Saving Graces

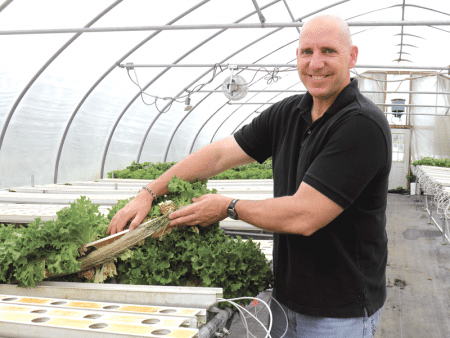

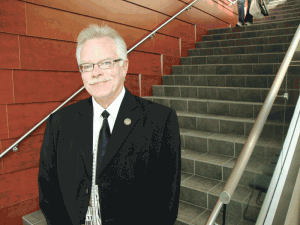

Clarence Smith, owner of Final Touch Barber Shop in Springfield

While outwardly in the business of providing energy, Eversource is making a name for itself in the business of conserving energy as well. Indeed, it has a deep portfolio of initiatives that are slicing energy bills, reducing peak-demand periods, and making a real impact — on both Main Street in Springfield and main streets across the Northeast.

Clarence Smith doesn’t have any trouble remembering when Eversource Energy entered his life — and his business — and helped him see the light, in all kinds of ways.

It was early June 2016. Muhammad Ali had recently passed away, and the boxing legend was on everyone’s mind. Coincidentally enough, he was also on Smith’s wall — the back wall of Final Touch, his barber shop on State Street in Springfield, to be more precise.

A representative of Eversource, the energy company based in Hartford and Boston, with a large presence in Springfield, happened to walk by and see the mural, said Smith, adding that he came in for a closer look, an impromptu visit that led to a wide-ranging discussion and, eventually, some improvement in the numbers on his electric bill.

“He was coming from a meeting at the health clinic across the street … he walked by and said, ‘wow, that’s a beautiful picture,’” Smith recalled. “We talked about Muhammad Ali, I showed him other pictures I had, and I eventually learned that his father used to do some boxing.

“We had a conversation about boxing, and then he said, ‘hey, I work for Eversource. We run a program — how would you like to be part of it?’” Smith went on, finishing the story (sort of) about how he became involved with the utility’s Main Street Energy Efficiency program, which has now impacted businesses on a great many streets in several different communities, and is now focusing on the Indian Orchard section of Springfield.

Through the initiative, business owners save an estimated $600 to $1,000 a year in energy costs through steps that include new and more efficient lighting, occupancy sensors, programmable thermostats, and water-saving devices.

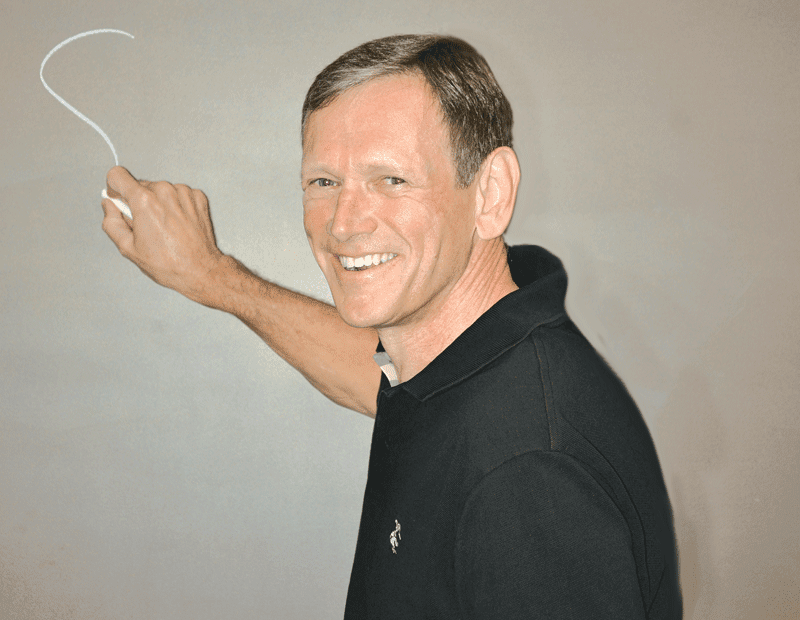

For both Eversource and Massachusetts, Penni McLean-Conner says, conservation is the “first fuel.”

