Dead Last

The Roots of Hampden County’s Health Problems Run Deep

Dr. Andrew Balder says the socioeconomic data behind Hampden County’s health ranking is impossible to ignore.

Is Hampden County the least-healthy county in Massachusetts?

Well, the numbers don’t lie, but they also point to factors that run well beyond — and much deeper than — access to quality care.

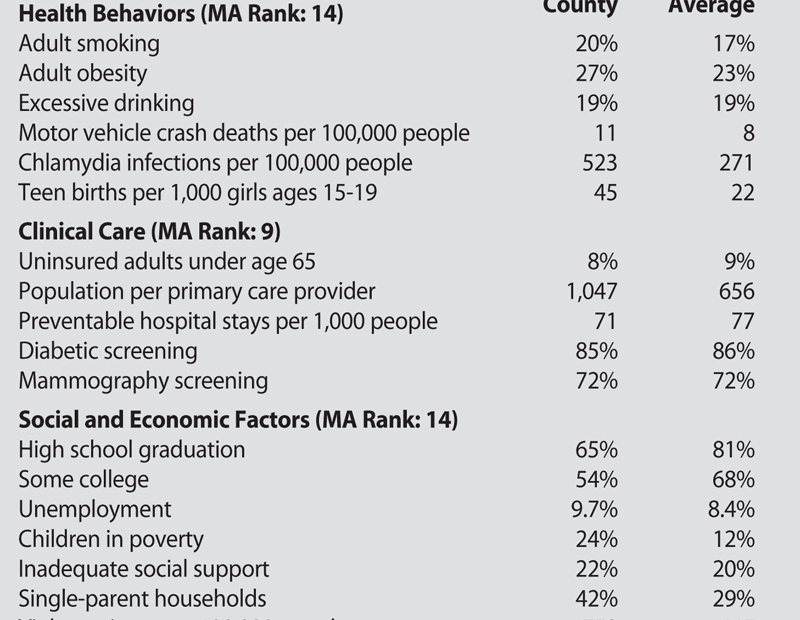

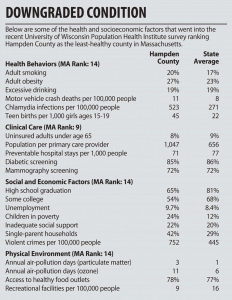

That’s the message conveyed in a recent survey of every U.S. county. The 2011 County Health Rankings — produced for the second straight year by the University of Wisconsin Population Health Institute and the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation — ranks Hampden County 14th among 14 counties in Massachusetts in overall health.

Initially, that might seem like a slap in the face to a region that’s home to many high-quality hospitals and other health care providers, but a closer look reveals issues that can’t be solved by the medical establishment.

“You can always question the data, but there’s reality behind it,” said Dr. Andrew Balder, attending physician at Baystate Mason Square Neighborhood Health Center and medical director of the Boston Medical Center HealthNet Plan.

He noted that socioeconomic factors played heavily into the rankings, putting many urban centers — which tend to be home to significant pockets of poverty — at an immediate disadvantage (Suffolk County, containing Boston, ranked 13th). The survey gave 10% of its weight to a county’s physical environment, 20% to clinical care, 30% to health behaviors, and 40% to social and economic demographics.

“It does take a village,” Balder said. “This is a direct reflection of Hampden County, of the difficulties of a county dominated by one poor city — Springfield — and a second, smaller, poorer city, Holyoke.”

Dr. Franklin Robinson, executive director of Baystate Health’s Partners for a Healthier Community, agreed. “If you look at the urban core on this county — Springfield and Holyoke — those two centers probably account for the majority of the county’s bad report, because these are problems that really concentrate in urban centers,” he said.

“That tells me this county is really healthier than we suspect, but the urban centers are that much more dramatically challenged, and that brings down the entire report,” he added. “It also signals that these are population-level problems that require much more than tinkering.”

The survey ranks Hampden County well below the top duo of Nantucket and Dukes counties, which represent the islands south of Cape Cod, but that’s not a useful comparison, said Dr. Garry Bombardier, medical director of the Work Connection at Holyoke Medical Center.

“I know everyone wants to compare us to Dukes County, but that’s a very different part of the world,” he said. “It’s more helpful to take a look and compare us to the next county over — Hampshire County, which turned out to be fifth.”

“I know everyone wants to compare us to Dukes County, but that’s a very different part of the world,” he said. “It’s more helpful to take a look and compare us to the next county over — Hampshire County, which turned out to be fifth.”

And some of the comparisons are striking. The premature death figure — which calculates total years of life lost before age 75 — is 44% higher in Hampden County than in its northern neighbor, owing partly, of course, to the much higher rate of violent death in young people endemic to many cities like Springfield.

On the other hand, Bombardier said, “low birth weight in babies is very often an indirect measure of health care, nutrition, and economic status.” On that count, 8.6% of Hampden County babies are born underweight, as opposed to 6.4% in Hampshire County.

