his five trucks.

What brought him back to Springfield early last year was a request from a Springfield school administrator for bicycles he might be able to donate, one that he fulfilled.

And that donation became a news story, one that fueled others and also took the bike thing to new heights.

By Easter morning, Charland had 25 to 30 bikes repaired and ready for distribution. He called a friend who was also a Chicopee police officer and suggested the two go to one of the city’s poorer neighborhoods and donate the bikes.

“We started knocking on doors and handing bikes out,” he said, adding that the local TV crews were tipped off and came to report the developing story.

More press led to more requests for bicycles, which led to more donations, which led to more press, which led to … you get the idea. Soon, the story had traveled literally around the world.

Braking News

And then, remarkably — or not, considering the individual in question — the story got even better. Indeed, Charland kept looking for new ways to give back and pack more into his typical day.

Which brings us to those safety bags mentioned earlier. They’re also called ‘necessity bags,’ and that might be a more accurate description, because that’s what they contain — hats, gloves, scarves, toothpaste, a toothbrush, some toiletries, protein shakes, granola bars, and more.

He started with the Massachusetts State Police, who would give them to homeless individuals and others deemed in need of such a package. And it spread from there. The Springfield Police even have a name for it — Operation Basic Necessities — and Charland has outfitted each cruiser with two bags, each gender-specific; once a bag is given out, he replenishes it. He’s also donated bags to the Connecticut State Police and the Hampden County’s Sheriff’s Department. Last fall, he attended the National Police Chiefs Assoc. convention, and fielded requests from more departments for the bags.

The bags were intended to meet a recognized need, to fill a void, he explained, adding that he has always been driven to step in and address such deficiencies.

With all the press he’s been getting, Charland started keeping a scrapbook of sorts. Actually, it’s just a manila folder with some press clippings, letters and notes from elected leaders (U.S. Rep. Richard Neal sent him one, state Rep. John Velis did as well, and Springfield Mayor Domenic Sarno has corresponded on something approaching a regular basis), a proclamation or two, and some certificates from groups ranging from the Springfield Thunderbirds to the Center for Human Development.

There’s also a handwritten note, source unknown, that says, in large capital letters, “THANKS BOB FOR ALL YOU DO.”

Collectively, the contents of that manila folder speak to probably the best part of this remarkable story — the manner in which Charland is connecting with people, inspiring them, and, in some cases, getting them involved as well.

Sarno spoke about it as he talked with BusinessWest about one of his now-best-known constituents. Specifically, he discussed how the Bike Man replied to one of his correspondences wishing him good luck and good health.

“He called me and said, ‘mayor I need a little help … I just wanted to help some kids with bikes, but this is really blossoming,’” Sarno recalled, adding that he helped arrange some storage space.

Overall, Sarno said Charland’s work with children and the police is a positive development, but more important is his emergence as a role model at a time when society sorely needs some.

“At this time of reality TV, when negativity sells, and ‘if it bleeds, it leads,’ this story resonates with people,” he told BusinessWest. “He’s like the Energizer bunny; he keeps going and going and going, and he never says, ‘woe is me.’ His attitude is so positive — it’s not about himself, it’s about making a better opportunity for these kids and showing that people do care. He’s a one-man wrecking crew.”

Charland’s ability to inspire others and enrich their lives with more than a two-wheeler is perhaps best summed up in the words on the latest addition to that scrapbook, a plaque declaring him the winner of the Citizen Award in conjunction with the Safe Neighborhood Initiative. It reads, in part:

“You have taken a learned skill and turned it into an everlasting blessing for children. They will carry the value of giving back to the community into adulthood and will in turn help nurture the development of our community, making your work immortal.”

The Ride Stuff

Sarno is known for being prompt and prolific with correspondences of thanks and support to individuals and groups over the years, and Charland is no exception.

The mayor has written him several times, as noted, usually after another press report of his work. The typical missive is part thank-you letter, part note of encouragement. Here’s the one sent last June, prompted by little more, it seems, than a desire to stay in touch:

“Thinking of you and just wanted to drop you a note of good health, encouragement, and thanks. So heartwarming what you are doing for our kids. You’re making their dreams/miracles come true. You’re in my thoughts and prayers … that a miracle can and will happen for you.”

With those words, he essentially spoke for an entire region about someone who truly defines that phrase Difference Maker.

George O’Brien can be reached at [email protected]