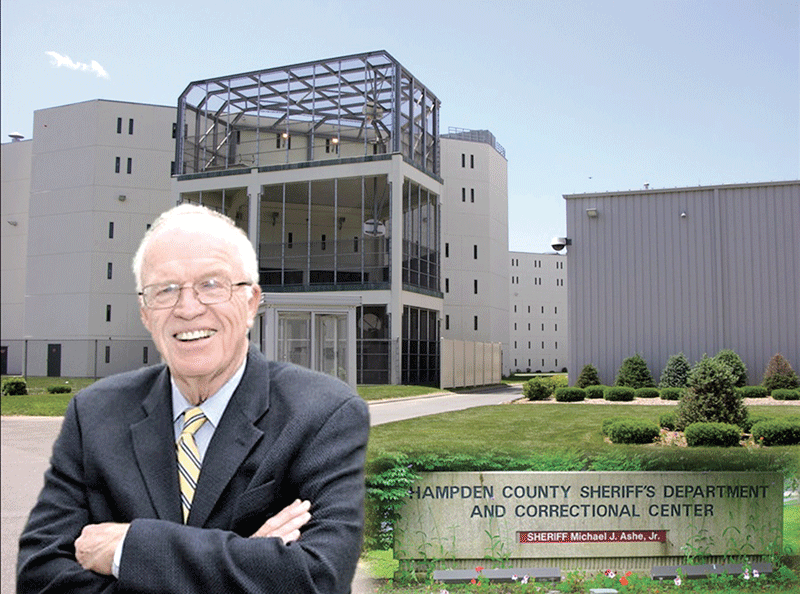

Hampden County Sheriff Michael J. Ashe Jr.

His Career Has Been All About ‘Embracing the Challenge’

Hampden County Sheriff Michael J. Ashe Jr.

Leah Martin Photography

Since taking office back in January 1975, Michael Ashe has spent roughly 15,000 days as sheriff of Hampden County.

The one everyone remembers was that Friday in October 1990 when he led what amounted to an armed takeover of the National Guard Armory on Roosevelt Avenue in Springfield. It was mounted in response to what Ashe considered dangerous overcrowding at the county jail on York Street, built in 1886 to house a fraction of the inmates he was hosting at the time.

The incident (more on it later) garnered headlines locally, regionally, and even nationally, and in many ways it finally propelled Hampden County’s commissioners to move toward replacing York Street — although nothing about the process of siting and then building the new jail in Ludlow would be considered easy.

While proud of what transpired on that afternoon more than 25 years ago, Ashe, now months away from retirement, hinted strongly that he would much rather be remembered for what transpired on the 14,999 or so other days. These would be things that didn’t land him on the 5 o’clock news, necessarily (although sometimes they did) — but did succeed in changing lives, and in all kinds of ways.

Summing up that work, he used the phrases “embracing the challenge” and “professional excellence” for the first of perhaps 20 times, and in reference to himself, his staff, and, yes, his inmates as well.

Elaborating, he said professional excellence is the manner in which his department embraces the challenge — actually, a whole host of challenges he bundled into one big one — of making the dramatic leap from essentially warehousing inmates, which was the practice in Hampden County and most everywhere else in 1974, to working toward rehabilitating them and making them productive contributors to society.

This philosophy has manifested itself in everything from programs to earn inmates a GED to the multi-faceted After Incarceration Support Systems Program (AISSP), to bold initiatives like Roca, designed to give those seemingly out of options one more chance to turn things around.

Slicing through all those programs, Ashe said the common denominator is making the inmate accountable for making his or her own course correction and, more importantly, staying on that heading. And the proof that he has succeeded in that mission comes in a variety of forms, especially the recently released statistics on incarceration rates in Hampden County.

They show that, between September 2007, when there were 2,245 offenders in the sheriff’s custody — the high-water mark, if you will — and Dec. 31, 2015, the number had dropped to 1,432, a 36% reduction.

