Energy Fields

WMECO Projects Shine Light on Solar Power’s Potential

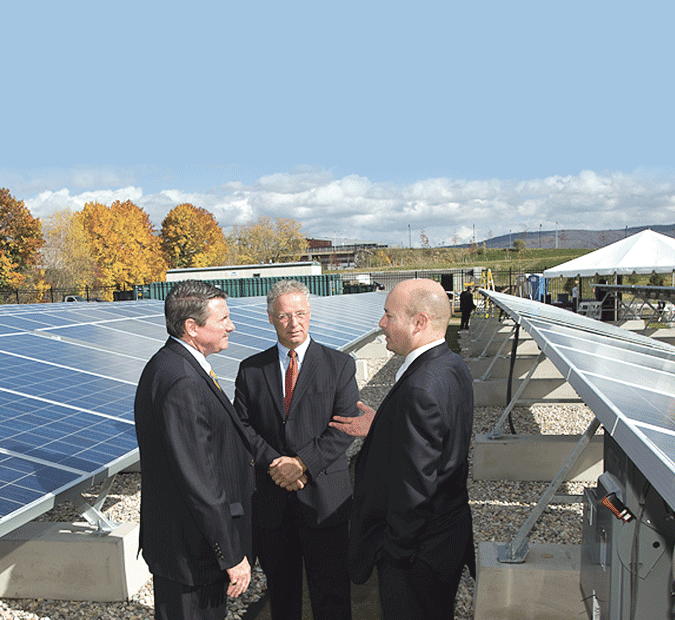

From left, WMECO President and CEO Peter J. Clarke;Project Manager William Blanchard; and Director of Business Development Carl Frattini stand in the field of solar panels at the company’s Silver Lake solar-power facility in Pittsfield.

Last fall, Western Mass. Electric Co. embarked upon a difficult and ambitious project.

In October, the Springfield-based utility completed the largest solar-energy facility in New England at the William Stanley Business Park on Silver Lake Boulevard in Pittsfield. The photovoltaic system contains 6,500 low-profile solar panels and produces 1.8 megawatts of electricity, or enough to power about 300 homes. And in January, the company announced plans to build an even larger solar-energy facility on a capped landfill on Cottage Street in Springfield. When it is complete, it will contain more than 15,000 panels that will produce up to 4.2 megawatts of solar energy, or enough to power about 700 homes.

Several objectives led WMECO to this huge undertaking, including the question of economy of scale. Not only did the company want to be a leader in the utility industry in terms of solar power, it also wanted to discover whether large installations would prove more cost-effective to build than smaller ones.

“Solar power is one of the more expensive types of green technology,” said Carl Frattini, director of business development for Northeast Utilities. “The price is declining quickly, but it costs considerably more than wind power. It is so new that it has been a riddle to solve how to make it less expensive for the customer. Our bet with these projects was that we could build them for less than in the past. We also wanted to act as a catalyst to the development of solar infrastructure because we are trying to help develop the market. We are very pleased with the progress that has been made.”

The construction of both of WMECO’s solar power facilities has involved a multitude of environmental, business, energy, and technical challenges. “We have developed a new type of project in an area where there was very little activity,” said Frattini. “We did it with a considerable amount of collaboration with the solar industry, the state’s indigeneous technical resources, the administrations and local communities.

“The only way these projects can happen is through an aligning of interests,” he continued. “It is exciting work and really gratifying to see it come together.”

The new project in Springfield will bring $22 million in construction work to the region and is expected to contribute several hundred thousand dollars in annual property-tax revenue to the city.

In this issue, BusinessWest looks at the challenges these projects presented and the impact they will have on future solar installations.

Powerful Arguments

WMECO’s decision to build a large solar-energy facility was groundbreaking, and the first time a project of this size had been built in New England.

“By 2009, 1,200 solar projects had been built in the state. But the majority of them were residential roof-mounted installations or consumer-based systems. There were only 11 on a larger scale and nothing in the utility class,” Frattini said.

WMECO decided to take on the challenge due to a 2008 state initiative.

“Gov. Deval Patrick set a goal of having 250 megawatts of solar power installed by 2017; it is a formidable objective,” Frattini said, explaining that, at the time, the entire country only had 475 megawatts of solar power. The bulk of that was in California, and Massachusetts was producing less than 10 megawatts of solar power.

