Match Makers

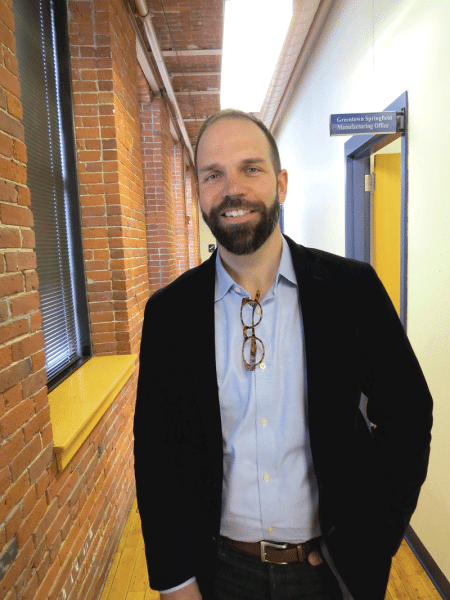

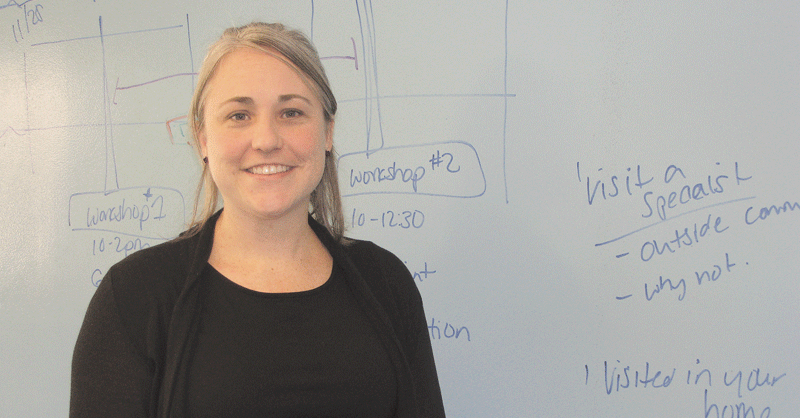

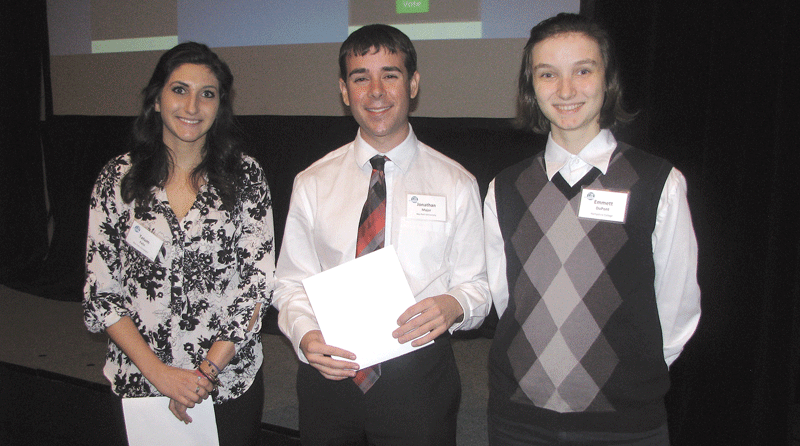

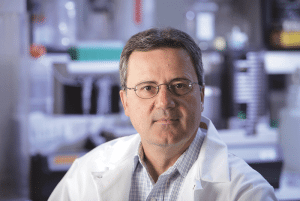

Hope Ross Gibaldi, executive director of Valley Venture Mentors (left), and her mentee, entrepreneur Lenore Abare.

Lenore Abare was familiar with Valley Venture Mentors (VVM) and even attended one of its events when she was dabbling with the idea of becoming an entrepreneur a few years ago.

“It all stayed in the back of my mind,” she said. “Now that I’m full-blown running my own consulting business, I knew it would be really important to align with other like-minded women who are hopefully beyond me, and learn from other people’s experiences.”

So she reached out to Women Innovators & Trailblazers, a VVM-affiliated program that matches professional women in mentor-mentee relationships. She was accepted into the program and found out last week that she was matched with Hope Ross Gibaldi, VVM’s executive director.

Seven years ago, WIT was the brainchild of Liz Roberts, then-CEO of VVM; Ann Burke, vice president of the Western Massachusetts Economic Development Council, and a number of other women, Gibaldi told BusinessWest.

“It arose out of the need for female-based mentorships and knowing there’s such great human capital here in the Valley. There are so many women who are seeking mentorship. And it’s not that we feel women can’t benefit from male mentorship, but there’s a unique connection and bond when women are mentoring women — women understand the struggles, the unique challenges, and the system under which all of us are operating. There’s something unique about that relationship.”

The initial cohort in 2019 included 12 mentor-mentee matches, which has increased to 25 pairings in the just-announced fifth iteration, with specific matches based on shared interest, mentor experience, and mentee need. In Abare’s case, Gibaldi can help her with various entrepreneurship challenges as Abare builds Vircilitation Impact (the name is a play on ‘virtual facilitation’), a consulting business that works with training providers in the business world.