Some of this decline can be attributed to lower crime rates in Springfield, Holyoke, and other communities due to improved policing, but another huge factor is a reduction in the number of what the sheriff’s office calls “recycled offenders” through a host of anti-recidivism initiatives.

Like the Olde Armory Grille. This is a luncheon restaurant and catering venture (a break-even business) operated by the Sheriff’s Department at the Springfield Technology Park across from Springfield Technical Community College, and in one of the former Springfield Armory buildings, hence the name. It is managed by Cpl. Maryann Alben, but staffed by inmates engaged in everything from preparing meals to cashing out customers.

‘Bill’ (rules prohibit use of his last name) is one of the inmates currently on assignment.

He’s been working on the fryolator and doing prep work, often for the hot entrée specials, and hopes to one day soon be doing such work in what most would call the real world, drawing on experiences at the grille and also while working for his uncle, who once owned a few restaurants.

He said the program has helped him with fundamentals, a term he used to refer to the kitchen, but also life in general.

“I went from being behind the wall to being out in the community,” he said. “And now I’m into the community.”

Bill’s journey — and Ashe’s life’s work — are pretty much defined by something called the “Hampden County Model: Guiding Principles for Best Correctional Practice.”

There are 20 of them (see bottom), ranging from No. 4: “Those in custody should begin their participation in positive and productive activities as soon as possible in their incarceration” to No. 15: “A spirit of innovation should permeate the operation. This innovation should be data-informed, evidence-based, and include process and outcome measures.”

But it is while explaining No. 2 — “Correctional facilities should seek to positively impact those in custody, and not be mere holding agents or human warehouses” — that Ashe and his office get to the heart of the matter and the force that has driven his many initiatives.

“It is a simple law of life that nothing changes if nothing changes,” it reads.

By generating all kinds of change, especially in the minds and hearts of those entrusted to his care, Ashe is the epitome of a Difference Maker.

Coming to Terms

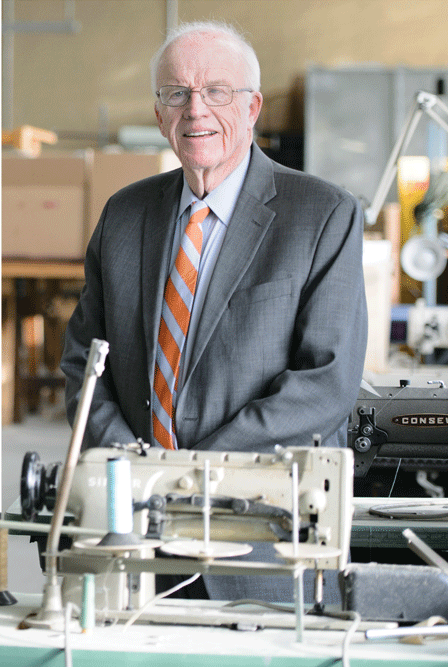

The old and the new: above, Mike Ashe at the old York Street Jail, which was finally replaced in the ’90s with a new facility in Ludlow, bottom.

Ashe told BusinessWest that, when he first took the helm as sheriff in 1975, not long after a riot at York Street, he was in the jail almost every day, a sharp departure from his current schedule.

Perhaps the image he remembers most from those early days was the white knuckles of the inmates. They were hard to miss, he recalled, as the prisoners grasped the bars of their cells, an indication, he believed, of immense frustration with their plight.

“There was a great deal of tension, and you see it in those knuckles.” he said. “Inmates had a lot of time on their hands; people were just languishing in their cells. I think the only program they had at the time was a part-time education program conducted with the Springfield School Department, an adult basic-education initiative. That was it, and it was only part-time.”

Doing something about those white knuckles has been, in many ways, his personally written job description. As he talked about everything involved with it, he spent most of his time and energy discussing how one approaches that work, using more words that he would also wear out: ‘intensity’ and ‘focus.’

