Prospect Meadow Farm Provides Jobs, Therapy

Growth Opportunities

Aerial Mehler with ‘Snowy,’ her pet goat.

When Prospect Meadow Farm was conceived six years ago, the thinking was that working outdoors and with animals could have a significant therapeutic effect on those with autism or developmental disorders. “That’s something I believed in before this started, but I didn’t quite know how powerful it was,” Shawn Robinson noted, adding that he certainly knows now.

Aerial Mehler grew up on the western end of Long Island, just a short train ride from Manhattan. So, in most all respects, she considers herself a city girl.

Thus, when her family relocated to Western Mass. several years ago, her first reaction was that this region was, in all likelihood, too rural for her liking.

And when she was approached about working at Prospect Meadow Farm in Hatfield, a vocational-services program operated by Northampton-based ServiceNet, after becoming frustrated at a few other employment settings, she was more than a little dubious about the notion that she would soon warm to the place, vocationally and otherwise.

“I thought, ‘I’m from the city — I don’t do this stuff,’” she told BusinessWest, adding that today … well, she does do that stuff, or at least some of the many things that fall into the broad realm of agriculture and farm management.

In fact, she is the program assistant to the facility’s director, Shawn Robinson, and carries out a host of administrative duties ranging from sending out bills to the farm’s many customers, especially those who purchase its eggs and log-grown shiitake mushrooms, to drafting reports to the state, to maintaining the farm’s Facebook page.

“I call myself the on-call employee, because if something needs to be done, I do it, and it’s something different every day,” said Mehler, 29, who actually owns one of the goats now living at the farm, a spirited white female appropriately named ‘Snowy.’

“I’d say I’m a regular here, but that’s a setting on a washing machine,” she joked, expressing an opinion held (if not openly expressed) by most all those who work at the farm — men and women of all ages who are on the autism spectrum or have a developmental disability.

Indeed, there are no ‘regulars’ at Prospect Meadow, only individuals with various talents who, it was thought, could certainly benefit from working outdoors, around animals, and as part of a diverse workforce handling various assignments that, like Mehler’s, are different every day — and also make $11 an hour while doing so.

And six years later, that theory has been validated — and then some.

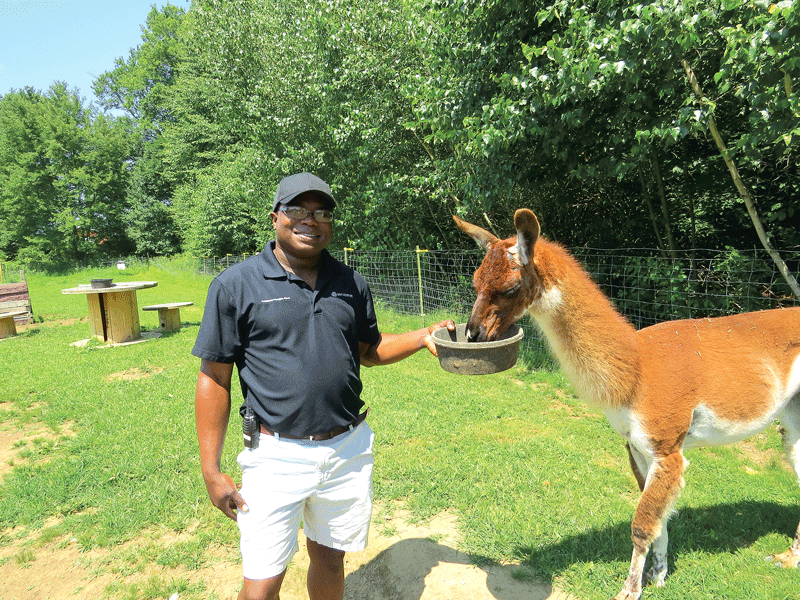

At top, farmhand Brittany Rawson tends to some of the parsley plants at Prospect Meadow Farm. Below, Shawn Robinson, director of the farm, with one of the resident llamas.

“When the facility was created in 2011, it was with the thinking that there would be a significant therapeutic effect to working outdoors and working with animals,” said Robinson. “That’s something I believed in before this started, but I didn’t quite know how powerful it was.

“One thing that we’ve seen is that people who were not successful in other work programs and had explosive behaviors, for example, would come here, and we just wouldn’t see those behaviors,” he went on. “And I have to credit a lot of it to the outdoors and the animals.”

