Driving Force for Change

Springfield’s New Police Commissioner Charts a Course

John Barbieri acknowledged that his analogy wasn’t perfect, but believed it worked on a number of levels, so he went with it.

John Barbieri acknowledged that his analogy wasn’t perfect, but believed it worked on a number of levels, so he went with it.

He was talking about law-enforcement personnel and why many people don’t understand why they can’t prevent crime, or criticize them for not doing so. And he drew a comparison to getting a bad diagnosis from one’s doctor.

“For a community to expect the police to resolve crime in a city is like going to your doctor and being mad at him because you have cancer,” said Barbieri, a deputy chief who will become Springfield’s police commissioner next month. “If the doctor could go back 20 years and take the cigarette out of your hand or stop you from working at the asbestos factory, that would be one thing. Don’t be upset with him because you have cancer; be upset with him if he doesn’t treat it properly.

“I can’t go back 20 years and give the person who broke into your car an educational opportunity or parental discipline,” he went on. “The best I can possibly do is look at the trends and patterns from when such break-ins occur, be responsive and try to have police in that area, make an arrest whenever possible, and work with area residents and educate them about what’s going on in their neighborhood.”

If a community wants to make a serious dent in crime, there must be what he called a “holistic response” to the matter, and a police department will certainly play a key role in that, he said, adding that police must work in collaboration with neighborhood residents, other social agencies, the school department, and other players.

Indeed, collaboration has been the word heard most often in the many media interviews, neighborhood meetings, and other gatherings at which Barbieri has spoken or taken questions since he was named commissioner on March 19.

And it will continue to be heard in the weeks, months, and years to come, because it is the one-word thrust of Barbieri’s philosophy regarding public-safety initiatives and how to make them more effective.

Collaboration between police, the public, and neighborhood groups lies at the heart of the C3 (Counter Criminal Continuum) Policing program in the city’s North End, a multi-faceted initiative aimed at stemming gang-related crime, which Barbieri has co-led, and for which he and other organizers were named Difference Makers by BusinessWest in 2013.

Barbieri wants to expand that specific program to Mason Square, the South End, and Forest Park, but he wants the key ingredients in its success formula — cooperation and information from neighborhood residents — to become a city-wide phenomenon.

“The goal is to go into those neighborhoods and work with the residents to teach them that the department does care, legitimize our services to them, and show them we can be responsive,” he continued. “And then educate them with regard to their responsibilities with preventing crime in their neighborhoods and being our eyes and ears.”

And while working to inspire residents to take a more active role in public-safety efforts, Barbieri has a number of other goals and objectives — everything from making more effective use of available resources to improvements in crime analysis, to making sure the department is ready if and when a casino opens in the South End.

In a broad-ranging interview with BusinessWest, he addressed those issues and many others, and in the course of doing so, put that term ‘collaboration’ to early and repeated use.

Chief Concerns

The office at police headquarters that Barbieri will soon be vacating in favor of the commissioner’s space has an eclectic array of photos on the walls, everything from assorted views of his prized 1966 Chevy Impala — “driving it keeps me sane” — to an image of the World Trade Center the moment the second plane struck the south tower. He said he hung it there so he could point to it whenever someone says a major act of terrorism can’t happen in a city like Springfield.

There’s also a shot of him in a cruiser taken a few months after he joined the force in 1988, one of several times the city was beset with fiscal problems and the police budget was stretched thin — as the photo made clear.

“We didn’t have enough money to paint the cruisers black and white,” he said in noting why the car he was sitting in was all white (it came that way), and also why it looked beat up. “The car was in such disrepair that you had to leave it running at all times. It had a bad battery, so you ran it all night; if you shut it off, it wouldn’t restart, and you’d have to call a tow truck and get a jump.”

Several years later, during the Clinton presidency and a period of heightened federal assistance for law-enforcement efforts, things were much different. Springfield’s force numbered roughly 700 officers, nearly double the current number, community policing was in vogue, and the police could effectively “smother” crime in many ways and many places, said Barbieri, by effectively deploying all that manpower.

