Region States Its Case for Expanded Rail

Progressive Platforms?

WMass asks for expanded rail service

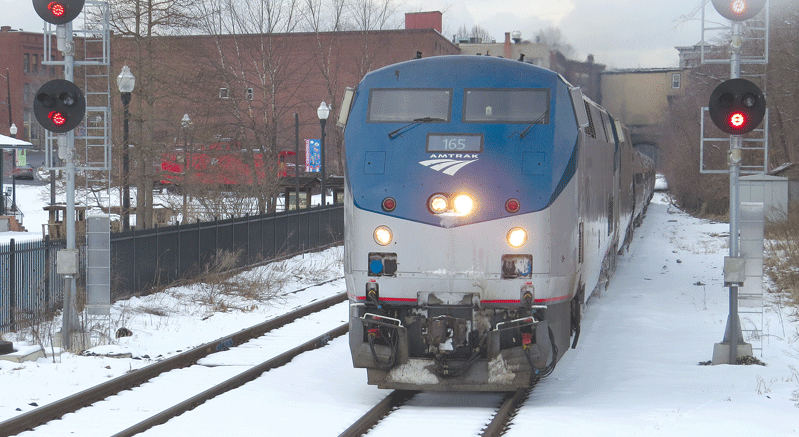

Since Amtrak’s Vermonter returned to the so-called Connecticut River Line just over a year ago, bringing back passenger rail service to Northampton, Holyoke, and Greenfield after a nearly 30-year hiatus, officials in those cities say the train has done what they hoped it would — enable people to make connections. But the single train per day has certainly limited the number of those connections, they note, which is why they’re calling for additional north-south service while also pressing the state to make long-dreamed-of plans for an east-west line that would connect Springfield with Worcester and Boston a reality.

Dave Almacy was in a really good mood.

And why not? Ohio Gov. John Kasich, for whom he was doing volunteer work leading up to, and then the day of, the New Hampshire primary, finished second in that closely watched contest, surprising pundits and energizing his candidacy while doing so.

“A definitive second,” offered Almacy, putting heavy stress on that adjective as he typed correspondences on his laptop while riding Amtrak’s Vermonter back to his home in Alexandria, Va. the day after the Granite State voted.

Almacy, a principal with Alexandria-based Engage, a Republican digital-strategy company, has mixed politics with technology for some time now — he was White House Internet director for George W. Bush from 2005 to 2007— and regularly takes the train north out of Washington, D.C.

Dave Almacy passed through Western Mass. on the Vermonter. Area officials want to attract riders who will get on and off in this region.

“I like the comfort. It’s a nice ride; I can be online and do my work, and you don’t have to worry about falling asleep at the wheel,” he joked, adding that he usually doesn’t get past Philadelphia or New York, cities where he has many clients. But his service to Kasich — “we were part of the ground game, going door to door, making phone calls, town halls, you name it” — took him to the northern stretches of the Vermonter and, for these particular remarks, the stretch between Springfield and Greenfield.

Indeed, the train was just south of Northampton, gliding on rails seemingly a few yards from the Connecticut River’s west bank, when he became one of several riders who spoke with BusinessWest about this Amtrak service and why they were using it.

That Northampton train platform became a line on the Vermonter schedule just over a year ago, joining Greenfield and (several months later) Holyoke as new stops for this service amid considerable fanfare from those communities’ elected officials and area economic-development leaders.

Actually, these are new/old stops for the Vermonter, which used to run along what’s known as the Connecticut River Line, or Conn River Line, until 1989, when the deteriorated condition of the track forced the service to move east and run from Springfield to Palmer to Amherst and then Vermont, a far more rural trek that bypassed several of the region’s most populous cities.

With seemingly one voice, area officials say the restored, now-quicker route — coupled with the new stops — is prompting more people like Almacy to grab a seat on the Vermonter, and adding new potency to comments about the seemingly vast potential of the train to bring people, vibrancy, and economic-development opportunities to those four cities and the region as a whole.

But those comments almost always come with, well, a ‘but.’ It’s usually followed by a reminder, twinged with lament, that the Vermonter — which connects Vermont with Washington, D.C. — runs but once a day; the southbound train passes through Springfield at 2:35 p.m., while the northbound version stops there at 3:15.

This schedule certainly limits the train’s potential when it comes to everything from economic-development potential to taking cars off the roads, said Northampton Mayor David Narkewicz, noting that anyone getting on the train in his city, and there are many who do just that, can’t return to it on a train for at least 24 hours — unless they get off in Springfield and take the northbound train a half-hour later.