Together, those nouns — as well as the operating philosophy “firm but fair, and having strength reinforced with decency” — have shaped a remarkable career, one that he freely admits lasted far longer than he thought it would when he took out papers to run for sheriff early in 1974. It’s been a tenure defined partly by longevity — since he was first elected, there have been seven U.S. presidents (he had his photo taken with one — Jimmy Carter); eight Massachusetts governors (nine if you count Mike Dukakis twice, because he had non-consecutive stints in office); and eight mayors of Springfield — but in the end, that is merely a sidebar.

So too, at least figuratively speaking, are the takeover of the Armory and the building of a new Hampden County jail, although the former was huge news, and the latter was a long-running story, as in at least 20 years, by most accounts.

Recalling the Armory seizure, Ashe said it was a back-door attempt — literally, the sheriff’s department officials gathered at the front door while the inmates were brought in through the back — to bring attention to the overcrowding issue, because all other attempts to do so had failed to yield results.

“We were trying to get people to listen, because it was clear to us that they weren’t listening,” he explained. “We went to the Armory that Friday afternoon and basically evoked a law that went back to the 1700s. Getting into the building was key; once we did that, we knew we’d get everyone’s attention.”

No, the sheriff’s story isn’t defined only by the Armory takeover or his long tenure. It involves how he spent his career working to give his staff less work to do — or at least fewer inmates to guard.

To explain the philosophy that has driven the many ways Ashe has worked to lessen that workload, one must go back to guiding principle No. 2.

“If incarceration is allowed to be a holding pattern, a period of suspended animation, those in custody are more likely to go back to doing what they have always done when they are released,” it reads, “because they will be what they have always been. The only difference may be that they have more anger and more shrewdness as they pursue their criminal career.”

Elaborating on what this principle and the others mean in the larger scheme of things, Ashe said most inmates assigned to his care have been given sentences of seven to eight months. Relatively speaking, that’s a short window, but it’s an important time. And what the sheriff’s office does with it — or, more importantly, what that office enables the inmate to do with it — will likely determine if the individual in question becomes one of those recycled offenders.

So we return once more to the second principle for insight into how Ashe believes that time should be spent.

“Most inmates come to jail or prison with a long history of social maladjustment, carrying a great deal of baggage in the form of histories of substance abuse; deficits in their educational, vocational, and ethical development; and disconnectedness to the mores and values of the larger community,” it reads. “Given the time and resources dedicated to corrections, it is absolute folly in social policy not to seek to address these deficit areas that inmates have brought to their incarceration.”

And address them he has, through programs that have won recognition nationally, but, more importantly, have succeeded in bringing down the inmate count by reducing the number of repeat offenders.

Sentence Structure

As he talked about these programs, Ashe began by offering a profile of his inmates, one of the few things that hasn’t changed much in 40 years.

“Roughly 90% come there with drug or alcohol problems,” he explained. “You’re looking at a seventh-grade education, on average; 93% of them lack any kind of marketable skill; and 70% of the people are unemployed at the point of arrest.

“Everyone knows that, in the state of Massachusetts, no one just happens to end up in jail — they land there after a long period of what I call irresponsible behavior,” he went on, adding that, likewise, no one just happens to correct that behavior and rehabilitate themselves.

Instead, that comes about by addressing those gaps he mentioned, or doing something about addiction, the lack of an education, the shortage of marketable skills, and the absence of a job.

In a nutshell, this is what the sum of the programs Ashe and his staff have created — both inside and outside the prison walls — is all about.

“What I’m most proud of, I think, is that we never waved at those gaps,” he told BusinessWest. “We put together strategies to deal with these issues.”

And as he likes to say — in those principles, or to anyone who will listen — re-entry to society begins on the first day of incarceration.

That’s when an extensive, seven- to 10-day orientation program and testing period begins, one designed, as Ashe said, to let staff “get to know the inmate — let’s find out who this guy is.”

Such steps are important, he went on, because even amid all those common denominators concerning education, addiction, and lack of job skills, there is still plenty of room for individualization when it comes to correctional programs.

