Changing Course

Having a Baby Can — and Often Does — Alter a Woman’s Career Path

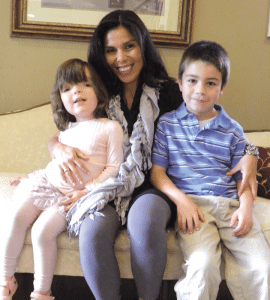

Sylvia Callam says she has no regrets about the time she took off from work to spend with her children.

Sylvia Callam had invested an enormous amount of time and energy into her career, so she said she “thought long and hard” about making the decision to have a child.

“I had worked on Wall Street for eight years,” said the Yale graduate and director of research at Gage Wiley Inc., a brokerage-dealer firm. She planned to take two months of maternity leave, then return to work full-time. And although she doesn’t consider herself overly emotional, Callam felt very conflicted when that time approached.

“When you have a baby, your heart changes,” she said. “I had always been the first one to get to work and the last one to leave. But I was definitely surprised and taken aback by how much I wanted to be with my son.”

So she made the decision to put her family first. “For a few years, my career took a backseat. The motherly love I felt was overwhelming, and I needed some time to make sure that going to work was worth it,” said the Hatfield resident, adding that she only worked two days a week.

When her son, Nathan, turned 3, Callam gave birth to her daughter, Alyssa, who was born with myriad medical issues. Thankfully, her boss was understanding, and although she had returned to work full-time, he allowed her to take six months off.

Today, her children are 7 and 4, and despite working part-time for a period of time, she has made remarkable advances in her career. “I was very fortunate that my boss was willing to be patient,” she said.

Still, Callam believes becoming a mother improved her performance. “It is a real success story even though I have always put my children first; I’m more decisive, more confident, and more resilient than I used to be. I had to learn to do the same amount of work in four hours that used to take me eight, and my boss finds my attitude refreshing,” she said. “I am a much better mom because I work and a much better employee because I am a mother. But it’s all a question of whether a woman has a flexible employer.”

Experts agree.

Iris Newalu, director of Executive Education for Women at Smith College, says women can have both high-power careers and children. “But it’s not easy,” she told BusinessWest, adding that many are able to do so only because of flex time or companies that allow them to work from home. “There is no one formula, and everyone has to figure it out for themselves and decide where to set boundaries.”

Fern Selesnick says there was a myth generated years ago that women could have a family and a job and do it all perfectly.

“The standards are unrealistic, but the myth still exists. And even though employers say they support working mothers, it really is not across the board,” said Selesnick, who works as a professional career coach and trainer at Fern Selesnick Consulting.

As a result, having a child or growing one’s family can pose real challenges for working women intent on climbing the career ladder. Although it can be done, the rate of ascension for those who take a significant amount of time off from their jobs depends on a variety of factors.

“There are competing priorities once a woman becomes a mother,” Selesnick said, adding that concerns change while a woman is pregnant, once she has a baby, and when she decides to return to work. “There is an identity shift. Most women realize after the fact that they can’t give 100% to motherhood and 100% to their job. It requires making adjustments, so they need to figure out how they can do both well and take care of themselves without burning out.”

Experts say women should talk to their supervisors about how a leave of absence will affect their job standing before they become pregnant. “Women need to look at a mixture of practical and emotional issues,” Selesnick said, advising them to begin by reading their employee manual to find out how much maternity leave their company allows.

And when a woman does leave, she should tell her manager, “I hope the door will be open for me to come back,” Newalu said.

Pregnant Pause

Once a woman has a baby, Fern Selesnick says, she realizes she cannot give 100% to her career and 100% to her role as a mother.

A study conducted by Amalia Miller, an associate professor of Economics at the University of Virginia, shows that each year a woman delays having her first child while she is in her 20s and early 30s results in an earnings gain of 9%. This is significant, since other studies show earnings often plateau once a woman becomes a mother.

This results partly from an inability to continue advanced schooling due to the limited number of hours a woman can work due to child-care issues or her desire to be home with her family. Issues mothers discuss with Selesnick include time management, self-esteem, a realistic identity, and career changes or adaptations that must be made, since research confirms that women are still the primary caretakers in families.

Selesnick said the decisions a woman makes and her ability to advance within her company often come down to her supervisor. She cites the cases of clients who were allowed tremendous flexibility. “But some supervisors expect everything to be the same in terms of performance and availability,” she told BusinessWest.

Newalu says women must learn how to negotiate to achieve what they need to be successful as a mother and employee. “Flexibility is key. Once you have a child, you can’t control things; children get sick, have performances at school, and have accidents that require a parent to leave work,” she said.

Attorney Kathy Bernardo was working for the law offices of Bulkley, Richardson and Gelinas in Springfield when she had her first child. And although she continued at the firm, a few years later when she found out she was expecting twins, she made the decision to work part-time.