“If you want to go to New York City and come back the same day, you can’t really do that,” he noted, adding that, while the train has in many ways energized his city, the current service is certainly limited in its impact.

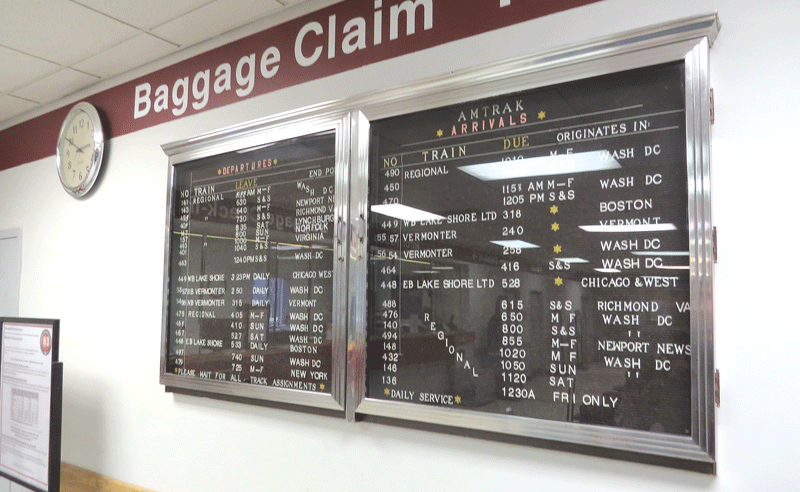

Tim Brennan, executive director of the Pioneer Valley Planning Commission, and perhaps the greatest champion of rail service in the region, agreed. He and the region’s mayors have taken their case to the state — more specifically, Transportation Secretary Stephanie Pollack. In a letter sent a few weeks ago, they seek help in two specific areas: first, with creation of a pilot program that would expand the north-south service to at least five trips a day, through the use of surplus, reconditioned MBTA locomotives and coaches, and second, with development of a business plan for the ongoing operation of the service beyond the initial pilot phase.

Rail proponents want to see more trains on the schedule at Springfield’s Union Station — and all the other stops in this region.

But as they pursue that option, officials are looking at another one. Indeed, as Connecticut invests heavily in the expansion of rail service between New Haven, Hartford, and Springfield, area officials have begun talks with officials in the Nutmeg State about a partnership that might see some of those trains continue past Springfield and on to Holyoke, Northampton, and Greenfield.

And, while maintaining a focus on the north-south aspect of rail service, area officials continue to press the case for an east-west route that would connect Springfield, Worcester, and Boston. That’s an expensive proposition, and it may not become reality for a decade or more, but proponents say it will be well worth the wait.

In general, those officials are hoping that rail service as a whole can do what the Vermonter does as it chugs north out of the Northampton station — pick up considerable speed.

Train of Thought

As she stood on the platform just outside the John W. Olver Transit Center in Greenfield, braving a stiff wind and passing snow squall, Carolynne O’Connell found a few people who could do what she couldn’t — speak from experience about riding the Vermonter.

And she had seemingly as many queries as BusinessWest did. ‘Which direction does the train come from?’ ‘How fast does it go?’ ‘How long are the stops?’ ‘How many people get on and off?’ — these were just some of the questions she was asked in rapid succession in the moments before the southbound train arrived, right on time, at 1:35 p.m.

Soon, O’Connell, an environmental health and safety specialist with Turners Falls-based Judd Wire, would be able to answer those questions herself. She and her husband were on their way to an annual conference of safety officials, this time in the Big Apple.

She’s been to similar gatherings in recent years, in Milwaukee, Los Angeles, Boston, and other cities where the method of transportation was seemingly obvious. Not so with Manhattan, she explained, adding that several options were considered and mostly discounted for one reason or another.

Flying was deemed rather expensive, while driving seemed impractical given traffic and the cost of parking, she said, adding that some research introduced her to the Vermonter, which was now quite accessible from her home in Orange, roughly 15 miles east of Greenfield, and affordable — $126 per person for a round-trip ticket.

Thus, she became one of a growing number of individuals choosing that train and, in many ways, providing additional motivation for that letter from area mayors to Secretary Pollack.