“The state had a very ambitious agenda for renewable energy. But to help it achieve the goal, the Legislature passed the Green Communities Act, which put policies and mechanisms in place to help with the transition,” Frattini said.

One new provision allowed electric utilities to own up to 50 megawatts of solar generation. Prior to that, they could purchase solar power, but were not allowed to produce it. And in the past, incentives had always been targeted toward small, residential, roof-mounted systems.

The Green Communities Act provided new incentives, tax credits, and zoning provisions for all types of solar-power development.

“Solar is a very expensive renewable technology which is not cost-competitive, so it has to be subsidized,” Frattini explained. “But there was nothing in the utility class, and we figured we could add value by going in where no one had gone before.”

He explained that, since the cost of research and development is built into electric rates, it is utilities’ responsibility to do what they can to reduce their customers’ bills. “So if we can figure out how to lower the cost of solar projects, we will need less in subsidies, which will reduce the burden on our customers,” he said.

In August 2009, WMECO became the first utility in New England to receive approval from the Department of Public Utilities to build solar-energy facilities in the region.

Initially, it began looking at doing rooftop installations on a variety of sites. But as company officials continued to explore options, using remediated brownfield property made more sense.

“The state has more than 490 landfills with 5,000 acres of site potential whose uses are very limited,” Frattini said. And since building a solar-energy facility requires a lot of open space, the company realized it could build large projects that were less expensive on remediated landfills.

The Pittsfield property, which is now owned by WMECO and the Pittsfield Economic Development Authority, seemed like the perfect fit for their needs. The eight-acre site was once owned by General Electric.

The project became a collaborative effort as the Berkshire Economic Development Corp. worked with the city of Pittsfield, WMECO, and the Pittsfield Economic Development Authority to secure the project for Pittsfield.

After obtaining permits and financing to move forward, WMECO put out requests for proposals to the solar industy. “We wanted to use indigenous resources. A lot of the solar equipment wasn’t made in Massachusetts, but we had the technical services already here,” Frattini said, referring to construction equipment, electricians, civil engineering, and legal services.

The utility also wanted to inspire solar firms to develop a new infrastructure. Its work has paid off, and the $9.4 million Silver Lake facility, which was completed last November, proved that large-scale solar projects were less expensive to develop than small projects.

The cost to produce 1.8 kilowatts in the new solar-energy facility was $5,200, said Frattini, adding, “if you build solar into a house, the cost is $6,000 to $8,000 per kilowatt.”

And solar development is continuing.

“In the past year there was more development in Massachusetts than in the total three years before as a result of the new energy policy,” Frattini said. He added that National Grid has two solar projects underway in the eastern part of the state that will produce a total of 5 megawatts of electric power.

“Since we built Pittsfield, we have seen an influx of projects such as these and the one in Amherst,” he said (see related story, page 23).

After completing the Pittsfield project, the question remained as to whether an even larger facility would be even more cost-effective. So, WMECO decided to build again in Springfield. “We are trying to verify if economies of scale are achievable and make the projects worth doing,” Frattini said.

WMECO began looking at the capped Springfield 60-acre landfill in June. And by fall, it decided to move forward. Company leaders were pleased to discover that the solar industry had made advances after the Pittsfield project.

“We were very pleased with the progress we saw in the requests for proposals that were submitted, not just in terms of cost but in their level of preparedness,” said Frattini. “We were trying to help develop the market, and they all came in with viable, actionable proposals. The day we signed the contract, they were ready to go.”

Watt’s Happening?

WMECO is currently in the final stages of formalizing the project, and expects to begin work in April and have the solar facility finished by November. Frattini said it will provide jobs for about 120 union workers.

“It is exciting, and we are verifying our original theory that larger projects can be done in a cost-efficient way. Once it is built, there will be very little maintenance over its 25-year lifetime because there are no moving parts and no fuel costs.

“The excitement is to go where no one else has gone, and do it in a way that resolves a lot of environmental, technical, and business challenges with a variety of stakeholders,” he continued. “In the end, this benefits the community, the people who work in it, the state as a whole, and our customers.”