Down to a Science

UMass Wants to Raise Its Status Among Research Institutions

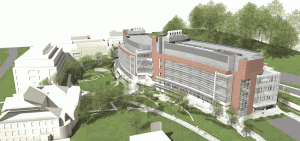

It’s called the New Laboratory Science Building, or NLSB, a $156 million, state-of-the-art facility now taking shape on the UMass Amherst campus. It’s part of a larger, nearly $300 million initiative, which also includes the Integrated Science Building opened in late 2009, to create a life sciences ‘precinct’ or ‘community’ on the campus that is being designed to greatly increase research capacity and facilitate collaborative efforts among science departments. The new facilities are expected to play a lead role in helping the university meet its stated goal of doubling its overall research volume by 2014 and climb within the ranks of the nation’s leading research institutions.Karen Hayes says that, when it comes to word associations, many possible answers come to mind when one mentions UMass Amherst.

A beautiful suburban campus is one of them, said Hayes, who works as director of Strategic Communications and Outreach for the university, while strong undergraduate programs might be another, and service to the Commonwealth could be a third. One phrase you probably won’t hear is ‘major research institution,’ or words to that effect, she continued, adding that, while it’s certainly not written down anywhere, it’s part of her job description to change that equation.

Part of the strategy for doing so is simply telling the university’s story better and with a louder voice, she said, noting that there are currently a number of intriguing research initiatives underway on the campus, such as one she’s written about herself involving work that sequenced the first full genome of a female Hereford cow.

“We need to get our name out in the public,” she said. “When the Boston Globe or the New York Times or the national publications talk about discoveries in science, we have to be there; our name has to be out there as much as Harvard, Ohio State, MIT, the University of Michigan, or any of the other research powerhouses.”

For that to happen, the university needs to have more for those publications and others to write about, Hayes continued, and the $156 million New Laboratory Science Building, or NLSB, as it’s called, now taking shape on the campus should certainly provide a real boost for those efforts. The 310,000-square-foot facility will provide not only the physical space for additional research initiatives, but also a collaborative environment in which scientists across a number of different fields can more easily work together on projects, she said.

Mike Malone, the university’s vice chancellor of Research Engagement, agreed. He told BusinessWest that the NLSB will play a lead role in helping the university meet its ambitious goal, set in 2009, of doubling its level of federally funded research within five years.

“The NLSB will greatly increase our capacity for doing research,” he explained. “It will give us more equipment, more people, and more modern laboratories. Most importantly, though, it will bring people together in collaborative efforts.”

The NLSB is actually the second phase of a nearly $300 million initiative to create what many are calling a life sciences ‘precinct,’ or ‘community’ on the Amherst campus. The first was the university’s $114.5 million Integrated Science Building, which brings classrooms and labs for the life, chemical, and physical sciences together in one building, thus improving the prospects for collaboration.

Steve Goodwin says the Integrated Science Building brings people in several different disciplines together to effectively solve problems.

For this issue, BusinessWest takes an indepth look at UMass Amherst’s emerging life-sciences precinct, how it will play a lead role in ongoing efforts to move the university to another level when it comes to research institutions, and also how the process of moving up in the ranks requires more than building more lab space.

Good Chemistry

Tom Whelan, a chemistry professor at the university, told BusinessWest that it couldn’t, or shouldn’t, print the words used by many of his students when they first glimpsed the new laboratory facilities in the ISB. “Holy sh—— was the most common refrain,” he said, not actually using the offending word in question.

That and other colorful phrases were needed to adequately put into the perspective the difference between what the students had for facilities in their former home at Goessmann Lab and what they now enjoyed at the ISB, said Whelan, noting that everything in the new science building is spacious and state-of-the-art.

“It’s great space — it’s a better learning environment, and it’s already changing the way we do things,” he said, adding that, while the ISB is bigger, it allows educators to work smaller in terms of attention to individual students. Meanwhile, it improves the flow of communication between departments that were in separate buildings and brings more opportunities for collaboration.

Goodwin agreed. As he led BusinessWest on a tour of the ISB, he said the building’s design encourages interaction among students and faculty, certainly much more so than was possible when departments were scattered around the campus in buildings as much as a century old and with outdated facilities.

