Industrial Canvas

Indian Orchard Mills Creates a Community for Artists

Sarah Concannon is a very recent addition to the tenant population at Indian Orchard Mills, but she is already enamored with the sense of community she says exists there.

She calls it “The People in Your Neighborhood,” and it involves painting a portrait of a resident (of her choosing) from each of Springfield’s 17 recognized neighborhoods.

At this point, she’s still in what would be considered the planning and fund-raising stages of this endeavor. While contemplating a process for selecting her subjects, she’s also going about the task of amassing the nearly $7,000 she estimates she’ll need to complete the project; she recently ventured onto Kickstarter, a website that provides a vehicle for crowd-funding creative initiatives via the Internet.

“This is probably the only way I’d be able to fund a project like this,” she told BusinessWest, adding that she recently took one big step forward with this initiative — and what amounts to a fledgling business venture. That would be her move, just a few weeks ago, into a 100-square-foot studio at the Indian Orchard Mills in Springfield.

This step up, from a studio (of sorts) in a small spare bedroom in her home in Springfield, provides her with the physical space with which to flex her creative muscles while she continues her day job as an inventory-control analyst for Baystate Health. But it also gives her much more.

Indeed, she’s now part of what can only be called a community of artists at the sprawling mill complex, one that is fueling the economy in many respects, and also providing a strong support network for artisans trying to make dreams come true and, in many instances, turn passions into successful businesses.

There are now more than 50 artists in the 300,000-square-foot, 12-building mill complex, said Charles Brush, who used that term to describe individuals creating everything from jewelry to furniture to exhibits for the Basketball Hall of Fame.

Brush bought the landmark in 1998 and has committed himself to continuing — and expanding — the work started by the mill’s previous owner, Muriel Dane.

Her name is on the 2,000-square-foot gallery in the mill, which is one focal point of twice-yearly open studio events, said Brush, noting that what Dane created, and he took to a higher level, is much more than physical space in which to paint or sculpt.

“You’ll never see an environment like this anywhere else,” he noted, “because I work with the tenants, and we all work with, and for, each other, with one goal in mind, and that is just to get it done and make it right, whatever ‘it’ happens to be.

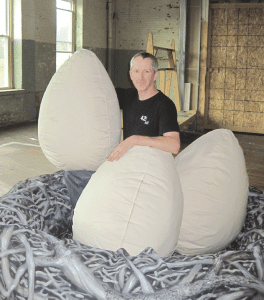

Todd Harris’ company merges engineering and art to create unique museum exhibits like this larger-than-life eagle’s nest bound for a Connecticut learning center.

The story being written in each of the studios is different in some respects, although there are common denominators — a passion for art and a desire to be part of this community of artisans.

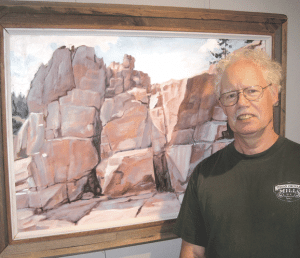

For some, like Peter Barnett, a fine landscape and portrait artist and retired systems analyst at MassMutual, his work is still mostly a hobby, albeit a full-time pursuit.

“I paint things that turn me on, clouds and rocks,” he joked, adding, “I don’t personally need to sell work to keep food on the table, but I do love to sell work, and I really like the community, the interaction, I find here.”

For others, like Todd Harris, the mill has become home to a new business venture. He left a lucrative career as an engineering consultant to start 42 design fab, which creates exhibits for museums and nature centers across the country.

“We’re trying to make this work as a business and support the whole creative-economy thing because you should be able to make a living for a team of people that come to work every day and have fun doing creative things,” he said. “Our growth plan is about pushing our boundaries artistically and making it work as a business.”

For this issue and its focus on the region’s burgeoning creative economy, BusinessWest takes an in-depth look at one of the most recognizable — and successful — manifestations of that phenomenon, the Indian Orchard Mills, a landmark that speaks to the region’s past, but is now a symbol of its future.

Brush Strokes

Crystal Popko says people will invariably have two questions when they first encounter her jewelry made from butterfly wings.