Prospect Meadow is a multi-faceted operation with many moving parts. There are anywhere from 800 to 1,000 chickens on the property at any given time, and egg sales are a huge part of this business. Likewise, a shiitake-mushroom venture that started small and continues to grow provides those products to a host of area restaurants and stores.

There is also a landscaping component — crews will be sent out to handle a wide range of small residential and commercial jobs — as well as a catering operation managed out of the farmhouse. There are also plans in the works for both a feed store and a small café, separate operations that will provide employees with additional opportunities to interact with the public.

And, yes, the farm sells goats as well — to those, like Aerial, who want them as pets; to groups who need them for culinary offerings to be served at dinners and festivals; and to entrepreneurs who ‘employ’ them as “lawnmowers,” as Robinson called them.

But while Prospect Meadow might be gaining an identity from all of the above and especially the mushrooms, it is, at its core, a place of opportunity — employment-wise and personal-development-wise — for those who come here and don shirts with the farm’s logo, a rooster.

“We’re helping to increase these individuals’ skills and improve any sort of vocational deficiencies that may be identified, while also providing them with a real, paying job experience in a supportive environment,” Robinson explained, “with the hope that combining that support with that training could eventually lead to them being very successful in any career they pursue elsewhere.”

For this issue, BusinessWest visited Prospect Meadow to gain a full appreciation for the many aspects of this operation and the many ways it is cultivating growth, in every sense of that term.

An Idea Takes Root

When BusinessWest asked Robinson if he could pick up one of the chickens he was pointing out as he offered a tour of the farm and make it part of a picture, he replied with a confident “sure, no problem.”

The chickens, however, were not going along with the program.

Indeed, try as he might — and he tried several times — Robinson could not get both hands around any of these fast-moving fowl, and both hands are needed. So he suggested that the resident llamas might prove to be more willing subjects for a photo shoot.

Farm director Shawn Robinson (second from left) with, from left, farmhands Ana Tyson, Vicki Taft, and Justin Cabral.

Only, they weren’t. They were rather shy and kept retreating to their wooden home or the shaded area behind it; only bribery, in the form of a late-morning snack, seemed to help. Their recalcitrance gave Robinson an opportunity to shed some light on their presence at the farm (in some respects, they are where this story begins) and one of their primary assignments — protecting the chickens who live in the same general area on the 11-acre property.

“They use their legs to really fight, and other animals know that, and even their scent keeps some predators away … but they’ll go after other animals, too,” said Robinson, noting that, while llamas are certainly not indigenous to Hatfield, many chicken-loving animals that are, including coyotes, bobcats, and even the occasional bear, seem to know instinctively that messing with a llama is not a good career move.

But these long-legged animals have, as noted, another, far more important role at Prospect Meadow, that of being therapy of sorts for those who come to work there, and this takes Robinson back before the start of this decade and the genesis of Prospect Meadow.

A ServiceNet-operated residential program in Williamsburg for individuals with psychiatric issues was gifted some llamas, he explained, adding that the animals were having a recognizably positive impact on the residents, information that made its way back to ServiceNet director Sue Stubbs.

She was already aware of highly successful farm operations at the former Northampton State Hospital and other similar facilities, he said, and this knowledge, coupled with entreaties from the state for the development of more innovative vocational-services programs, spurred discussions about perhaps establishing such an operation.

However, the original vision was for a residential program for individuals with chronic mental illness, he continued, adding that Prospect Meadow eventually evolved into what it is today, a vocational program with 40 to 45 people working on the property on a any given day.

As for Robinson, he had no experience in the sector known as agribusiness, but that didn’t stop him from seeking out this career opportunity — or from thinking he had what it would really take to succeed in the role of director.

“I live in Hatfield and know lots of farmers, but certainly wasn’t an expert in that area,” he told BusinessWest. “But I was an expert in developing things and building things, so I was pretty confident that I could come up with a vision and develop this into something with the support of the ServiceNet leadership.”

And he was right; he’s built Prospect Meadow into that unique vocational-services program the state desired.

Individuals are referred to the program through the Mass. Department of Developmental Services (DDS) or through a school’s special-education department, and they often arrive after working in other settings.

Most of the farmhands are between the ages of 18 and 35, but there are some who are much older, and one individual recently retired after turning 65. They come from across Western Mass., but most live in Franklin and Hampshire counties.

