Microenterprise Program Helps Refugees Launch Businesses

Land of Opportunity

After years in a Nepalese refugee camp, Gokul Budathoki and Mena Tiwari found a new life — and business — in Springfield.

If all Ascentria Care Alliance did for refugees was help them get established in the U.S. and find jobs, it would be important work. But, thanks to an initiative launched in 2010 called the Microenterprise Development Program, Ascentria is actually putting many of its clients on the road to business ownership, through education, assistance with permitting and other hurdles, and small loans. The result, so far, is a patchwork of intriguing startups across the Pioneer Valley owned by people who truly appreciate their new opportunity, and have their sights set on continued growth.

Mena Tiwari’s story begins much like that of many refugees.

She was born in Bhutan, but, at age 2, her family fled that country’s inter-ethnic conflict, and she wound up in a refugee camp in Nepal, where she spent the next two decades.

While growing up there, owning a business — in the United States, no less — was the furthest thing from her mind.

“Back in the refugee camp, we didn’t get the chance to do anything like that,” Tiwari said, noting that her family ran a little shop in the camp, but it resembled in no way the complexity of opening a store in the U.S.

“Basically, we had a lot of love, but we didn’t have money,” she said, recalling how people would work with their hands — carving sandalwood into sticks for incense, for example — to make a little profit, and if they were able to scrape up enough for, say, a picnic outing, they appreciated it. “I always look for happiness in the little things. They made me happy because I worked for it.”

Tiwari met Gokul Budathoki in the camp, and after they immigrated to the U.S. — she in 2009, staying with family in Buffalo, N.Y., and he to New Hampshire in 2011 — they reconnected, and eventually married in late 2011; a year later, to the day, their son was born.

Tiwari worked in a salon as a hairdresser before moving to New Hampshire after the wedding, and Budathoki had been working at a Walmart, gaining a knowledge of retail he would put to use when the couple started talking about opening a business.

“Nobody was here to support us; her parents were in Buffalo, and my parents were back in country, so we had to support ourselves,” said Budathoki, who eventually enrolled at a community college and landed a new job with a mental-health nonprofit. “We said, ‘why don’t we open our own thing?’ So, after the baby was born, we put him in the carseat and drove around the countryside, looking.”

What they found was a new life in the Pioneer Valley — as proud owners of Interstate Mart near the ‘X’ in Springfield — with the help of the Microenterprise Development Program at Ascentria Care Alliance.

“We’re a resettlement agency,” Emil Farjo said of ACA, which has offices in Westfield and Worcester and was previously known as Lutheran Social Services. “We have refugees come from overseas, and we help them get an apartment, furniture, their first IDs, benefits from welfare and MassHealth, Social Security numbers, and ESL classes.”

Beyond those basic services, however, is the microenterprise program, which was created in partnership with the federal Office of Refugee Resettlement in 2010, with the goal of helping refugees launch businesses and reach economic self-sufficiency.

Nazar al Khaled was a famous singer in Iraq; now he hawks his wife’s authentic cuisine in West Springfield.

Farjo was hired to lead the program in 2012, leveraging his education, background in computer science, and experience as a business owner in Iraq, where he’d owned three very different enterprises, in engineering and HVAC, food distribution, and wholesale.

After fleeing Iraq in 2004 for the safety of his family and spending six years in Syria, he immigrated to the U.S. and connected with what was then Lutheran Social Services, working with other refugees on computer classes, vocational training, and other skills before being tapped to lead the business-startup program.

“I was very successful in my business, but when we fled our country, we left everything behind,” he told BusinessWest. “My experiences help me understand how these people think. I can be a bridge from their former country to the American system. This is my passion. I find everyone’s success is my success. I love what I’m doing, and I want to help them make their dreams come true.”

First Steps

The microenterprise program provides business planning, financing, and training to refugees in the Bay State. Applicants receive guidance in budgeting, marketing, finance, and obtaining permits and licenses. Typically, refugees lack sufficient credit history or loan collateral to receive traditional business loans, so the program provides small startup loans, typically in the range of $500 to $15,000.

