Just Passing Through

Robert E. Barrett Fishway Offers Learning Experiences on a Grand Scale

Paul Ducheney says the fishway was the culmination of years of study involving fish behavior, as well as considerable trial and error.

But it was. Well, sort of.

As legend has it in Holyoke, in 1955, an Atlantic salmon was trying to make its way north on the Connecticut River, back to its birthplace to spawn, when it hit what was then a roadblock — the Holyoke Dam. The story goes that an engineer with what was then the Holyoke Water Power Co. caught the confused fish with said net, but then didn’t know what to do with it.

“So they said, ‘well, lets put it in a bucket of water and bring it up over the dam and dump it in,’” explained Ducheney, superintendent for Electric Production at the Holyoke Gas & Electric Department (HG&E), which acquired the dam in 2001. “And that was pretty much the start.”

Today’s Robert E. Barrett Fishway is the result of that ongoing story of how, through the use of exponentially more sophisticated means of fish attraction and larger buckets, HG&E has created a fishlift that has become a model for hydropower systems in this country and around the world.

The two-bucket system carries hundreds of thousands of anadromous fish — those born in fresh water (salmon, smelt, shad, striped bass, and sturgeon are common examples), and spend most of their life in the sea, but return to fresh water to spawn — over the dam each year so they continue their migratory journey north.

And while doing so, it provides powerful lessons to visitors, many of them schoolchildren on field trips, about these fish, hydropower, and how they can coexist.

This was the dream of Robert E. Barrett, former president of the Holyoke Water Power Co., whose imagination and perseverance made it reality.

The current fishway, opened in 1955, hosts more than 11,000 visitors a year between April and June, when the fish make their annual treks north, said Kate Sullivan, marketing coordinator for the HG&E, who told BusinessWest that the facility is still far too much of a best-kept secret from a tourism perspective, and that the utility is working to see that it loses that distinction.

“People are always amazed; they can’t believe this is in their own backyard,” said Sullivan. “And this was part of Robert Barrett’s mission, to make this an educational experience for kids, too.”

For this issue and its focus on travel and tourism, BusinessWest paid a visit to the fishway for an educational experience on a grand scale — in more ways than one.

Current Events

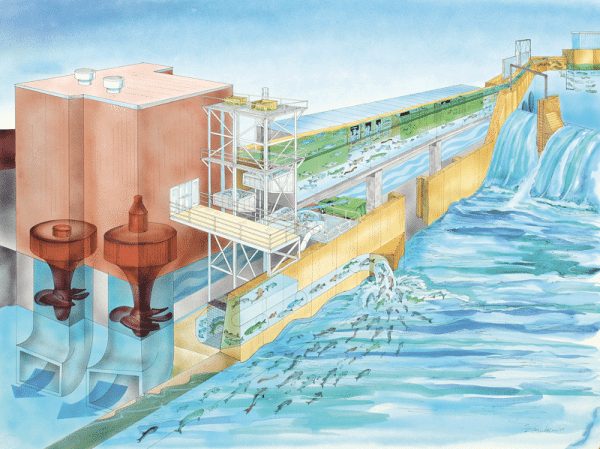

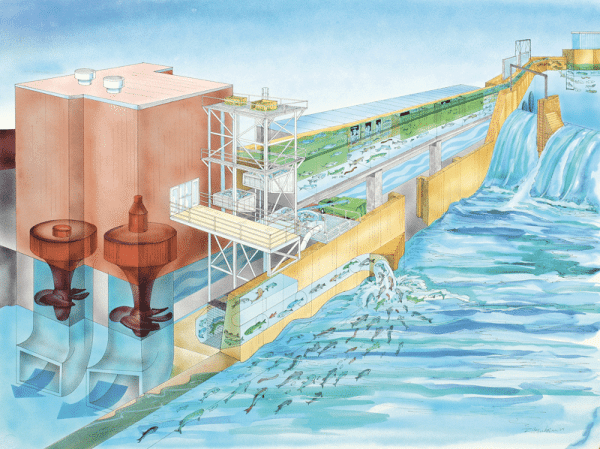

This illustration shows how the fishway enables migratory shad, Atlantic salmon, and other species to be collected, lifted in buckets over the dam, and released.

Illustration by Robert Oxenhorn

But the fishway in Holyoke is somewhat unique because of the breadth and depth of the educational opportunities it provides and the large scale of the operation. Indeed, it is said to be most successful fishlift on the Atlantic coast in terms of the number of fish it ferries.

For visitors, it’s an opportunity to see how nature and modern technology can collaborate and create some powerful images.

Once through the entrance of the power station, visitors are led — on the right, past the giant HG&E turbines that harness the river’s power, and, on the left, past a series of historical pictures of the dam and older fish-assisting devices — out to the large outdoor observation deck. Standing high above the Connecticut River on the deck, they get a southern view of the river and the special canal, which shows the two ways fish enter the gathering area by way of a high-velocity water flow that attracts them to the main collection area just under the deck.

