Building Collaboration

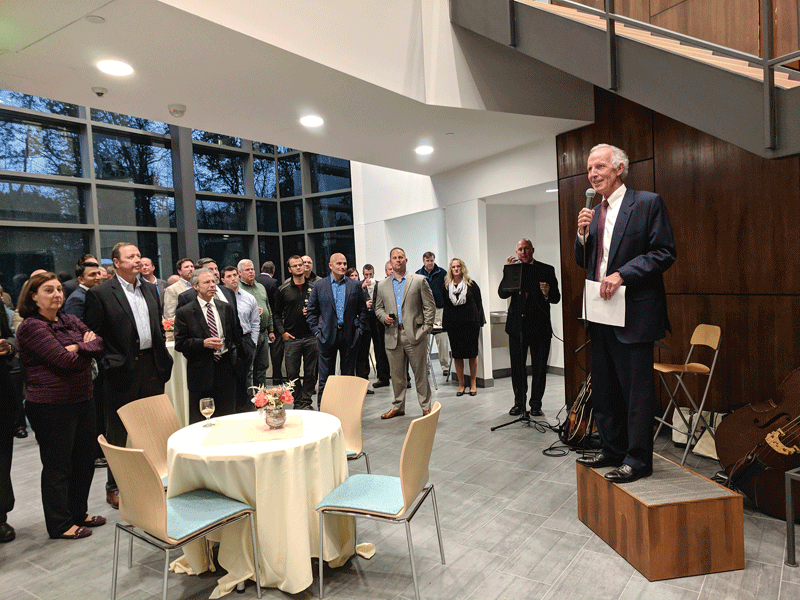

The O’Connell Companies has a new home in Holyoke (above), replacing the previous headquarters (below) of more than a century.

The O’Connell Companies traces its history in Holyoke back to 1879, when Daniel O’Connell founded the construction company that eventually branched into property design, management, development, and much more. For more than a century, the company was housed in limited quarters on Hampden Street, but a new headquarters on Kelly Way offers more space, amenities, and opportunities for what one of the firm’s executives called “cross-fertilization.”

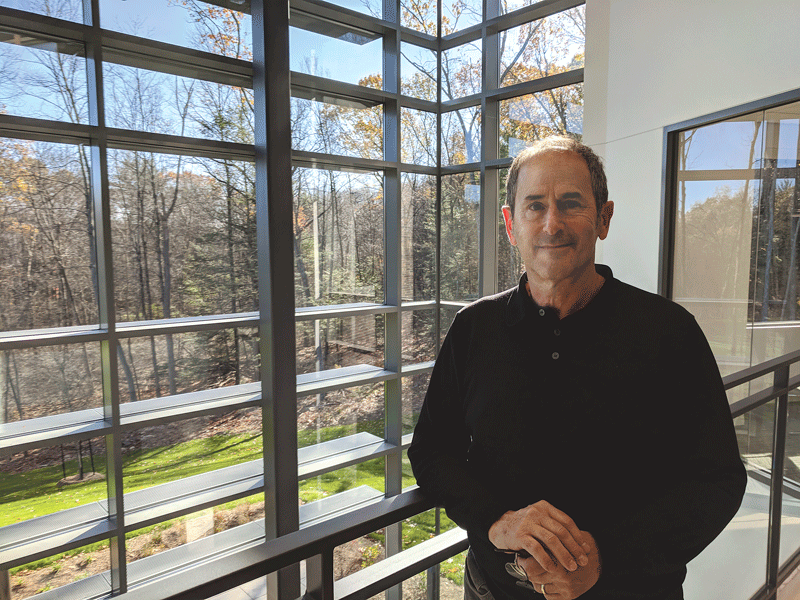

In the conference room where Andrew Crystal sat down with BusinessWest recently, the only piece of artwork currently hanging up is a stylized, brightly hued BIM (building information modeling) image of the new headquarters of the O’Connell Companies, located on Kelly Way in Holyoke. On the opposite wall hangs a cutting-edge, multi-screen array for both displaying information during meetings and videoconferencing with other parties.