“I was really excited to be matched to her,” Abare said, minutes after meeting Gibaldi for the first time at a WIT mentor-match kickoff event on Nov. 2, adding that she’s excited about Gibaldi’s work with VVM on starting organizations, business acceleration, and more. “I’m definitely going to tap into that experience.”

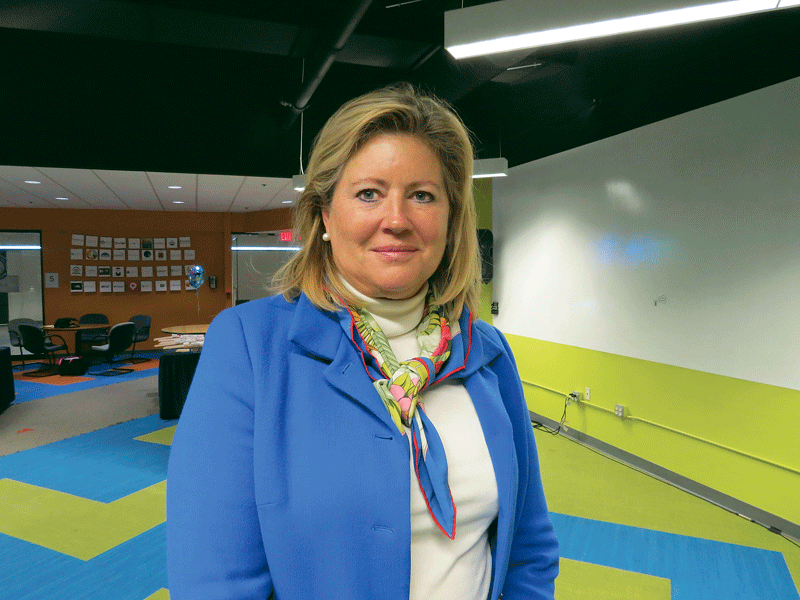

Paulette Piñero, a leadership coach and CEO of Unstoppable Latina, was another mentor on hand at the kickoff to meet her new mentee and network with the group. Her main focus is building a strategic plan for a business, “and then building a brand to attract the right clients, the right opportunities, and the right partners, with a strong brand voice,” as she explained to BusinessWest.

“It’s very refreshing to be able to be vulnerable and talk to other women and realize that you’re not alone, and that we’re all trying to figure it out.”

“I’ve been part of other Valley Venture Mentors programs, and I’m very involved with the work they do — and I do mentoring for entrepreneurs for other programs, like EforAll and the Center for Women & Enterprise,” she said. “So when I had the opportunity to mentor with women and be part of an ecosystem of local entrepreneurs, of course I had to say yes.”

Lighting a Spark

The tagline of WIT is “igniting a women-led economy,” and the program is essentially a community of female innovators and trailblazers with the common goal of supporting other women in their professional and entrepreneurial aspirations. Members include entrepreneurs, professionals, students, educators, and business leaders at all stages of their careers. From the initial meetings of 30 women in 2015, WIT has grown to encompass more than 350 women.

The mentor-match program aims to provide mentoring that helps women navigate their business or career, develop key competencies, and/or grow their professional network. New cohorts begin each fall and run through the spring — typically seven to eight months.