Revenue to maintain the farm and its various facilities and pay some of the employees is generated in a number of ways, including the sale of eggs, mushrooms, and other products; the catering and landscaping services; and through community-supported agriculture (CSA) shares sold to area residents who, through those contributions, not only support the farm and its work, but fill their table with fresh produce.

Robinson said the farm operation takes on added significance today not only because it provides a different and in many ways better employment opportunity for those with various developmental disabilities, but because such opportunities are becoming increasingly harder to find.

Indeed, he said piecework job opportunities in area factories are fewer in number, and for a variety of reasons. And while some employers actively hire individuals with developmental disabilities, there is a recognized need for more landing spots.

Not a Garden-variety Business

Still, as noted, Prospect Meadow isn’t merely another a place of employment for those who come here. Because it is agribusiness, it provides opportunities daily that fall more in the category of ‘therapy’ than ‘work,’ although they are obviously both.

And this brought Robinson back to the subject of the animals, which are not exactly a profit center (with the exception of the chickens and their eggs), but provide payback of a far different kind.

“We keep the animals, even at a little bit of a loss, because they are able to make the farmhands more impactful in their other work,” he explained. “Having that 20 minutes to feed a goat in the morning or care for a rabbit makes them more focused when they’re dealing with the shiitake mushrooms or working in the garden.”

Indeed, the farmhands, when asked about what they enjoyed most about coming to work every day, typically started with the animals.

But they also spoke of the importance of the bigger picture, meaning being able to earn a better paycheck, learn a number of different skills, do something different every day, and work alongside others.

It was Justin Cabral, an energetic, extremely candid 26-year-old from Deerfield, who probably best summed up the many types of opportunities that the farm provides to individuals like him.

“I really love this job; it’s a real blessing,” he told BusinessWest, before going into some detail about all that he meant by that. And he started with some very practical matters.

“Before I came here, I was doing piecework at a different place,” he noted. “The pay wasn’t very good at all; I decided to leave and come here.”

We’re helping to increase these individuals’ skills … while also providing them with a real, paying job experience in a supportive environment.”

But then, he moved on to the many other elements in this equation — everything from gaining confidence from taking on various job assignments (including work to drill holes in logs with power tools) to learning how to work in teams, to overcoming fears, such as those involving animals.

“I drill holes in the shiitake logs, and I’ve become really good at it,” said Cabral, now in his second year at the farm. “And I used to be afraid of the chickens and the rabbits, and a lot of the animals here, but not anymore.

“I like everything … I like the egg collections, I like working out in the fields, I like feeding the animals, I like hanging out with my friends, and a lot more,” he said in conclusion. “It’s a great job, and there’s something here for everybody.”

Those sentiments were echoed by the many others we spoke with, and through their comments it became clear that Prospect Meadow provides much more than jobs.

Indeed, Robinson said the experience gained at the farm can open the doors for people in a variety of other settings, including other area farms, where individuals would work independent of state support.

Meanwhile, there are career paths at Prospect Meadow itself, he noted, adding that one can move — and some have — from farmhand to senior farmhand to ‘job coach,’ a level where the state is providing no funding for the individual, who has moved into what amounts to, as the name implies, a coaching position.

Scott Kingsley, 36, is a candidate for that job title, which would bring with it a host of new responsibilities, a pay increase, and benefits such as health insurance. He is currently working to help open the feed store and will work closely with those assigned to that operation.

“I like working with the animals, but I also like doing all kinds of different things,” said Kingsley, clutching the walkie-talkie that also comes with senior-farmhand status. “I guess what I like most is working with other people and helping them make money.”

Experts in Their Field

As he wrapped up his interview with BusinessWest, Cabral turned to Robinson, who asked him if he wanted to go back to his duties at the shiitake logs or hang in and listen to others as they offered comments.

“I’m not getting paid to sit here and talk,” he said with a voice that blended sarcasm and seriousness in equal doses. “I’ve got to go back to work.”

And he did just that, as the others would when it was their turn.

Most of them come here for four or five days a week, in all kinds of weather and at all times of year (this is a farm, after all). But none of them would prefer to be called a regular.

That term, as Mehler so eloquently noted, should be reserved for one of the buttons on a washing machine.

Here, there are only individual farmhands who together comprise a hard-working team that makes this farm a well-run business where there are growth opportunities — of every breed and variety.

And a place that can almost prompt Mehler to say she was a city girl.

George O’Brien can be reached at [email protected]