The room’s long, wooden table, however, is one of the only pieces brought over from the former O’Connell HQ on Hampden Street. The restored table represents some of the connective fiber between old and new that the company wanted its new home to represent, said Crystal, vice president of O’Connell Development Group.

“We’ve managed to incorporate some history,” he said, also referencing a set of century-old, meticulously handwritten balance sheets framed on the wall of another wing, where the accountants work. “The company does have a very long, interesting story, so we tried to preserve some of the history and the culture of the company. That was very important in the design of this.”

Otherwise, the new headquarters, situated on a seven-acre parcel in the woods off Bobala Road, is rife with modern touches, starting with the striking central atrium that connects the wings that house various divisions — O’Connell Development Group, Daniel O’Connell’s Sons (construction), Appleton Corp. (property management), and New England Fertilizer Co. (biosolids management).

The atrium is awash in natural light and features tables and chairs toward the back, along with a kitchen and coffee bar. “We wanted to create some space for people to mingle informally, share a meal or coffee break together, with the intent of getting to know each other and, more important, cross-fertilize, because everything we do is related,” Crystal said. “We design, develop, finance, build, and manage buildings, roads, and bridges — it’s all interrelated for me.”

One of the goals of the new building is to bring together all the company’s divisions under one roof; Appleton previously had its own space on Suffolk Street in Holyoke, while the Hampden Street facility that housed the others had long been insufficient.

“It was an old, tired building, and we had looked at renovating it,” Crystal said. “But, to continue to be a great work environment for present employees, but also with an eye toward the future, it made sense to move to a new location and to have everything under one roof. There’s nothing like being in the same building.”

Dennis Fitzpatrick, president and CEO of the O’Connell Companies, said as much when he addressed hundreds of visitors at a recent open house, noting that it’s been more than a century since the firm dedicated a new headquarters.

Andrew Crystal stands on the walkway overlooking the sunlit central atrium and the woods behind the property.

“When we started this project, our hope was that we could create a modern, contemporary office building where we could more effectively carry out our daily work,” he said. “We wanted improved functionality, a higher level of comfort, and we wanted a few more amenities. We hope that our new headquarters will cultivate a work environment that supports and further develops the spirit and cuture that has made this organization as successful as it has been for as long as it has been.”

For this month’s focus on commercial real estate, BusinessWest paid a visit to Kelly Way to check out the results of that effort.

Forward Thinking

The intent, Crystal said, was to house the company’s various divisions in a modern, energy-efficient, healthy environment. “We wanted to be conscientious about the environment in terms of energy efficiency and how we treated the land when we sited the building and took the trees down. And we wanted to preserve and enhance the corporate culture that exists here, which is why we created this atrium space in the middle of the building.”

He has heard of multiple incidents recently of long-time O’Connell employees meeting in person for the first time, which means the design is working.

“Part of the design is to create space and an environment that encourages people to collaborate and work together between companies,” he explained. “It was also done with an eye toward creating a great workplace for employees — not just the employees we have, but as an incentive to attract younger employees. Things like the atrium and a shared coffee bar, and a fitness room downstairs with showers — these are things that younger workers want, and it’s a competitive environment to attract talent.”

As for the subdued exterior of the building, Crystal said he had a specific vision for how the dark-bricked façade would interact with the woods around it.

“We wanted a brick building, but we wanted something that was more unique than red brick, that was an elegant blend with the surroundings,” he explained. “We went through quite a few designs, looking at various mixes of bricks. We’re very pleased with the result; whether it’s a bright, sunny day or an overcast, rainy day, the building really fits into the surrounding environment.”

The natural light that pours in from the building’s tall windows brings aesthetic appeal as well, but doubles as an energy-efficient element — one of many, he explained. “We chose not to get LEED-certified, but the criteria in LEED buildings drove a lot of the decisions around energy efficiency, water efficiency, quality of the air people breathe, and the views people have to the exterior.”

Dennis Fitzpatrick, addressing open-house attendees, said it was “high time” O’Connell’s own home reflected some of the modern design elements it was using in its clients’ projects.