To date, the program has helped spawn 32 businesses in Greater Springfield and 12 more in Worcester, ranging from child care to cleaning services; web-based services to landscaping and farming; delivery services to auto repair. Most owners are Iraqi or Bhutanese, with a smattering of refugees from Liberia, Lithuania, and Burundi.

“They’re new to the system, so we provide classes in financial literacy and money management, how to write a business plan, how to budget,” Farjo said. “We’re also a microlender; we don’t ask for credit, we just want them to take their first steps in business loans, and prepare them for the next step, which is traditional loans from traditional lenders.”

Mike Garjian, a serial entrepreneur who has been working with Farjo in the program, added that these classes tend to be full. “There’s a thirst for knowledge; they’re fully engaged. And that translates to business success.”

Farjo also works one on one with participants on hurdles such as site selection, licensing, and permitting. “They would be lost without us. We’re dealing with surrounding cities, and each city is different. It’s a hassle for them.”

For Tiwari and Budathoki, the hassles since opening almost 10 months ago have been worth it. Their store sells both American and ethnic food products, as well as an impressive array of Bhutanese clothing. Their customer base has been steadily growing, and they’re looking to establish a space for community gatherings in additional space at the back of the store.

“It began with a little stress,” Tiwari said, “but we can say we are happy.”

Nazar al Khaled is also pleased with his new business. He was a famous Iraqi singer — “very famous, not normal famous,” he noted — whose life, like that of so many countrymen, was turned upside down after the U.S. invasion in 2003. He caught a bit of a break when the New York Times and other sources reported him dead in an airstrike in 2004, as some Muslim groups that rose up after Saddam’s fall were targeting singers and other artists, and the report took some of the pressure off.

In 2009, he arrived in the U.S. with his family and stayed for a couple of years in New York before moving to Western Mass. in 2011 for a quieter lifestyle.

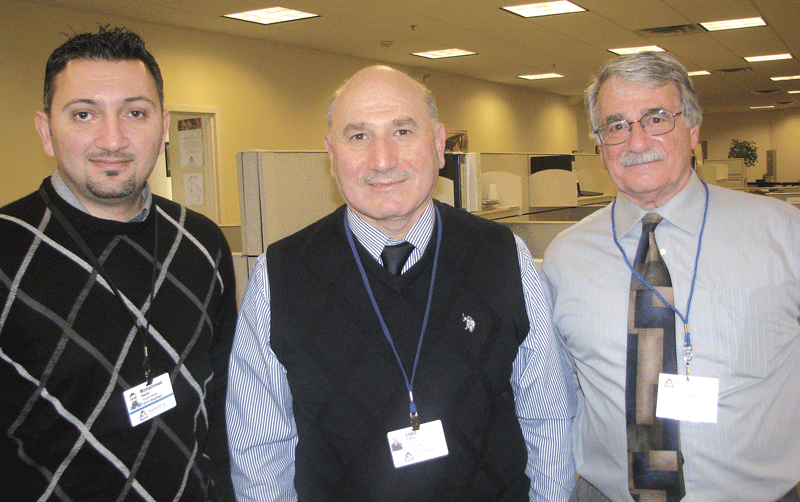

From left, Mohammed Najeeb, program director at Ascentria, with Emil Farjo and Mike Garjian.

Recently — recognizing the culinary skills of his wife, Asmaa Mohammed, and wishing to go into business for himself — al Khaled connected with Farjo and opened Ahalna Foods on Main Street in West Springfield, a multi-ethnic neighborhood where eight of Ascentria’s refugee clients have launched enterprises. To hear him tell it, he definitely needed Farjo’s help.

“In America, there are many ways to start work, but no one tells you the right way,” he said of his earlier dealings with banks and municipal officials. “There are many rules, and nobody answers you, nobody smiles at you, nobody does anything for you. I say, ‘I want to open this business.’ They say, ‘OK, come back next month.’”

Ascentria, on the other hand, “brings us together and teaches us how to work with the banks, how to start a business,” he went on. “Any license or anything else we need, they help us with that.”

