Suit Up Springfield Will Do More Than Help Men Look the Part

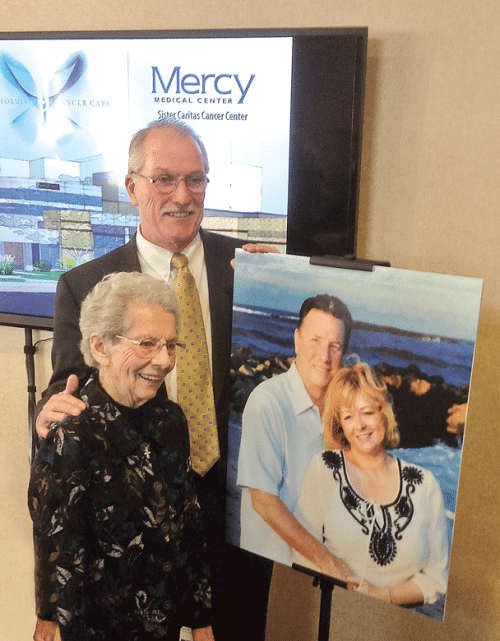

From left, Jeremy Casey, Justin Roberts, and Nico Santaniello, three members of the board of mentors working to get Suit Up Springfield off the ground.

Justin Roberts acknowledged that not everyone wears a suit, or even a tie, in this age when casual Friday has seemingly given way to casual every day.

But he added quickly that many still do command a certain bit of respect for their choice of attire, and derive some all-important confidence from it as well. Meanwhile, there are many instances — especially the job interview — where formal wear remains a must, even for those who don’t have any in their closets.

And this is why Roberts, Development officer at American International College, partnered with several other young professionals across the region to create an organization called Suit Up Springfield.

As the name implies, this nonprofit’s mission is to put suits — and also ties, shirts, dress socks, and shoes, if necessary — in the hands of those who need them, similar to the way Dress for Success provides office-appropriate clothing, as well as mentoring and other forms of support for women looking to advance.

Indeed, like that organization, Suit Up Springfield, now barely two months old, plans to do much more than help men look the part and dress professionally. It will show them how to tie the ties they pick off the rack and how and when to button a suit, for starters, said Roberts, who is partial to bowties himself, and then it will drive home the point that simply wearing the right clothes isn’t enough to get a job — or succeed with one’s goals for life and work.

“The suit is a starting place,” said Roberts, adding that the agency, through its so-called ‘board of mentors,’ also plans to provide everything from interviewing tips to various levels of mentoring to advice on how to give back to the community and encouragement to do so.

“When you walk into a room wearing a suit, you gain the respect of the people in that room,” said Jeremy Casey, vice president of the board and a vice president with First Niagara Bank. “But to succeed, you need much more than the suit.”

At present, Suit Up Springfield has neither a location from which to carry out its mission nor a firm set of procedures on how to collect and dispense clothing — the board is working diligently on both assignments. But what it does have is momentum, and lots of it.

Ever since Roberts began finalizing his concept and announcing the group’s intentions through a host of social-media vehicles, the response — from within the city but also well outside it — has been nothing short of phenomenal, and also inspirational, giving those involved more hard evidence that they are meeting a recognized need.

This response has manifested itself in everything from pledges to donate clothing to requests about how and in what ways to volunteer support, to inquiries from groups and individuals about how to get similar programs off the ground in other cities.

“We put up a Facebook page, and within hours we had hundreds of likes,” said Casey. “And we had all these people reaching out, saying, ‘how can we help? We want to donate suits; we want to donate shirts,’ until it grew virally out of control, to the point where we have more than 500 e-mails in a queue right now saying, ‘we have multiple suits we want to donate.’

“The most incredible aspect of this month-and-a-half-long journey has been the number of people who have come out and said they want to help,” he went on. “I know from working on a lot of boards that many nonprofits solicit for help. We’re not soliciting for help, but more people are saying, ‘how can we get involved?’ which is extremely refreshing and shows the vibrance of this community and the need for this organization.”

Roberts agreed, and said his inbox and voice mail have been flooded with inquiries from individuals in other communities looking to emulate the model they’re creating or applaud the group’s efforts.

“I’ve been approached by people in Boston and Providence about this,” he said. “Within the first week of starting this, I got a call from every politician in Western Mass. as well some of the most powerful CEOs in the region. The response has been incredible.”

For this issue, BusinessWest takes an in-depth look at this fledgling nonprofit and how it intends to carry out its unique but all-important mission.