Orientation is then followed by a mandatory transitional program, during which the sheriff says he’s trying he capture the inmate’s heart and mind. Far more times than not, he does, although sometimes it’s a struggle.

And as he said, the work has to begin immediately.

“I didn’t want them to languish,” he explained. “In years past, we would have programs, but they would have a beginning and an end, so you had waiting lists; to get into the GED program would take three weeks, to get into anger management would take four weeks, and I didn’t want that.

“If they come in and just languish in a cell for four, five, or six weeks, I’ve lost them,” he went on. “The subculture wins out — the inmates take over.”

There are always those reluctant to enter the mandatory transition program, the sheriff noted, adding that these individuals are sent to what’s known as the ‘accountability pod,’ a sterile environment where there are fewer rights and privileges. In far more cases than not, time spent there produces the desired results.

“Inevitably, what happens is, at the end of two to four weeks, they say, ‘Sheriff, I get it,’” Ashe told BusinessWest. “They say, ‘this is a coerced program … mainstream me; I’ll go to your programs.’ Not all the time, but a lot of the time, inmates will look back and say, ‘Sheriff, I’m glad you forced me to go through this.’”

Elaborating, he said ‘this’ is the process of addressing the various forms of baggage identified in principle 2 — addiction, lack of education, and a lack of job skills. Initiatives to address them include intense, 28-day addiction-treatment programs; GED classes; an extensive vocational program featuring graphics, welding, carpentry, food service, and other trades; and more.

Many of those who take part in the culinary-arts program will then move on to work at the Olde Armory Grille, an example — one of many — of how the work that begins inside the walls can lead to a productive life when one moves outside those walls.

Indeed, roughly 80% of the women who work in various capacities at the grille — and statistics show women enter the county jail with even fewer marketable skills than men — are finding work in the hospitality sector upon release, said Ashe.

To find out how that specific program works, and how it exemplifies all the programs operated by the Sheriff’s Department, we talked to Alben and Bill.

Food for Thought

The grille, which opened its doors in 2009, is in many ways an embodiment of that line explaining principle 2 regarding change. Indeed, there was a good deal of apprehension about this initiative at first, the sheriff recalled, adding that those attitudes had to change before the facility could become reality.

Over the years, it has become one of the most visible examples of the Sheriff’s Department’s focus on providing inmates with a fresh start — and a popular lunch spot for the hundreds of employees at the tech park and the community college across Federal Street.

Sheriff Ashe with Maryann Alben, catering and dining room manager at the Olde Armory Grille.

The restaurant is designed to provide real work experience and training for participants returning from incarceration as they re-enter communities, said Alben, adding that it involves inmates from the Ludlow jail, the Western Mass. Regional Women’s Correctional Center in Chicopee, and the Western Mass. Correctional Alcohol Center. These are inmates in what is known as ‘pre-release,’ meaning they can leave the correctional facility and go out into the community and work.

When asked what the program provides for its participants, who have to survive a lengthy interview process to join the staff, Alben didn’t start by listing cooking, serving, making change, or pricing produce — although they are all part if the equation. Instead, she began with prerequisites for all of the above.

“Self-esteem is huge,” she said. “When most women come in here, they have slouched shoulders … many of them have never had a job before,” she explained, adding that this is reality even for individuals in their 40s or 50s. “You bring them in here, and you try to build them up. Some of them will catch on sooner than others; some of them worked in restaurants way back when.

“We help them understand how to work with customers and leave the jail behind them,” she went on, adding that inmates don’t often exercise their people skills inside the walls, but must hone those abilities if they’re going to make it in the real world.

And many do, she went on, adding that there are many employers within the broad restaurant community who are able and, more importantly, willing to take on such individuals.

In fact, roughly 87% of those who take part are eventually placed, usually in kitchen prep work, she said, a statistic that reflects both the need for good help and the quality of the program.

Bill hopes to be a part of the majority that uses the grille as an important stepping stone.