The Main Street initiative is one of many that Eversource has launched with the broad goal of reducing overall energy consumption across the region and across the Northeast, involving communities, neighborhoods, and landmarks ranging from the corner market to Springfield’s Union Station; from Fenway Park to TD Bank Garden.

Others include a small-business program that provides no-interest loans to ventures to undertake similar energy-efficiency projects, often with dramatic results, such as those recorded by the Dakin Humane Society at its facilities in Springfield and Leverett.

There’s also a new focus on solar power, electric-car charging stations, and initiatives to improve storage in many locations — from UMass campuses to Cape Cod — with new technology, including lithium ion batteries and so-called ‘ice batteries’ (more on them later) to better handle peak loads, help alleviate outages, and improve reliability.

And while reducing the amount of energy consumed may seem counterproductive for a utility that sells that commodity, it makes perfect sense, said Penni McLean-Conner, senior vice president and chief customer officer for Eversource, noting that energy conservation is now a state priority and a state mandate.

“We’re at the end of the pipeline, so energy is expensive, and therefore it’s important that we leverage this resource and use it as wisely as possible,” she explained. “And Massachusetts leaders have recognized that conservation is the first fuel, something that was established with the Green Communities Act. And with that, the state has created the regulatory framework and policy framework that has allowed utilities to thrive by investing in energy-efficiency solutions.”

And Eversource has, indeed, invested in a number of these solutions, designed, overall, to help reduce the state’s carbon footprint and, locally, enable utility customers of all sizes and all business sectors to do what Smith did — trim (that’s one of his industry’s terms) his energy consumption.

“Our entire energy-conservation portfolio looks like an asset,” said McLean-Conner, who oversees a team of some 1,200 employees charged, overall, with managing the customer experience and developing ways to improve it. “In a three-year period, our energy-efficiency programs will build the equivalent of a 750-megawatt power plant. That’s powerful, because can you imagine siting a 750-megawatt power plant and getting all the lines up?”

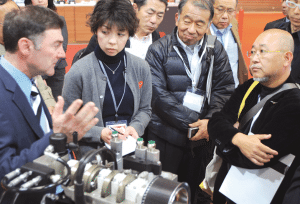

Kim Kiernan, energy efficiency consultant for Eversource, with Charles Brush, owner of Indian Orchard Mills, which has benefited from the utility’s energy-conservation programs.

For this issue and its focus on green energy, BusinessWest takes an in-depth look at Eversource’s Main Street program and its many other initiatives aimed at helping businesses become greener — and save green at the same time.

Current Events

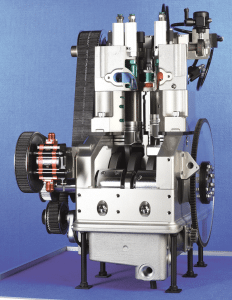

Charles Brush says he’s “a small business that manages space for lots of small businesses.”

That’s an intriguing, but accurate, description of the Indian Orchard Mills, a large mill complex along the Chicopee River that is home to more than 150 businesses. Many of them are artists who don’t use large amounts of electricity, but maybe half are manufacturers that do, especially those that make use of compressors.

