Foreign Policy

Area Colleges Step Up Efforts to Recruit International Students

Michelle Kowalsky’s business card declares that, among other things, she is the director of International Admissions at Western New England University.

Michelle Kowalsky’s business card declares that, among other things, she is the director of International Admissions at Western New England University.

She’s the first person in the 95-year history of the school to take the title, and that fact speaks to a rather large movement within higher education — and education in general.

Indeed, while schools in this region and across the country have always admitted international students, they have not pursued them in anything approaching the aggressive manner that they are now — for several reasons.

For starters, many schools, WNEU among them, have made it part of their strategic-planning initiatives to become more culturally diverse, because of the many benefits that such a quality brings (more on all that later). Also, there are simply fewer domestic students to pursue as high-school graduation rates continue to decline and schools scramble to fill seats while keeping academic standards high.

And there is an important practical consideration as well. In many cases, the parents — or the government — of the student being recruited is ready, willing, and able to pay full price for the privilege of being educated in the U.S.

Add it all up, and people like Kowalsky are racking up frequent-flyer miles and mastering important phrases in several languages as they engage in what those we spoke with described as a spirited, heightened, but mostly friendly competition for students from China, Saudi Arabia, Central and South America, Japan, and other spots on the globe.

Michelle Kowalsky recently added the title ‘director of International Admissions’ to her business card, and she is one of many to do so in recent years as the competition for foreign students has heated up.

And often, they’re traveling in groups to various countries or working together through initiatives like Study Massachusetts, a consortium of Bay State colleges that promotes and guides international students to study within the Commonwealth, which Kowalsky currently serves as chair.

A quick look at some numbers shows that various schools’ efforts to recruit internationally are bearing fruit — and changing the dynamic on their campuses in the process.

Bay Path University, which had eight international students in 2012, now has 30 (some undergraduate, but mostly graduate), said Jill Bodnar, who also recently acquired the title of director of International Admissions and now works for the school full-time.

Meanwhile, at Springfield College, which has always had a steady, if small, population of international students because of the school’s historic relationship with the YMCA, has seen its numbers rise to include more than 20 nationalities, said Deborah Alm, director of the school’s Daggett International Center.

At UMass Amherst, administrators realized several years ago that, with international enrollment at roughly 1% of the student population, the school lagged well behind other state universities, which were usually at 5% or higher, said James Roache, assistant provost for Enrollment Management. The university set a goal of 3% by 2014 and surpassed that mark, he noted, and expects to hit 5% (roughly 230 students) this year.

Dawazhanme, who came to Bay Path University from Tibet, says she found the school through a Google search, and liked the small size of the campus and the classes.

Anastasia Ilyukhina is among them.

She was a student at Moscow State University and doing some interpreting for Kowalsky and others at a recent conference in that city when she mentioned to the WNEU administrator that she was interested in studying in the U.S.

Fast-forward a few months, and she was on the school’s campus in Sixteen Acres, majoring in International Studies, and enjoying, among other things, the vast variety of foods in this country and a level of interactivity in the classroom between student and teacher that is, well, foreign to her.

“Teachers here are like your friends — you can talk with them after classes or sit with them in the cafeteria and talk about life,” said Ilyukhina, who has designs on one day working in an embassy as a diplomat or interpreter. “It’s not like that in Russia, and that’s one of the reasons I like going to school here.”

For this issue and its focus on education, BusinessWest looks at how and why more people like Ilyukhina are able to enjoy such experiences, and why, for the schools that are hosting them, international recruitment is becoming an ever-more-important part of doing business.

A World of Difference

She is from Tibet, specifically the village of Dzongsar. Her parents are, among other things, yak herders — although there are fewer yak to herd these days, and that’s another story. She found Bay Path University as a result of a Google search for business schools in the U.S. She makes documentary films (she’s done one on yak, for example) and when she returns to Tibet she wants to help her parents and others create new business opportunities.

All of this helps explain why people like Dawazhanme (in her culture, one name is generally used) are now populating campuses like Bay Path’s, and also why schools want to recruit people like her.