For instance, he continued, “all the light fixtures are LED, and all are on occupancy sensors. We have a high-efficiency boiler for heating, and we have energy-recovery ventilation, so when air is exhausted from the building, we recover some of the energy from the air and reuse it.”

Crystal added that the environmentally friendly focus extended to the outdoors, where the building was positioned in such a way that preserved the more mature trees around its perimeter. The plan is to develop some walking trails through the wooded surroundings by next summer. For now, a large outdoor patio overlooks the grounds behind the atrium. “So if you’re on your laptop on a beautiful day, why not sit outside with the beautiful woods and do your work?”

A freshly installed bocce court is another way to help employees enjoy the outdoors during the warmer months, he added. “Again, we want to encourage people to stay after work and recreate and get to know each other. One of our goals is to create a sense of community among employees.”

Daily Impact

In short, Crystal and his development team — which included architectural firm Amenta Emma and a host of contractors and subcontractors from Western Mass. — are firm believers that a building’s design and environment affect both productivity and employee behavior.

“One goal was to encourage collaboration, innovation, and cross-fertilization,” he said, referring not only to the shared atrium, but formal conference rooms in each wing and the open layout of each division, with offices ringing a shared bank of workstations. Each wing also features a small, private room with a phone for employees in the shared space to make private calls.

A color palette heavy on light grays and whites, with a bold splash of blue ringing some walls, was designed to promote brightness and productivity, and the rainbows that occasionally appear in the glass and white-ash floors when the sun hits the atrium’s huge rear windows is “one of those unanticipated surprises,” Crystal noted.

“People seem happy,” he said. “I think the employees are happy to be here. Having a fun, modern, efficient environment to work in is an important piece of that.”

As the company’s president, Fitzpatrick certainly understands the importance of keeping everyone happy.

“Part of our culture is our people working together to come up with creative, innovative solutions to the challenges and risks that our company faces in our daily business,” he told the crowd at the open house.

“At the O’Connell Companies, we all care very deeply about the details,” he went on. “We care about what happens when plane X meets plane Y. We care about quality, and we care a lot about the feel, the sense that you have when you’re in a building, and I wanted this building to represent that. I wanted it to reflect the kind of quality that we hold ourselves accountable for when we go out and develop, build, and manage an asset for someone else. It was high time that our home reflected some of the ones that we were building.”

As Crystal walked BusinessWest past what’s called the Founder’s Room — a formal conference space on the second floor with a black walnut table built by Jonah Zuckerman of City Joinery in Holyoke — he reflected again on how the company’s history in the Paper City impacts how it does business today, and how its new headquarters fits into that history going forward.

“The real value this company has is its intellectual capital,” he said. “Yes, we own real estate, and we own equipment, but what makes the company unique is its intellectual capital, and by locating all our employees in the same building and actively promoting interactions and collaboration, I think the company benefits. That’s what we hoped to accomplish by relocating.”

Joseph Bednar can be reached at [email protected]

When Peter Wirth and his business partner, Rich Hesse, commenced their search for a site to locate a Mercedes dealership that would serve Western Mass. and Northern Conn., they started, well, where one might think they would start — Riverdale Street in West Springfield.

When Peter Wirth and his business partner, Rich Hesse, commenced their search for a site to locate a Mercedes dealership that would serve Western Mass. and Northern Conn., they started, well, where one might think they would start — Riverdale Street in West Springfield.

Long touted as the potential site of a boutique hotel, the historic building at 13-31 Elm St., bordering Springfield’s Court Square, is now the focus of a different vision, due to MGM Springfield’s own hotel plans. Peter Picknelly’s OPAL Real Estate Group now sees the property as a mixed-use center for retail, office space, and market-rate housing, and is working with the city to make the $40 million project a reality — and yet another key element to Springfield’s downtown revival.

Long touted as the potential site of a boutique hotel, the historic building at 13-31 Elm St., bordering Springfield’s Court Square, is now the focus of a different vision, due to MGM Springfield’s own hotel plans. Peter Picknelly’s OPAL Real Estate Group now sees the property as a mixed-use center for retail, office space, and market-rate housing, and is working with the city to make the $40 million project a reality — and yet another key element to Springfield’s downtown revival.