“‘Are they real?’ and ‘what happened to the butterfly?’ — that’s what everyone wants to know,” she said, adding that the answer to the first query is ‘yes,’ and the response to the second is that the insect died naturally. (She acquires the wings from a nearby butterfly conservancy.)

Popko, who also works with fused glass as well as feathers, leaves, and other products from nature, is typical of the dozens of artists who now call the mill complex home.

Like many artists aspiring to turn their talent into a business, she started working out of her house. She would spend summers working, seven days a week, as a waitress on the Cape, trying to earn enough to spend her winters making and selling jewelry.

Three years ago, she decided to make her art a career, knowing that she would need, among other things, a studio where she could create and clients could see her work. She said she was drawn to the mill by its location, attractive lease rates, and, most importantly, that aforementioned community of artists already doing business there.

Carol Russell, a creator of stained-glass art, moved in for the same reason.

“I came here for the sense of community,” she told BusinessWest, “and being around other people and their energy.”

‘Community’ and ‘energy’ are words one hears often while walking the hallways of the mill complex, said Brush, who has a background in finance and manufacturing, but admits to being initially overwhelmed by the mill, its size, and all that goes into its upkeep.

But he was too intrigued by its vast potential to walk away when he started thinking about acquiring the mill in 1997. And he has no regrets about what most would consider a risky undertaking.

“It looked like it would be fun, and it’s really been a blast,” he said. While a number of industry groups (from asbestos abatement to precision manufacturing) are represented on a tenant list that now numbers more than 130, he noted, the growing number of artists — and the wide diversity of that constituency — is what has given the mill much of its identity.

“Everybody has a different definition of art,” he noted, adding quickly that his is quite broad, largely because of what he sees happening on each of the mill’s five floors. “Some people think artists stand at easels or over a lump of clay — and we have those in droves — but in my mind, arts is the creative, like the guy [Harris] that makes the museum exhibits. Yes, it’s manufacturing, but there is a lot of art that goes into what they do.

“What our woodworkers do with raw materials, what leaves here — the cabinetry, the furniture — is all art,” he went on. “We are a creative-industry complex, and as far as I’m concerned, the industry is just as artistic as traditional art.”

In his role as landlord, Brush says it’s his job to give all of his tenants an environment in which they can thrive. And when it comes to the artists — of all kinds — this means providing the space and the opportunity to create, collaborate, and feed off that aforementioned energy.

Peter Barnett has enjoyed the creative interaction of the artists at Indian Orchard Mills for two decades.

The gallery is open Saturdays from noon to 4 p.m., and it features works created by many of the mill’s tenants. Open year-round, the gallery allows each artist the opportunity to produce their own show for a month; Concannon’s “The People in Your Neighborhood” is expected to be ready for display in the gallery next year.

As for the open studios, they are, as the name suggests, events where tenants open up their studios to the public, with works on display and for sale.

Now in their 21st year, these events have drawn thousands of visitors to the mill (necessitating their expansion from one-day affairs to two) and, in so doing, have inspired a number of artists to join the community at the mill.

Such was the case with Concannon, who took in one of the open studios several years ago and began formulating plans to one day be one of the artists greeting guests. That day became reality a few months ago, when she and her husband, Greg Matthews, determined that they had the financial wherewithal for her to make her painting more than a part-time pursuit.

“It’s so inspiring to be a part of a community where people speak the same language and can offer critiques of your work if you want it,” said Concannon. “I can’t wait to get started because I know how good it will feel to be painting again and what a sense of accomplishment awaits if I’m able to make this project successful.”

His Nest Eggs

As he talked with BusinessWest, Harris showed off a larger-than-life eagle’s nest, complete with three oversized eggs, that is in the final stages and bound for the Harry C. Barnes Memorial Nature Center in Bristol, Conn.

It’s an example of how his company has merged engineering and art to create unique learning experiences, and also one of the hundreds of unique and diverse forms that the creative economy takes in the region — and especially Indian Orchard Mills.

There, tenants haven’t just created works of art. They’ve created a community — and real momentum in the efforts to make this sector an economic driver.

Elizabeth Taras can be reached at [email protected]