Knot Withstanding

Retracing the steps that led to the creation of Suit Up Springfield, Casey said the original idea tossed around by some of those involved was to meet a recognized need for formalwear by taking referred individuals to thrift shops and other outlets and purchasing items for them.

But organizers quickly determined that the emerging nonprofit could — and should — be much more, with a system for collecting and dispensing thousands of items, and a mission that went beyond simply outfitting those who might need a 42-long and matching tie for a job interview or to move their career forward.

But organizers quickly determined that the emerging nonprofit could — and should — be much more, with a system for collecting and dispensing thousands of items, and a mission that went beyond simply outfitting those who might need a 42-long and matching tie for a job interview or to move their career forward.

Early on in the discussions, Casey noted, it became clear that a mentoring component should be part of the equation.

“The suit is a catalyst to get them in the door,” he told BusinessWest. “If they get a suit from us, they have to go through our mentorship program, which teaches about civic engagement, professionalism, giving back to the community, and the things that happen to the community when you do those things.”

The Dress for Success program, which now has 125 affiliates in the U.S., Australia, Canada, New Zealand, the Netherlands, the United Kingdom, and other countries, serves as an attractive model to emulate, said Casey, adding that research revealed a lack of comparable agencies devoted to meeting the needs of men — as well as a desire to create some, as those e-mails suggested.

But while offering advice and inspiration to those in other cities looking to borrow this concept, Suit Up Springfield’s immediate goals are to create an infrastructure and start to collect the 1,200 to 1,500 suits that Casey believes have already been pledged, formally and informally.

Moving forward, Suit Up Springfield intends to move quickly to set up a storefront in or near downtown Springfield — the goal is the end of this year — and also finalize procedures for building an inventory of donated attire and then dispensing it, create a network for fielding referrals, and even forge a partnership with a dry cleaner, said Roberts, adding that the overarching goal is to create a sustainable model.

A changing commercial real-estate climate — one of many byproducts of the official start of the casino era in Springfield — has complicated the search for a location, but organizers remain confident they can find something, well, suitable, and in good order.

“If we were doing this a year ago, it would have been a lot easier, but the casino vote has certainly changed things,” said Casey, adding that, while downtown real estate is becoming an increasingly hot commodity, organizers are confident they can secure the space and visibility they require.

As for a process for accepting donations, organizers said they will look to create options — from individuals dropping off new or almost-new items at the agency’s eventual location (probably on a designated day or days each month) to area companies and nonprofits staging what Roberts called “suit drives” at their locations.

And organizers believe there will be plenty of clothing to collect.

They say they’ve already heard (mostly via e-mail) from college presidents, company CEOs, and a host of professionals, from lawyers to bankers to accountants, saying they are ready and willing to donate items from their closets.

Niko Santaniello, treasurer of the board and a financial adviser with Northwestern Mutual, said there are a number of factors — from changing styles to the more informal nature of business dress, to the growing ranks of retiring Baby Boomers who have far less need for suits and ties — that will help keep the racks filled in the years to come.

But the biggest factor, he told BusinessWest, is a desire to help the fledgling organization carry out its multi-faceted mission, meaning elements such as mentoring and helping individuals get involved in the community — and stay involved.

“One of the things we’ve discussed as a board is how to keep individuals we serve involved in the community,” he said, “whether it’s from volunteering at our storefront, joining the Young Professional Society, volunteering with a nonprofit, mentoring others, or showing guys how to tie a tie. We want them to stay involved.”

Casey agreed, and predicted that, if the organization develops as planned, its mission will benefit not only the individuals it serves, but the business community and the region as a whole.

“What business wouldn’t want someone else to do free training for a new employee?” he asked rhetorically. “Individuals are getting trained on civic engagement, which is something that 99% of organizations are passionate about, and also on professionalism, which is something that every business teaches right now, because they want to make sure their customers, or end users, are satisfied with the product or service they’re providing.”

A Natural Fit

As they talked with BusinessWest, Roberts, Casey, and Santaniello paused at one point to reference their brightly colored and wildly patterned Happy Socks, the Swedish product that has become a must-have accessory for young professionals.

They did so to illustrate how styles change and how important it can be to have the right look — whatever it is and for however long it remains in vogue.

Some things don’t change, though, they added quickly, noting that a suit always makes a statement, and sometimes it can help open a door.

Suit Up Springfield was created to not only help an individual find an open door, but give them the confidence to walk through it.

In the process of doing so, its organizers believe it will succeed with that mission of building opportunities.

For more information on the agency, visit www.suitupspringfield.com.

George O’Brien can be reached at [email protected]