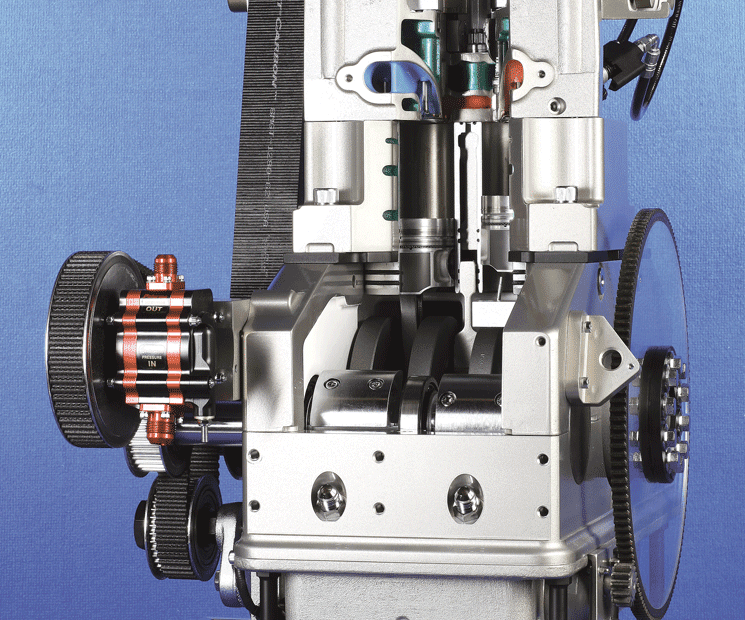

“When machines start up, they create a demand — when machinery kicks on, it creates a higher rate that we pay,” said Brush, who has already had the lighting at the mill changed once through the Main Street program. With another upgrade to LED now in the discussion phase, he’s also hoping to perhaps implement some other electric-efficiency programs regarding machinery and compressors.

“We’re talking about doing what’s known as soft-starting,” he explained, “so that when a compressor comes on, it doesn’t just go from ‘off’ to ‘on,’ which creates that load; it soft-starts the motors so it doesn’t create a spike in demand.”

As noted, Brush is not your typical small business participating in these energy-efficiency programs — his mill complex boasts more than 500,000 square feet of space being put to all kinds of uses. But his issues are in many ways the same as those facing business owners occupying one-tenth, one-hundredth, or even one-thousandth of that footprint, which is about what Smith’s barbershop covers.

Every small-business owner is looking to reduce energy consumption and, therefore, their monthly bill, said Kim Kiernan, energy efficiency consultant for Eversource and manager of the Main Street program, and the utility is committed to helping as many as it can.

“Our plan is to have everyone changed over to LED lighting by 2021,” she said, stating just one of the program’s goals, adding that the Main Street program, which started in Springfield and has been expanded to several other communities, has assisted more than 600 businesses to date.

While all business owners are in the same boat when it comes to energy consumption and the need to reduce it, very large customers do have their own specific issues and challenges, said McLean-Conner, adding that Eversource breaks down the business community into several categories of customers, with usage being the determining factor.

“We don’t look at business customers as one homogeneous group; we realize that our customers have different needs, so we do a lot of segmentation,” she said, adding that very large customers — think colleges and universities, hospitals, the new MGM casino, large manufacturers, and refrigerated warehouses — have their own account executive assigned to them.

But there are also teams assigned to different business sectors comprised of large users — education, healthcare, food-processing plants, and others — with the specific goal of identifying ways to save.

“And each of the solutions for those sectors is different,” she explained, citing the example of higher education and work the utility has done in partnership with the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT).

“When I’m working with education, there’s considerable focus on labs, said McLean-Conner. “Those labs have intense energy needs, so the focus is how we reduce that. MIT was one of the first customers to sign on with us with a strategic energy agreement, a multi-year agreement and a public commitment by MIT and Eversource to reduce energy use over a period of time.

“They have actually increased square footage and reduced overall energy consumption — it’s a tremendous story,” she went on. “But it’s been done through the investment of wise energy-efficiency efforts, whether it’s building envelope and ensuring that the building itself is well-insulated, or heating and ventilation to make sure those systems are increasingly controlled, and lighting, which is obviously huge.”

There are a number of these tremendous stories being written, said both McLean-Conner and Kiernan. Like the one at MIT, they involve the customer partnering with Eversource to achieve stated goals when it comes to reducing energy consumption.

“In a three-year period, our energy-efficiency programs will build the equivalent of a 750-megawatt power plant. That’s powerful, because can you imagine siting a 750-megawatt power plant and getting all the lines up?”

They involve communities — Springfield was among the first, if not the first, city to ink what’s known as a strategic energy agreement with the utility — as well as large customers (UMass Amherst and Yankee Candle in this market are some of the examples cited), and literally thousands of small businesses.

“We try to develop custom solutions for these large organizations,” said McLean-Conner, noting that, at Yankee Candle, for example, the utility worked with the company to showcase various lighting options for franchisees — systems that would not only enhance the customer experience but reduce energy consumption and lower electricity bills.

Watt’s Happening

One of the keys to achieving those goals is making a dent in peak-demand periods, an important development for all commercial consumers, said McLean-Conner, because they pay not only for the energy for they use, but for the peak usage as well.