He cited other disparities between the two Pioneer Valley counties — a teenage birth rate of 4.5% in Hampden County and 0.7% in Hampshire County; high-school graduation rate, 65% and 85%; unemployment, 9.7% and 6.6%; single-parent households, 42% and 25%; children in poverty, 24% to 10%; and a violent-crime rate three times higher in Hampden County than in Hampshire County, to name a few.

“Again, this is taking a look at the fiber of our society, and it has to do with education, with social and economic factors, do you have jobs, things like that,” Bombardier said. “It’s a very big difference, and we should really be paying attention to it.”

The authors of the study recognize that they’re casting a wide net. “The rankings really show us with solid data that there is a lot more to health than health care,” said Dr. Patrick Remington, the project’s director, when the report was released earlier in the spring. “Where we live, learn, work, and play affect our health.”

Many Miles to Go

The report comes as no surprise to Mark Fulco, vice president for Strategy and Marketing for the Sisters of Providence Health System, who conducts a detailed community-needs assessment as part of the system’s overall planning and resource allocation.

The Wisconsin study “really deals with a lot of those issues,” he explained. “One of the things we look at is a community needs score; we look at each ZIP code and come up with a score from 1 to 5, with 5 representing the highest needs, based on factors like poverty rate, unemployment, and insurance coverage.”

Springfield, Holyoke, and parts of Chicopee all score very high on that scale, Fulco noted, adding that populations in this range are more likely to wind up in the hospital for conditions, like pneumonia and congestive heart failure, that people in communities with better socioeconomic scores are more likely to handle through primary care.

“If poverty influences health to a significant degree, then the [last-place] ranking is appropriate,” Balder said. “It’s part of the underlying environment that creates an unhealthy physical and social environment. It makes individual healthy behaviors more difficult to attain, and when you make the barriers higher and stack the decks, it becomes harder and harder to act on healthy decisions.”

Fulco cited a survey conducted by the Mass. Executive Office of Health and Human Services, which asked residents to rate their own health, and 21% of Springfield residents rated it ‘fair’ or ‘poor’; the state average was just over 12%.

“No wonder the report ends up where it does,” Fulco said, also citing asthma rates, tobacco use, inadequate prenatal care, and other factors in which Hampden County posts numbers nearly double the state average. “The magnitude of the problem is substantial. We’ve got a societal challenge, and it’s important to put public resources toward addressing these needs.”

As a health system, Fulco said SPHS is doing exactly that, from its mental-health programs run through Providence Behavioral Health Hospital to its participation in REACH programs in area schools; from its community health screenings to its Vietnamese Health Project that strives to reduce barriers to health care for the city’s Vietnamese population. “We know we are here to serve our community, and our services need to reflect that,” he said.

Robinson mentioned some community-based projects aimed at reversing some of the underlying factors highlighted in the report.

“The good news is that, in our local communities, there have been some neighborhood groups working together to affect some of these indicators,” he said, citing projects like the Mason Square Health Task Force, the North End Campus Coalition, and others that emphasize economic development alongside social needs.

“We’re beginning to look at the human social issues affecting residents,” he said. “In some of our most challenging neighborhoods, whole collections of people are trying to figure out how we can improve quality of life and the economic experience of our communities and, consequently, the health and well-being of the people who live there.

“It’s a public-health situation; it’s not just a health care problem,” he added. “To change our county’s health status, people need jobs, and they need housing. Essential to good health is the ability of a family to live in an economically self-sufficient manner.”

Some of the long-term statistics have been distressingly consistent, Robinson noted. For instance, infant mortality among African-Americans in the region is about three times that of white infants — the same gap that was present 30 years ago. “That’s a hard indicator that we haven’t been able to effectively organize our resources. We have not made an impact on changing that rate.”

And that’s just one of many stubborn trends, he said. “That’s what makes this so daunting — there isn’t a simple solution out there; there isn’t just one way to do it. How do we, as a community, work to achieve collective impact?”

A Call to Action

Like the others who spoke to BusinessWest, Balder believes the effort is worth it.

“Just because a community is poor doesn’t mean people have to be unhealthy,” he said. “A community can become healthier even though it’s poor. You can throw your hands up and be defeated, or keep working.”

The report’s authors claim that several communities across the U.S. have begun to take action in response to last year’s study, such as passing smoke-free laws, boosting educational opportunities for young children, and pushing for healthier grocery stores and farmer’s markets. But those who work with public-health issues in Hampden County have long been aware of the region’s needs.

“It’s more than the medical delivery system,” Bombardier said. “We’re definitely seeing more people dying younger and more low-birth-weight babies, who require lots more care, and many of them require special education later in life to get them back up to where they belong. We can see the results of poverty, of not having educated people, of not having enough primary-care providers. It’s an overall problem with our community.”

Dr. Risa Lavizzo-Mourey, CEO of the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation, noted that “it’s hard to lead a healthy life if you don’t live in a healthy community.” But the inverse is also true — communities don’t get healthy unless their residents start living healthy lives.

And despite the well-documented barriers, “we have a very bright community with some very active people,” Bombardier said. “My hope is that this will spur people to look at what we can do to make a difference.”

Joseph Bednar can be reached at [email protected]