“She has a fascinating story … she’s very talented, and she brings so much to the Bay Path community,” said Melissa Morris-Olson, the university’s provost and also a professor of Higher Education Leadership. “Having students like her on campus has certainly helped expand the horizons of our other students.”

The desire to bring people like Dawazhanme to the Longmeadow campus is part of a broader strategy to “expose students to the broader world,” said Morris-Olson, noting that there are several components to this assignment.

“Roughly 60% of our undergraduate students come from first-generation families,” she explained. “Many of those students, if not most, have never been on an airplane; they’ve never been out of the region. We do have study-abroad experiences, but a lot of students don’t have the money to do that, so bringing students here from other places becomes particularly important as one way of internationalizing the curriculum and the campus and exposing our students to students of other cultures.”

Those same sentiments are being expressed by college administrators across the state and across the country, and they certainly help explain what would have to be called an explosion in international recruitment efforts among area colleges.

“Most schools are recognizing that, as the world gets smaller, we need to expose our students to other cultures, and therefore we welcome international students into our classrooms and living places with our students, which enriches all of us,” said Alm, echoing Morriss-Olson and others we spoke with.

But there are many reasons for this phenomenon.

Chief among them is a strong desire among foreign governments and individual families in those countries to send young people to the U.S. to be educated. The reasons why vary and include the comparatively high quality of the education to be found here, as well as a shortage of quantity in the countries in question.

In many cases, these efforts have become organized and sophisticated, and they involve students of all ages, even grammar school.

In China, for example, there are now myriad education agencies, large and small, that exist primarily to link families and students with educational opportunities in the U.S. and elsewhere, said Bodnar, who spent 15 years in China on various business endeavors, including work with a developer to open health clubs for women, and developed a number of contacts on the ground there.

“China was really exploding in every industry, and as that was happening, Chinese families became increasingly interested in their children coming to the U.S. to be educated,” she said, adding that this sentiment exists even though those who do attend a university in China do so free of charge.

Meanwhile, in Saudi Arabia, the government there has stepped up its efforts to send young people stateside to be trained in a number of fields, from healthcare to engineering, said Bodnar, adding that Bay Path wasn’t necessarily targeting young people in that country, but an opportunity presented itself through an education agency similar to those in China.

“We got an e-mail from someone at the agency saying he worked with Saudi students to look for graduate programs in the U.S. and wanted to know if we were interested,” she explained. “We answered in an e-mail, asked for some more details, and it it just took off from there — we were flooded with applications.”

Textbook Examples

To be part of this international-recruitment movement and bring that coveted diversity and other benefits to their campuses, area colleges and universities must be more aggressive in their recruiting, build name recognition for their institutions, forge relationships with those aforementioned agencies and other entities created to facilitate study here — and do all of this within a budget.

Indeed, travel is very expensive, and schools are being creative, and prudent, in when and how they undertake it.

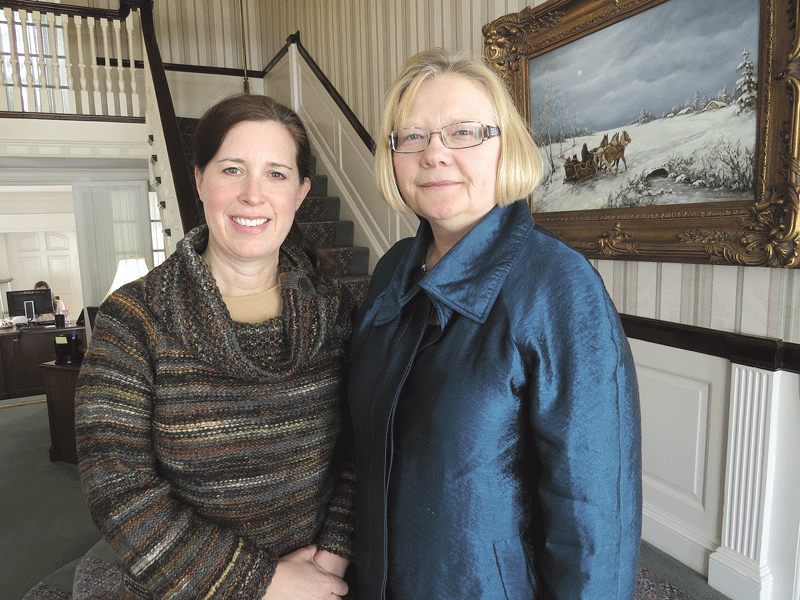

Jill Bodnar, left, and Melissa Morris-Olson noted that Bay Path University has gone from a handful of international students to more than 30 in just a few years.