And recent trends show the peak moving higher, she said, motivating utilities like Eversource to look for innovative solutions, many of them involving a combination of energy conservation and storage of power for use during those peak-demand periods, usually in the middle of the summer when chillers of all sizes are operating at once.

“We want to avoid building resources just for those peak moments — we want to clip those peaks,” she explained, adding that one initiative in that realm is the installation of a large lithium-ion battery-storage system with the goal of reducing peak energy demand on the campus.

Funded through a $1.1 million state grant from the Advancing Commonwealth Energy Storage project, the battery-storage system will provide power that would otherwise have to be purchased from the power grid at premium rates — and it will also provide a research site for clean-energy experts, researchers, and students, said McLean-Conner.

Ice batteries do much the same thing, she noted, adding that there are a few in place across the state. These thermal storage systems produce ice at night when the demand for energy is at its lowest point. When the outside air is hot, the stored ice melts and is used to cool the building with existing air conditioning ducts and fans, but not the compressor, which requires power, she explained, adding that shifting power demand from peak times to non-peak hours is one of the major goals of the energy efficiency programs.

While working to reduce those peak-demand periods through storage initiatives, Eversource continues to work with business owners of all sizes to reduce energy consumption.

With the Main Street program, it works with very small businesses, generally shop owners who are leasing property. Launched in 2015, the program has program has focused on different communities — Pittsfield, Easthampton, Southwick, West Springfield, Ludlow, and Greenfield among them, with Hadley and Amherst next on the schedule — and sections of Springfield each year.

In the City of Homes, work began, appropriately enough, on Main Street, moved to State Street, then to the ‘X,’ and now, as noted, it is focused on Indian Orchard and customers like Charles Brush. There are some 400 small businesses in the Orchard, as it’s called, and Kiernan would like to sign up at least half of them.

That will be a challenge, she noted, because these are partnership efforts, and sometimes, some selling is required to recruit these partners.

Indeed, Kiernan noted that small-business owners, especially those who take part in the Main Street program, are, generally speaking, understandably worried about possible scams and wary of claims of reduction in their energy bills. But once Eversource can convince them to not only listen to the pitch — sometimes it’s difficult to even get a foot in the door — but implement many of the suggested steps, they’ll discover that the savings are real.

The process, with both the small-business initiative and the Main Street program, begins with an assessment by electrical contractors and then development of a detailed plan to reduce consumption. Lighting, specifically a switch to LED lighting, is a big element in these plans, said Kiernan, calling it “low-hanging fruit,” but important fruit, generally able to yield a 40% reduction in cost over what was in the ceiling.

But there are other considerations as well, such as refrigeration, HVAC, motors and compressors, occupancy sensors, programmable thermostats, and others, she went on, adding that measures are implemented without interruption to the business in question.

Eversource provides an incentive to participate, Kiernan added. With the Main Street program, 100% of the project’s cost is covered by the utility, and with the small-business program, 70% of a project’s cost is covered, and the utility will finance the rest over two years, with a zero-interest loan.

Generally, the cost of the loan is more than covered by the savings generated by the measures implemented, she went on, adding that the customer’s bill doesn’t increase through participation. When the loan is paid off, the bill will then decrease by that amount.

In many cases, as noted, all this sounds too good to be true, and utility customers need to be convinced that it isn’t, Kiernan went on, adding that, while it works diligently to do this, often it has help from those who can see first-hand that the benefits are real.

Positively Charged

People like Clarence Smith. He’s become an ambassador of sorts for the Main Street initiative, encouraging many of his business neighbors to take part.

“People don’t believe it until they see it,” he explained, noting that he’s encountered plenty of initial skepticism about the project. “I’m a testament to this program; I’ve seen how it’s worked for us, and if people ask me, I’ll tell them it can work for them, too.”

It all started when someone from Eversource saw his mural of Muhammad Ali and came in for a look and a talk — a talk that led to another of thousands of small steps to reduce energy consumption across the state and the region.

As McLean-Conner noted, conservation has become the first fuel for Eversource, as well as the state, and this mindset is creating a spark — in all kinds of ways.

George O’Brien can be reached at [email protected]