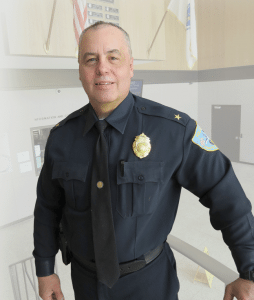

John Barbieri has a number of goals and objectives for his department, including an expansion of the C3 Policing program into three additional neighborhoods.

Talk of inspiring more collaborative efforts has dominated what Barbieri called the “whirlwind tour” he’s been on since he prevailed over two other deputy chiefs in the search for the successor to the retiring William Fitchet.

That tour has included interviews with many local media outlets, community meetings, and the release of his five “priority objectives” for the department and his administration:

• Initiate a movement toward a proactive, patrol-centered department ideology;

• Deliver improved response times;

• Create increased levels of service through clearer lines of delegation of authority and responsibility for line supervisors;

• Build relationships with stakeholders for collaborative problem-solving, enhanced communications, and unified effort; and

• Develop and implement measurement and feedback processes to modify and enhance operations as required regarding calls for service.

Barbieri borrowed the term ‘listening tour’ to describe the six weeks or so since he’s been named the new commissioner, and said it will continue for the next several months, and involve meetings and briefings with the Chamber of Commerce, the City Council and its various subcommittees, the press, concerned-citizens groups, and many other constituencies.

“Hopefully during the listening tour there will be educational opportunities for both of us,” he said. “I want and need to know what some of the concerns of the community are, although I’d like to think I’m fairly well plugged in. And the other part is educating people about this department; there are people out there who still think we have 700 officers and community policing and that we’re going to be able to focus on every small aspect of their concerns. We’ll work with them with regard to prioritization, and I have to work on attaining maximum efficiency here.”

It’s been a relatively quick ride to the top for Barbieri, who joined the force in 1988 after serving as a special police officer for Baystate Medical Center and later as a supervisor there.

Seemingly from the start, his work on the force has involved gangs and gang-related violence. Indeed, one of his first assignments was with the City Uniform Anti-gang Patrol, and after working on a patrol that focused on the city’s schools, whereby he became familiar with many at-risk youths, he was one of the city’s first two gang-intelligence officers.

He was named sergeant in 1995, lieutenant in 2001, captain in 2005, and deputy chief in 2009. In that latest assignment, he had a number of responsibilities, including supervision of the uniform division, the Police Academy, the Street Crimes unit, and anti-gang deployments, including the C3 initiative.

That work in the North End, which he remains involved with, has garnered local and national press, including a segment on 60 Minutes, with Barbieri sharing the spotlight with State Police Officers Michael Cutone and Tom Sarrouf, who drew inspiration for their counter-insurgency tactics from their experiences serving with the Special Forces in Iraq and Afghanistan.

That press has inspired a number of cities to explore creating similar initiatives, said Barbieri, adding that he was recently in Michigan, consulting with state police there on plans to create programs in Detroit, Lansing, Flint, and other cities.

“They’re running into a lot of the same problems in those cities that we ran into here — gang activity and economically impacted cities,” he explained. “And they have several cities that don’t have the financial wherewithal to increase their police departments. So they reached out to us because we have a plan and it’s working.”

Arresting Developments

Overall, the C3 program has been hailed as a major success — crime is down in a number of categories — and the initiative has shown what can happen when the residents of a neighborhood take an active role in making it safer by reporting crimes and providing police with information that could prevent more of them.

As an example, he pointed to a recent shooting on Osgood Street that remains under investigation. Thanks to shot-spotter technology, police were on the scene within a minute, and have received a number of leads from witnesses.

“The level of cooperation we get now down there is just unprecedented,” he said. “We got a number of tips and calls, and we continue to get tips and calls since the shooting occurred. That just didn’t happen before C3 Policing.”