Overall, said Morriss-Olson, schools must take their commitment to international recruitment to another plane, which Bay Path has done by hiring Bodnar and taking other steps to become a player on the international stage.

“The establishment of Jill’s position really does reflect somewhat of a turning point for us at Bay Path,” Morriss-Olson explained, noting that, while the school has always had a handful of international students on campus — it has long had an exchange program with Ehwa University in South Korea, for example — like other schools, it has dramatically increased those numbers and intends to continue that trend.

At UMass Amherst, the school now recruits from a number of countries, including India, South Korea, and Saudi Arabia, but most of its time and energy is focused on China, said Kregg Strehorn, assistant provost for International Recruitment, who, when asked to describe the school’s overall strategy, summoned the phrase ‘reverse engineering.’

“We’re lucky enough to have been a popular school to attract international students for decades, and what I basically did was gather as much data as a I could about who we were getting applications from, and then really drilling down to find out where we were already popular and why,” he explained. “And then, we’d drill down further into those cities, districts, and those schools to find out why were getting 20 or 30 applications from this one school in Southern China.

“Then, we took it further to find out where we already had students from, and reverse engineered that information,” he went on. “I reached out to those schools and said, ‘we have two students from your school; I’d love to tell you how they’re doing here,’ and by doing that, I was able to develop relationships with individual schools. And that strategy has been very successful — it’s low-maintenance, and it gave us a quick way to jump into the market.”

At WNEU, said Kowalsky, the school’s administration has made a formal commitment to international recruitment, which has manifested itself in a number of ways, including her new title and changed responsibilities (international recruitment was once a minor component of her work; now it occupies roughly 90% of her time) — and a much larger travel budget.

Kowalsky said she’s made several trips in recent years, sometimes by herself but usually as part of a group, to a number of different countries. In recent years, she’s had her passport punched in several Asian countries, but also Brazil, Ecuador, Colombia, and the Dominican Republic.

Her most recent junket was to Guangzhou, China, to attend the China-U.S. Principals Forum for Internationalization of High School Education. The gathering brought together Chinese principals and guidance counselors from 43 high schools across Northwestern China to meet and consult with several U.S. university representatives, with the goal of helping the Chinese educators better guide their students through the U.S. college-application process.

Overall, she said, progress for WNEU in the international forum has come slowly but steadily. It certainly wasn’t something that happened overnight.

“I had said to the higher administration that, if they wanted me to do this, we would need to invest three to five years minimum in order to see any kind of results, because we’re not a brand name; we’re not a household name,” she told BusinessWest. “We needed to really get out there and continuously brand ourselves to reap the benefits down the road. And we’ve definitely seen that, and I’m happy that the administration supported that idea.

“On my first trip, they weren’t looking for me to come back and we’d suddenly have 20 applications or even 10,” she went on. “After that first trip, I don’t think we had even one new student that I could directly tie to that trip. It was more of a continual branding and building of those important relationships.”

Study in Creativity

Patience, commitment, and diligence are all-important qualities in efforts to recruit internationally, said all those we spoke with, because, while this competition is mostly friendly, as mentioned earlier, it is still a competition.

And one that is becoming more intense with each passing year.

Indeed, in the course of her many travels, Kowalsky has seen the number of schools hitting the road escalate and the ranks swell to include Ivy League schools, including Harvard, which enjoy tremendous brand recognition and strong reputations for excellence.