He said the underlying concept for the building actually started to take shape 10 to 15 years ago, when those in the field noticed that the way science was done was changing.

“Therefore, we concluded that the way we train people should change as well,” he explained. “We realized that bringing people from multiple disciplines together to solve problems is the way things move forward. So this building was built on a teaching concept that said, ‘OK, we want to teach in the same way; we want to take the people who are taking introductory chemistry and physics and biology, bring them together in the same building, and give them opportunities to interact.’

“The exciting thing is that, over time, that notion has become more and more defined,” he continued, citing a new program initiated this fall called iCONS, short for Integrated Concentrations in the Sciences, where faculty members across several fields try to bring multiple disciplines together to solve problems.

This notion of bringing people together to work in collaboration is also at the heart of the NLSB, said Malone, adding that the facility is being designed with the goal of promoting collaboration, while also greatly upgrading the facilities in which people are performing critical work.

“Now, faculty members are typically located in individual buildings or parts of buildings that are assigned to their particular departments,” he explained. “And that makes it not impossible, but a little more difficult for their students and they themselves to get together. In this new facility, they’ll be living and working in the same environment.

“And it’s a great upgrade for our facilities,” he continued. “We have quite a backlog of deferred maintenance on campus, and this will put people who are, in many cases, from labs that aren’t state-of-the-art into a state-of-the-art facility.”

Roughly half the NLSB will be finished labs, and the rest will be shelf space, said Malone, noting that this will provide the university with cost-effective room to grow for the future.

A New Culture

And that room will eventually be needed if the university is to meet that stated goal for doubling its research volume by 2014, and then continuing a steady pace of growth. For the fiscal year that ended last June 30, the university logged $170 million in research projects from all sources, a number aided by large amounts of federal stimulus money, compared to $137.5 million for the prior year.

For fiscal 2011, the first-quarter numbers are tracking just ahead of the ’09 figures, which was expected as the level of stimulus funding drops, he continued, adding that the university wants to reach or exceed $270 million by 2014.

With that goal in mind, Malone has created a new Office of Research Development, which will work to identify funding sources and assist individuals and departments with putting proposals together.

The life sciences have been identified as a large growth area for the university, said Malone, noting that, at present, 45% of the federal funding awarded to the school is from the National Science Foundation.

“We have room to grow in areas supported by the National Institutes of Health, and some of that growth will be enabled by a collaboration with people at our medical school,” he explained. “They just got what’s called a Clinical and Translational Science Award from the NIH to support projects that link basic science with the practice of medicine — translating the results from the benchtop to the bedside. This translational area is a good one for us in terms of growth.”

And as research volume grows, and the university escalates its efforts to tell those stories regionally and nationally, UMass will make headway in its ongoing efforts to become more well-known as one of those aforementioned research powerhouses, said Hayes, noting that the story-telling process is an important, sometimes overlooked part of the equation.

“If we want to build our image with the general public and other constituencies, we need to be able to tell our story well,” she told BusinessWest. “Telling your science story well is something we haven’t done, and it’s a challenge. How can you connect the average person who doesn’t know a lot about science to what going’s on here in a way that helps them understand what’s in it for them? That’s what we have to do.”

The new science facilities on the campus will help the university raise its stature in a number of ways, said Hayes, adding that the ISB is a powerful tool in attracting students and faculty to the school.

“It’s a springboard to talk about research on campus and students’ opportunities there,” she said, adding quickly that the new facilities are all about creating more of these opportunites. “In the past, if you were a student who wanted to get research experience on campus, you had to be bold, you had to approach a faculty member, engage them directly, and take the initiative. With these new facilities and new programs that we have to connect students to research experiences, it is so much easier for them to seize opportunities.”

The Bottom Line

The NLSB is slated to open in the summer or fall of 2012. In time, and probably not much it, the facility is expected to generate those collaborations that Malone and Goodwin talked about, as well the critical momentum the university will need to take its name and reputation within the world of science to a higher level.

And perhaps sometime soon, when people do play word-association games with UMass Amherst, the phrase ‘major research institution’ will be appropriate, and widely used, vocabulary.

George O’Brien can be reached at [email protected]