“This is the next step in getting back into the community 100%,” he explained. “Not only with getting up early with a job to go to five days a week, but in the way it prepares me mentally and fundamentally for the next step into the real world.”

Such comments explain why an inmate’s final days at the grille involve more emotions than one might expect.

Indeed, the end of one’s service means the beginning of a new and intriguing chapter, which translates into happiness tinged with a dose of apprehension. Meanwhile, there is some sadness that results from the end of friendships forged with customers who frequent the establishment. And there is also gratitude, usually in large quantities.

“We’re giving them a chance to prove themselves,” said Alben. “And when they leave here, most of all them will say, ‘thank you for believing in me.’”

If they could, they would say the same thing to Sheriff Ashe. He not only believed in them, he challenged them and held them accountable, a real departure from four decades ago and what could truly be called white-knuckle times.

No Holds Barred

When asked what he would miss most about being sheriff of Hampden County, Ashe paused for a moment to think back and reflect.

“I think I would have to say that it’s the challenges, embracing the challenges,” he said one last time. “I’ll miss the work of recognizing the problems that our society faces and trying to come up with solutions.”

That answer, maybe as much as anything that he’s done over the past 41 years and will do over the next 11 months, helps explain why Ashe will be remembered for much more than what happened at that National Guard Armory.

And why he’s truly a Difference Maker.

George O’Brien can be reached at [email protected]

Guiding Principles of Best Correctional Policy

(As developed by the Hampden County Model, 1975-2013)

1. Within any correctional facility or operation, there must be an atmosphere and an ethos of respect for the full humanity and potential of any human being within that institution and an effort to maximize that potential. This is the first and overriding principle from which all other principles emanate, and without which no real corrections is possible.

2. Correctional facilities should seek to positively impact those in custody, and not be mere holding agents or human warehouses.

3. Those in custody should put in busy, full, and productive days, and should be challenged to pick up the tools and directions to build a law-abiding life.

4. Those in custody should begin their participation in positive and productive activities as soon as possible in their incarceration.

5. All efforts should be made to break down the traditional barriers between correctional security and correctional human services.

6. Productive and positive activities for those in custody should be understood to be investments in the future of the community.

7. Correctional institutions should be communities of lawfulness. There should be zero tolerance, overt or tacit, for any violence within the institution. Those in custody who assault others in custody should be prosecuted as if such actions took place in free society. Staff should be diligently trained and monitored in use of force that is necessary and non-excessive to maintain safety, security, order, and lawfulness.

8. The operational philosophy of positively impacting those in custody and respecting their full humanity must predominate at all levels of security.

9. Offenders should be directed toward understanding their full impact on victims and their community and should make restorative and reparative acts toward their victims and the community at large.

10. Offenders should be classified to the least level of security that is consistent with public safety and is merited by their own behavior.

11. There should be a continuum of gradual, supervised, and supported community re-entry for offenders.

12. Community partnerships should be cultivated and developed for offender re-entry success. These partnerships should include the criminal-justice and law-enforcement communities as part of a public-safety team.

13. Staff should be held accountable to be positive and productive.

14. All staff should be inspired, encouraged, and supervised to strive for excellence in their work.

15. A spirit of innovation should permeate the operation. This innovation should be data-informed, evidenced-based, and include process and outcome measures.

16. In-service training should be ongoing and mandatory for all employees.

17. There should be a medical program that links with public health agencies and public health doctors from the home neighborhoods and communities of those in custody and which takes a pro-active approach to finding and treating illness and disease in the custodial population.

18. Modern technological advances should be integrated into a correctional operation for optimal efficiency and effectiveness.

19. Any correctional facility, no matter what its locale, should seek to be involved in, and to involve, the local community, to welcome within its fences the positive elements of the community, and to be a positive participant and neighbor in community life. This reaching out should be both toward the community that hosts the facility and the communities from which those in custody come.

20. Balance is the key. A correctional operation should reach for the stars but be rooted in the firm ground of common sense.