Visitors can then turn their attention to the north and experience the sights and sounds of water coming over a section of the dam, next to the lift structure. On the half-hour, a buzzer rings, signaling the start of the fishlift as its two large buckets begin carrying hundreds of fish and water more than 50 feet up and into an exit flume. This is the point where visitors then move inside to see the fish swim by the public viewing windows, giving them the feeling of being underwater with the fish.

Sullivan told BusinessWest that guided school-group tours take about an hour, which includes time for an activity.

“And this is very unique,” added Ducheney. “If you go to other lifts at other dams, they’re sort of separate from the powerhouse, so it’s pretty neat to see power generation integral with fish passage. It’s Holyoke’s best-kept secret.”

But that secret took some time to materialize.

Kate Sullivan says grassroots efforts have helped increase visitorship at the fishway, which is open only a few months a year.

Since 1794, several dams have been constructed at South Hadley Falls, where the river drops more than 40 feet, and in October 1849, a large ‘timber crib’ dam was constructed, preventing upstream fish migration.

In 1866, Massachusetts enacted legislation requiring the construction of devices to permit passage of shad and salmon, which resulted in the first wooden fish ladder in 1873 — a system designed to replicate nature — on the South Hadley side of the river. However, the ladder was off the beaten path of the fish’s instinctual travels, said Ducheney, and fish passage didn’t go well; in fact, not one fish used any of the early ladders.

In 1900, the current, much larger dam made from Vermont stone was built, and in 1949, HWP received a license from the Federal Power Commission for the Holyoke Hydroelectric Project. As part of the license, HWP was required to “construct, maintain, and operate fish-protection devices.”

Soon after, the aforementioned lucky Atlantic salmon was saved and lifted over the dam. The stiffer federal mandate had engineers building a different type of fish passage because others hadn’t worked. More research into fish behavior resulted in the reason why: fish needed to sense the sound and current of rushing water on their journey, where a dam now stood. The solution was to create a gathering area by way of a high-velocity water flow that attracts the fish to the main collection area just under the deck, and the first lift, using a bucket in 1955, was built under Robert Barrett’s direction — the first successful fishlift in the country.

“It’s very important for the ecosystem,” Ducheney noted. “From a regulatory basis, today we have a mandate from the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission to operate the dam, and part of the conditions is to provide for safe and effective fish passage.”

Today, fish can continue upstream migration (if they’re not collected for hatcheries), where fishways further upstream at the smaller Turners Falls, Vernon, and Bellows Falls hydroelectric projects also provide a means to enhance passage for migrating species through a simpler elevated step process.

Hook, Line, and Sinker

When HG&E purchased the Holyoke Dam to operate the hydroelectric facilities and the Holyoke Canal System, more improvements were made to the fishlift, Ducheney explained to BusinessWest.

“It’s automated now, so it runs without operator intervention, and it’s tripled in size, so we can accommodate many more fish,” said Ducheney. “In fact, this lift has become a model for others, including the Susquehanna River and in Japan, China, Brazil, and European countries. Holyoke is pretty well-known for fish passage.”

And the fishlift is a first for something else that’s important.

“Literally, every fish is counted,” said Sullivan, noting that the Holyoke Dam is the first that fish encounter as they move north from Long Island Sound, so keeping accurate inventory is critical to tracking what happens to fish before and after they get to the Paper City.

The counters are biology students from Holyoke Community College who click a designated counter for each species of fish in a special viewing room just past the public viewing windows; its another form of educational experience of which Barrett would be proud.

Since the official counts started in 1965, the most prolific years for fish passage were in 1985 and 1992, at more than 1 million fish. In 2012, more than 500,000, mainly shad, were lifted over the dam.

Shad, said Ducheney, is a river herring, and while that may not sound delectable, he noted that shad is actually on the menu at New York’s famous Tavern on the Green restaurant at this time of year.

But restaurants aren’t the only interested parties when it comes to shad. The annual HG&E Shad Derby, one of the region’s largest fishing events, is held on two weekends in May and offers nearly 600 anglers of all ages the opportunity to win cash prizes and write plenty of their own fish stories as they enjoy the recreational benefits of the Connecticut River.

Marketing funds are tight, Sullivan said, so getting the word out about the fishway is a struggle. But thanks to HG&E’s newsletter to 18,000 customers, as well as more comprehensive grassroots efforts over the past couple of years to increase awareness of the facility, visitation has increased.

In just a short window of six weeks, from late April to mid-June, more than 11,000 visitors came through the fishlift last year, 2,000 more than in 2011, said Sullivan, noting that many of them are students from across the region.

The fishlift is open Wednesday through Sunday, 9 a.m. to 5 p.m., until June 16, due to the spawning season each spring. Also open on Memorial Day, the facility offers visitors of all ages a unique combination of science through tourism, and a chance to tell a real fish story about the ones that got away — or at least further upstream.

Elizabeth Taras can be reached at [email protected]