Indeed, O’Connell is the kind of passenger area officials had in mind when they pressed for the new/old stops for the Vermonter. Or one of the kinds of passengers, to be more precise — individuals across several categories who get on or off the train in Western Mass.instead of merely traveling through it on their way to somewhere else, like Almacy and many others BusinessWest encountered on this Wednesday afternoon.

Other categories include area college students commuting between home and their chosen campus; professionals with clients in Hartford, New York, Philadelphia, Baltimore, Washington, or any of the other stops the Vermonter makes; individuals seeking another option for getting to a ski resort; and people visiting friends and relatives north and south of the Pioneer Valley.

And then, there are potential new categories of riders — including those who might choose to live in a particular area because it’s near a convenient rail line, and also those who might want to visit Northampton for dinner and a show and then head back home.

In each case, the categories — real and potential — are limited by that aforementioned ‘but,’ the one train a day. That’s why Brennan and the area’s mayors, while happy for that one train, are making their case for expanded service loud and clear.

The new rail platform in Greenfield is one of several built with the anticipation that train service will be a game-changer in the region.

Narkewicz noted that Northampton has easily seen the most ridership among the cities that have again become lines on the Vermonter schedule. He’s ridden the train many times himself, and has encountered area college students heading north and south, as well as students from this area returning to various campuses; musicians traveling to New York for performances; and residents heading to various stops along the line for business or pleasure.

“It’s really a broad mix, and it’s very encouraging to see all these people taking the train,” he told BusinessWest, adding quickly that there would be far more potential for people to get both on and off the train in Paradise City if it came through more often.

“You could have people looking to see someone playing at the Calvin Theatre, or take in a play at the Academy of Music, or see an exhibit at the Smith College art gallery — and take the train to do that,” he explained. “We already are a destination for tourism, and this could be another access mode for people.”

And if the service were regular enough, there might be a much different train of thought — literally, said the mayor.

“If there is enough frequency of trains, you may have people getting off in Northampton and saying, ‘this is a really beautiful city … this would be a great place to live — it’s on a train route, and I can get to Springfield, Hartford, New Haven, or wherever by train; I can live here,’” he said.

Connecting the Dots

Marcos Marrero, director of Planning & Economic Development in Holyoke, said the city built its $3.2 million Depot Square Railroad Station with what he called realistic expectations for its use.

For the most part, he added, they are being realized, with fewer than a dozen people, on average, getting on or off the Vermonter each day in the Paper City.

“We projected that there would not be a lot of riders starting out, which is why we didn’t build a huge parking lot for it,” he explained, adding that the unwritten ambition is to have to construct a bigger one someday, preferably soon.

Marrero said he’s witnessed people getting on the train to go skiing, travel to business appointments, or visit relatives in Connecticut and New York — something they could do previously by train, but only by getting to Springfield first — with more usage on or just before a weekend.

But Holyoke didn’t build that train platform — nor do its officials continue to talk glowingly about its potential to help the city attract residents and businesses — with one train a day in mind.

The focus, as it is in other communities, is on the bigger picture, said Marrero, noting that this means both more north-south travel and, eventually, hopefully, an east-west route.

“The promise of rail is attractive,” he explained. “Having the train station is akin to building an airport … that’s the start, and then you work to populate it with more air service. The train service is similar to that — now we have to work on expanding it.”

Like Brennan and others, Marrero said the train — even one that goes through once a day — allows people to make connections in other Western Mass. communities as well as other cities and towns on the route, especially those to the south. More trains equates to more connections, which is why, throughout history, communities with rail stops have generally fared better than those that lack them, when it comes to being both a destination and a place where people want to live and conduct business.

“For our strategy in the downtown of creating new businesses, homegrown businesses, people from the outside who want to start new ventures, while also creating more opportunities for living here, it’s important to have those connections,” he explained. “They can be with businesses in Springfield or job opportunities in Hartford.”

Narkewicz agreed. “Any time you can make the world a little bit smaller in terms of connecting us to the Valley and the rest of the north-south corridor, that’s important.”

It is the desire to create such connections that prompted a return to the Conn River Line for the Vermonter and, only a few months after it was back in service, a call for more trains.

Just when, and even if, Holyoke will need to build a bigger parking lot is hard to gauge, but Brennan believes there could be some progress by the end of this year or early next. Indeed, expansion of the New Haven-Hartford-Springfield service, which will bring another 12 trains a day into the City of Homes, should be completed by year’s end.