“I made a conscious decision to get myself off the partnership track — I thought it would be more than I could handle,” she explained. “I knew I couldn’t commit 100% to my firm and my family, and I wanted to be fair to everyone as well as myself.”

When she returned full-time, it took her a year before she re-established her standing within the practice. “It wasn’t easy because I had to prove to them and to myself that I could handle it, and wanted them to have wonderful data to assess,” she said.

Bernardo achieved her goal of becoming a partner, but it took her 10 years instead of seven. “But I got where I wanted to be without sacrificing my family and was actually able to enjoy my children and be there for them in those important early years; babies demand most of your time,” she said.

Today, her children are teenagers, and she has no regrets about her decisions.

“Sometimes people feel that, if they don’t proceed as planned, they will lose their opportunity,” she said. “But I was fortunate to be somewhere where I could have that dialogue with my employer.”

Experts agree that a woman should have a frank discussion with her supervisor, manager, or someone in the company’s human-resources department before she leaves her job. They advise women to maintain relationships at work while on extended maternity leave, which has personal and professional benefits.

“It’s important for a woman’s self-esteem and confidence to feel that she still has a hand in her career and her work identity isn’t gone,” Selesnick said.

Other safeguards can help her to remain marketable. Selesnick recommends working part-time or doing volunteer work in an area that correlates to one’s career so there is not a large gap in a résumé.

Women also have a responsibility to stay current in their fields, Newalu said, adding it is especially important for those who work in information technology or other areas where change occurs rapidly.

Fair Exchange

Tricia Parolo’s career began in 1997, when she became an intern at MassMutual. In 2000, she achieved full-time status and held a variety of positions within the company until 2007, when she left to become a full-time mother.

“My husband and I had planned for it for two years; I took a leap of faith because I had no idea what to expect and what it meant to be a stay-at-home mom,” she said, adding that she had her second daughter shortly afterwards and soon discovered that working in an office seemed easier and less stressful than raising babies.

“I found it was really, really hard being at home,” Parolo said, adding that other people perceived her differently once she lost her professional identity.

She retained the part-time retail job she’d had while she was at MassMutual, but sometimes felt jealous of her husband when he left for work. “I was constantly torn about my decision.”

In 2010, a co-worker who had risen to a management position contacted her and asked if she wanted to work 20 hours a week. Parolo’s former colleague allowed her to work at home from 7 p.m. to midnight, although she did have to go into the office for four hours one day a week.

The following year, when her youngest daughter was 2, Parolo returned full-time and found she had to prove herself all over again. “I worked really, really hard to make up the gap,” she said.

But she has no regrets. “I had the best of both worlds. I was able to stay home with my two little babies and pick up where I left off,” she told BusinessWest.

Newalu says the top companies in the country are willing to invest in a woman’s career and make accommodations if she has a good track record, has been an excellent employee, and has established good relationships. “Talent is very expensive, and companies do not want to keep training new people; they want good employees back.”

However, as Parolo and Bernardo discovered, no one should expect to take up to a year off without consequences.

“It is unrealistic to think that you can slip right back into the position you had — a woman will probably be put where she is needed,” Newalu said. “The situation is the same for anyone who takes time off; you lose seniority, and the people who have stayed on the job have more understanding of the current situation.”

Women who cannot return to their previous position or are unhappy about what they are offered may want to seek employment at another company. However, when they do return to work — whether it is with their previous employer or a new one — they should know what they need and be willing to talk about these needs, even though it may be uncomfortable.

“Research shows that women don’t tend to be good negotiators. It’s a learned skill,” Newalu said, explaining that they can take a course, read books on the subject, or get a coach to teach them how to leverage their talent.

“Early in my own career, I did what I was told, but as I got more experienced, I learned to ask for what I needed,” she said. “You have to be willing to step outside your comfort zone. If you ask for what you need in the right way, you often get it. It can’t hurt to ask, and if you don’t have an open-door situation, you have to define how you will re-enter the workforce.”

Prior to becoming a mother, Selesnick held positions in management where she was required to be available at all times. She took a few years off when she had her daughter, but continued her part-time job as a writer. “It was a cut in income, but it allowed me to be the mother I wanted to be,” she said. “If I had taken a corporate management position, I couldn’t have been a mother in the way I wanted.”

When she did return to full-time work, she chose a much easier position at a nonprofit agency with a set schedule that didn’t include night or weekend hours. “Plus, my boss let me bring my daughter to work if it was necessary. Life was much simpler.”

Back to Business

As children grow, women often find that juggling roles becomes easier. “Women need to know that the demands of motherhood decrease and the time will come when you have complete flexibility again,” Selesnick said.

In fact, taking time off can be simply viewed as a detour on a career path.

“I am so glad that I persevered,” Callam said, “even in the lowest of times.”