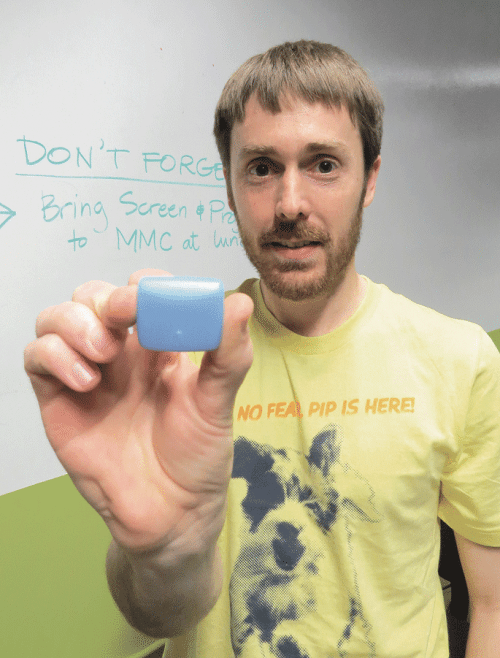

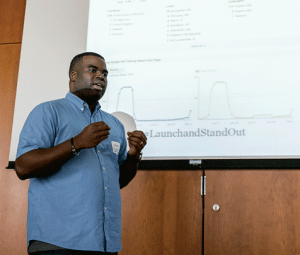

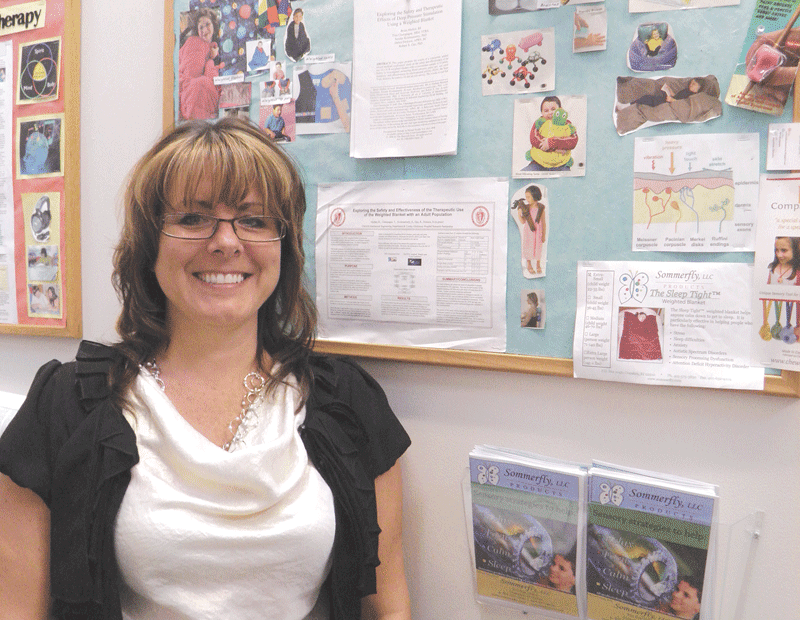

Paulette Piñero says women feel more at ease being vulnerable around other women.

“The program grew over time, and we’ve had a series of other offerings, like networking brunches and educational offerings and workshops,” Gibaldi said. “But over time, we’ve really focused on the mentor-match part of the program.”

WIT leaders spend a month recruiting mentors and mentees. First, the mentors rank several categories — including entrepreneurship, career development, networking, finance, executive presence, and work-life balance — based on their interest and experience.

“I would like to mentor somebody in my biggest background, entrepreneurship,” Gibaldi said a few days before her pairing with Abare was finalized. “I’m also great at networking, so I put that as my second category. The mentees then fill out a form that is basically a mirrored version of that, but they focus on the interests they have and where their biggest mentorship need is. Then we pair them.”

Once the matches are created, WIT gives little specific guidance to the pairs, beyond asking them to meet at least once a month, for at least an hour, in person or virtually — though the interactions can occur as often as they like.

“Once we’ve created the pair, it’s hands-off. There’s not a specific curriculum we follow; it’s based on the needs of the mentee,” Gibaldi said. “We do encourage the pair in the first meeting to create a set of goals and outline what they plan to work on over the next couple of months.”

Abare said the program’s women-mentoring-women model is a valuable one.

“I think, in general, there are unique challenges that are presented to women in our culture, in our society, and when we can understand that context with each other, I think it helps us provide more valuable insight so we can empower each other — because we know, even when it’s not said, some of the struggles and inhibitors, the things that might prevent us from taking a chance or taking a risk or asserting ourselves.”

That latter point is a key one, Abare noted, because women sometimes are not as assertive as men when it comes to stating their value proposition — charging a high-enough fee for their work, for example.

“Research shows that men see themselves as qualified even if they check two boxes,” she added. “Women think they’ve got to have everything checked before they take the initiative.”

Working through that process requires being vulnerable, Piñero added, and women often feel more at ease among their female peers.

“It’s very important to be able to have conversations where we’re vulnerable with other women, so that they can understand what we’re going through, what are some of the obstacles that we face, what are some of the barriers that we face, and hear stories about how we were able to overcome those obstacles so they don’t feel so alone,” she said.

“In my experience, you’re in so many spaces where you feel like you have to be perfect, and there’s this perception that, when you go into entrepreneurship, you should have it all figured out,” she went on. “And it’s very refreshing to be able to be vulnerable and talk to other women and realize that you’re not alone, and that we’re all trying to figure it out.”

Abare agreed. “I think that’s the unique thing about bringing women together in a space. We understand these things from an experiential perspective, so we can empower each other.”

From Mentee to Mentor

Gibaldi said WIT has evolved over time, and even though it’s under the umbrella of VVM, it boasts its own community and serves its own unique need.

“It’s always been received really well, and we have increased the mentor and mentee participation in the program; we have people with a lot of experience with social and intellectual capital participating,” she added. “It goes to show mentors want to give back, and mentees want to get tapped into this network.”

One gratifying element is the number of pairs from previous cohorts who continue to work together, Gibaldi noted. “I think that’s a good reflection on how that curated mentor-match process really works. We take good care pairing people up, and it shows when we have people continue to work together outside the cohort.”

In addition, “another great indicator of success is the number of people who participate as mentees and then return as mentors. We encourage people to go on that journey as well,” she added. “To be able to grow people and transition them from mentees to mentors is very powerful.”

Joseph Bednar can be reached at [email protected]