Talks are underway with the Connecticut Department of Transportation about taking some of those trains farther north, and the matter is being taken under advisement, he noted.

“They’re interested in doing that. They would want us to pay our fair share, but they are keeping that option open.”

The other option for expanding north-south service — deploying surplus MBTA equipment on that route — was promoted in a Jan. 29 letter to Pollack, which seeks creation of a pilot program that will reveal potential usage.

Obtaining that MBTA equipment is the key, Brennan told BusinessWest, adding that, if and when it can be earmarked and refurbished, a request for proposals will be submitted for those seeking to operate a service several times a day — preferably two runs in the morning and two more in the evening, on top of the Vermonter.

He expects there will be response to such an RFP.

“There would likely be a half-dozen or so operators that would bid on it,” he projected, adding that Amtrak and Pan Am Railways, which moves freight along the Connecticut River Line, could be among those bidders.

Track Meets

Such expansion of rail service, both north-south and (hopefully) east-west, will enable the train to become more than what it is now — essentially another means of getting from here to there, said Brennan.

As he elaborated, he summoned the phrase “transit-oriented development,” terminology that essentially speaks for itself — although Brennan did offer an explanation.

“When you’re able to offer passenger rail service, the places where the train stops tend to become catalysts for economic development within a quarter-mile to a half-mile of the station,” he noted. “It’s like you create a hot spot for development in that area where you can walk to the station — for example, if you get out of Springfield’s Union Station and walk to your office, or get off the platform in Northampton and walk to Smith College.”

Creating such hot spots is really what the push for rail service is all about, he went on.

“We’re trying to get the level of service up so that those communities where the train is going can generate the full rate of return on investment,” he told BusinessWest, referring to both the costs the communities have incurred and the money pumped into rail by the state.

Hopefully, there will be additional investments, in the north-south line, but especially east-west service farther down the line, as they say in this business.

Indeed, it is the potential to connect Springfield with Worcester and Boston via rail that has Springfield Mayor Domenic Sarno particularly intrigued about transit-oriented development.

Carolynne O’Connell, who took the train from Greenfield to the Big Apple for a conference, represents the type of rider area officials had in mind when they lobbied for an extension of north-south rail service.

He noted that the potential for people to be able to work in Boston, Cambridge, or Worcester and live in Springfield — something that would become much more feasible with fast, reliable, east-west train service — could be one of many sources of economic development in the future.

“An east-west service makes sense with everything we’re doing here in the city, including Union Station, MGM, efforts to generate entrepreneurship, creating market-rate housing such as Silverbrook Lofts, and more,” he explained. “The cost of living out here, whether it’s for residential or running a business, is much more palatable than it is in the eastern part of the state.

“It will take a huge investment, and for that reason some people say this is all pie in the sky,” the mayor went on. “But to have an east-west service that would run all the way to the Berkshires makes a lot of sense.”

Brennan agreed, noting that, if expanded rail service becomes reality, this region, and especially cities like Springfield, Northampton, and Holyoke, could benefit from what he called “re-urbanizing,” a reverse of what occurred 40 years ago, when people and businesses moved out of cities.

“There are two segments of the population that are increasingly interested in living in denser urban centers where they don’t need a car,” he explained. “These are seniors, retirees, and also young workers.

“Young people often don’t have a car and don’t want a car,” he went on. “But they want mobility, so the train is very attractive to them; they’ll live and work in an area if you offer them some type of rail alternative. Conversely, seniors, while they’re healthier, aren’t as interested in maintaining a big home and a lawn, and they’re finding cities more attractive.”

The region can be part of this movement, which is national in scope, said Brennan, but not if there’s only one train a day going in both directions, and not without east-west service.

The Last Stop

Sarah Beers is a costume designer from Queens. As she rode the Vermonter back home from Marlboro College — a liberal-arts school located in a town of that same name just west of Brattleboro, where she teaches three times a semester — she talked of this train service in mostly glowing terms.

“But it could be a little quieter … and definitely faster,” she told BusinessWest, adding that she wishes Amtrak could somehow slice at least an hour off the five-and-a-half-hour trek to Penn Station.

Western Mass. officials have another wish when it comes to the train — they just want more of it.

Getting those additional runs, they say, will take rail service from being a convenient transportation option to being a platform for growth and progress — both literally and figuratively.

Meanwhile, such an expansion will allow them to stop talking about what rail service could be and start discussing what it is.

George O’Brien can be reached at [email protected].