“The landscape has become much more competitive because everybody wants a piece of the international pie, basically, and a lot more schools are traveling,” she explained.

“Until recently, I had never seen Harvard on the road, but this fall I was traveling with a small group of five universities, something we put together ourselves,” she went on. “We were visiting a couple of high schools, and the Ivy League schools were there, which was shocking to me because I had never seen that before. But it’s understandable, because they’re out there competing against each other for the best of the best.”

As they compete against schools across the country, area colleges and universities have some advantages, and some obstacles as well. Clearly, the reputation of the Northeast, and especially Massachusetts, as a place where the world goes to be educated certainly helps, said Morriss-Olson. However, the relative anonymity of schools like Bay Path, WNEU, and Springfield College can be a disadvantage.

Alm noted that, while Springfield College is certainly well-known within the YMCA community and also for programs such as those in the health sciences and rehabilitation, it is not considered an established brand.

“And so we do have to educate the people we talk with about our many other programs and all that we have to offer,” she said, adding quickly that she must often also educate those she meets about the word ‘college.’

In many countries, especially those that were once part of the United Kingdom, ‘college’ translates roughly into ‘high school.’

“In the mindset of parents, ‘college’ is not yet higher education,” she noted. “Explaining what it means in this country is just part of the education process.”

Strehorn said he and others at UMass have had to do their fair share of explaining things as well. Those duties encompass everything from defining phrases like ‘flagship campus’ and ‘university system’ — “there is no translation in Chinese for the word ‘flagship,’” he noted — to making students, parents, and school administrators understand why the top-ranked public school in the region is not located in Boston.

And geography can also be a factor within this competition, Alm went on, noting that, for some in Asian countries, the East Coast is not only much further away than the West Coast, and therefore more difficult and more expensive to travel to, it is also more of an unknown quantity.

While in some respects it is difficult for schools in more rural settings like Bay Path to compete with major urban settings such as Boston, New York, and San Francisco, Bodnar said, many of the students they’re recruiting don’t come from big cities and would rather not go to college in one.

Dawazhanme told BusinessWest that she also looked at Dartmouth, the University of Oregon, and University of Texas in Austin, among others. She was ultimately attracted to Bay Path by the small size of the school and its classes. There were also corresponses with Bodnar that added an attractive personal touch to the process.

“She would write to me almost every month,” she explained. “That gave me a chance to really get to know about the university and the people here.”

Overall, schools will take full advantage of any edge they can get, said Kowalsky, adding that WNEU has an usual one.

“These kids all know The Simpsons, and so they all know about Springfield, and I’m fine with that,” said Kowalsky, noting that, while the show doesn’t identify its host city as being in the Bay State, it doesn’t really matter. “As far as they’re concerned, Springfield is one place in the United States, and if our banner says Springfield and they make an association because of that, I’m fine with it.”

Meanwhile, at UMass Amherst, the school’s name resonates thanks to solid U.S. News & World Report rankings, which are a big factor overseas (the university was recently ranked among the top 30 public schools in the country), as does its celebrated food-services department, ranked first or second in most national polls, said Strehorn.

“My family and I eat in the dining commons once a week — my kids love it, they think it’s a five-star restaurant, and for all intents and purposes, it is,” he told BusinessWest. “Ken Toog (executive director of Auxiliary Enterprises) for the university) has brought an international flavor to it — we serve international food. Last year, I had a bunch of colleagues from China come to visit, and one I’d never met before told me this was the best Chinese food she’d ever had outside of China.”

Course of Action

Kowalsky said that her travels have taken her to a number of intriguing spots on the globe, from Beijing to Rio de Janeiro to Hong Kong, but she hasn’t had many opportunities to take in the sights.

“There’s never really time — when I’m visiting a city, I’m not there long — and besides, I’m not there on vacation,” she said, adding that there is important work to be done, and time and resources must be allocated prudently.

This is a new and different time for colleges across the country, a time to make the planet smaller and bring it to their campuses and classrooms. The race for international students is indeed a competition, but it also represents a world of opportunity — in more ways than one.

George O’Brien can be reached at [email protected]