Iraqi cuisine, al Khaled said, is based on tradition that extends back 8,000 years, adding that his wife’s creations — which lean heavily on beef, lamb, and chicken — are meant to be savored by all the senses and demand the diner’s entire focus, as opposed to American “technology food” (his term for heavily processed fare) swallowed quickly in front of the TV.

Currently, Ahalna prepares meals for takeout, but also caters events, and aims to eventually move into wholesale distribution. So far, his clientele is mainly people who have already experienced and enjoy Iraqi fare, but he hopes to attract Americans who seek an authentic culinary experience.

“Americans don’t want to change,” he said, “but some Iraqi families have friends and neighbors, and when they bring them our food, they give it a taste and find it’s something different, and after that, they come here to buy it.”

Untapped Potential

Garjian believes Ascentria’s success helping refugees launch businesses should receive more attention than it does.

“This is a sector that’s been really invisible, but it’s a very powerful and interesting component to the region’s economic vitality,” he said. “They are competent, highly energized people.”

He recalled hiring a Vietnamese refugee from Lutheran Services 20 years ago for one of his businesses. She had been a mathematician in her homeland, but had never worked with computers. After he introduced her to one and showed her how to operate Excel, she was quickly running complex equations. What Ascentria’s microenterprise program does, he noted, is help people with these types of skills — or at least the potential to quickly attain them — achieve business success in a very different environment from where they began.

Take the three Iraqi refugees who operate Chicopee Auto Service & Sales Center on Front Street, for example. “We did not want to work for anybody,” said Ahmed Mustafa, who partnered with his brother, Abraheem Mustafa, and a friend, Omar Abdul Razzak, to establish the business early in 2015. They arrived in the U.S. by way of Syria after fleeing their homeland a few years after the invasion.

From left, Abraheem Mustafa, Ahmed Mustafa, and Omar Abdul Razzak are partners at Chicopee Auto Service & Sales Center.

“It was the war,” Ahmed Mustafa said when asked why they left. “It’s always the war.”

But he credited Ascentria and Farjo for helping the partners navigate the permitting process to launch the business, on the site of a former, then-closed used-car dealership. They started with 13 cars for sale and now have 25 on the lot, and typically service about 15 cars at any given time. They recently installed a second repair bay to conduct alignments, and do state safety inspections as well.

Mustafa said there are challenges to starting a business, but he welcomes some of them, like the gradually growing presence of other auto-related businesses in the Chicopee Falls neighborhood. “Having more than one dealer is better for the business that has better prices and better quality,” he said, already speaking the language of a businessman who embraces competition.

Growing the business will bring other benefits as well, he added, not the least of which is being able to hire other immigrants, especially those who struggle with the English language and, therefore, find it challenging to land a job.

Farjo has high hopes for all the businesses his agency helps launch, but he always cautions against overly optimistic expectations.

“They need to be patient. They might not be successful right when they open. Taking a risk is not easy. Starting a business is not easy, even for Americans,” he said. “But when they find someone who will speak with them as a person, someone who cares, that makes a difference. I just want to go the extra mile to see these people be successful, and at the end of the day, they thank me for helping them out.”

Credit Where It’s Due

Budathoki and Tiwari say they have qualities that complement each other: his fortitude and her business mind, for starters. But both say Ascentria was a key element in their success.

“I cannot thank them enough,” Tiwari said. “We wanted to find a way to find success and feed our family, but we went to City Hall and and so many places before we met with Emil. Back in my country, I didn’t know the meaning of a business plan.”

But Farjo says his agency is merely helping them open doors. “They have our support, but it’s their skills and ambition and effort that makes them succeed.”

In a country that accepts some 70,000 refugees a year, Garjian said the microenterprise program serves a social purpose even beyond raising the standard of living for its handful of participants and boosting economic development region-wide. At a time when so many Americans look suspiciously at immigrants and refugees, these small-business owners (who are, like anyone who receives Ascentria’s services, thoroughly vetted and screened) might well be changing a few perceptions.

“Many of them are coming from areas of tyranny and loss of hope,” Garjian told BusinessWest. “To them, each breath is a gift. I’ve seen people walk off the elevators here and take their first breath of freedom. That’s so profound to me.”

Joseph Bednar can be reached at [email protected]