It’s happening now, he said, because those involved in the program have been able to convince residents of the North End that there is a direct connection between this higher level of cooperation and improved quality of life. And this is something that has to happen in other neighborhoods, he said, adding that an obvious key is the simple act of reporting crimes.

“Statistics just tell you about reported crime,” he noted. “And if you look at the worst neighborhoods, where we have the shootings, the drug dealing, and other crimes that makes the newspapers and television, it’s all the little things, the lawlessness in that neighborhood — it’s permissive for all this to occur. And in those neighborhoods, they don’t report crime because they’re afraid, they’re inured, and they’re apathetic.”

The risk to doing all this is that there will be reported crime, something that might create apprehension among those who watch crime statistics or drive Springfield higher on those infamous lists of the most dangerous places to live, he went on, but when crimes are reported, police departments have a better chance of preventing more of them down the road.

Looking forward and acting on the assumption that there won’t be significant, if any, additions to the force in terms of personnel, Barbieri said one of his priorities is to review departmental procedures and initiatives with the goal of ensuring that people and resources are being used in the most efficient manner possible.

“The goal is to take a baseline snapshot of what we do, look at where we want to be, and analytically look at a transition method to get us there,” he said. “We need a projected plan and timeline — and I have the basis of that on paper and in my head — and get a management team in here, because as smart as I’d like to think I am, it’s much smarter to take the experience and intelligence of eight or nine people and put them together to come up with a well-balanced plan.

“The objective is to make us the most efficient department possible with the number of officers we have,” he went on. “There may be a time when I’ll go to the mayor for more police officers, but I’m not there yet.”

And those aforementioned partners that Barbieri listed, especially city residents, can play a role in making the department more efficient through the information they provide.

“In this modern era, what we need is for people to report crime; we need neighborhood residents to get involved and be the eyes and ears of the police,” he told BusinessWest. “And we need to look at that reported crime and put officers where it’s occurring. It’s less about free travel time for police officers for discretionary response, and more about directed patrol time, because there are so many things going on above and beyond what the sector officers may know from their own experience. Neighborhood residents and our computer experts here can predict trends and patterns, and we need to put officers where the dots are.”

Elaborating, Barbieri said another of his goals is to improve crime-analysis efforts, something Boston has been doing, in an effort to both stem crime and more efficiently utilize available resources.

“Instead of catching on to a series of breaks into homes after there have been 30 breaks, and have eight detectives follow up in hopes of catching somebody,” he said, “my hope is to catch on to a series of breaks after three or four them, have uniformed patrol officers patrol more heavily in those neighborhoods in an effort to apprehend that person, but, more importantly, to deter them.”

Looking further ahead, and toward the elephant in the room, the $800 million MGM Springfield gaming and entertainment complex planned for the South End, Barbieri said it will present new and different kinds of challenge for his department.

There are still some hurdles to clear before it becomes reality — especially a referendum question that will soon be in the hands of the Supreme Judicial Court — and it will be at least three years before a casino opens its doors, but Barbieri said the city, and his force, must aggressively move forward with the assignment of being ready.

“We have to plan, plan, plan, plan — that’s the biggest thing,” he said, adding that there will be visits to a number of cities that have casinos to observe, ask questions, and learn. “And once the details start to emerge as to just what we’re looking at, we have to start planning immediately. And then you have to plan to adjust your plan once it starts.”

Off-the-cuff Remarks

Thinking back on those days when Springfield had 700 police offers and could easily afford to paint its cruisers black and white, Barbieri said everyone knew that those conditions wouldn’t last forever — and they didn’t.

“We made the most of it while we had it, though,” he said, adding that the force has adjusted to the new reality, and it will continue to do so in the years to come. Part of that adjustment is stressing that holistic approach to improving public safety and then making it happen.

And this comes back to that notion of collaboration — a word you’ll keep hearing from the new police commissioner long after his listening tour is over.

George O’Brien can be reached at [email protected]