The Academy of Music Has Seen Its Share of Cultural Shifts

Behind the Curtain

Debra J’Anthony says the Academy of Music’s history speaks to the commit-ment of its community to the arts over the decades.

During a decade of renovations at Northampton’s Academy of Music, few proved more surprising than the sailcloth canvas that lined the theater’s century-old curtain.

“We’ve put a lot of attention on maintaining the historic integrity of this building,” said Debra J’Anthony, the facility’s executive director since 2008. “There’s a lot of mindfulness and thought in this space. We’ve tried to get state-of-the-art technical equipment and at the same time preserve the historical integrity of the space.”

The sailcloth, as it turned out, was actually a massive landscape painting of nearby Paradise Pond. It was restored by a Vermont company called Curtains Without Borders, which specializes in preserving historic stage scenery, and now hangs high in the Academy’s rafters upstage.

As historical fragments go, it’s actually a relatively minor one in the 127-year-old facility’s rich story. Edward H.R. Lyman opened the theater in 1891 as a building “suitable for lectures, concerts, opera, and drama for the public good.” Remarkably, the Academy’s priorities have changed very little since then.

“There has been a mix of activity, but depending on the year, there has been a weight toward one medium or another,” J’Anthony said. “In the beginning, it was just performing arts and lectures; then, starting in the 1930s, it was weighted more heavily toward film. We actually had a film distributor out of Boston that leased the building for about 10 years, so the Academy actually did quite well during the Depression because they had a renter in here.”

During the first few years of J’Anthony’s tenure, she led another transition, from what was largely a first-run film house, with occasional live performances, to what it is today, a performing-arts venue that hosts scores of shows — national touring acts, presentations by local companies, and sometimes the Academy’s own productions — throughout the year.

Efforts to fill that calendar have been boosted by a series of renovations to the theater, from shoring up the envelope of the building — including new roofing and replacement of leaky windows and doors — to launching the organization’s first-ever capital campaign to pay for a major renovation of the theater space itself.

“There were seats upstairs dating from 1947, and there were seats downstairs that were bought used during the 1960s,” J’Anthony said, noting that the Academy worked with Thomas Douglas Architects to re-establish a period look, and received a Preservation Award from the Massachusetts Historical Commission for its efforts. “We’re hoping to continue to renovate, finish the renovations in the hall, then go out into the lobby areas. We’re hoping to receive some Community Preservation Act funds soon to complete the opera boxes and add architectural lighting.”

In addition, because the Academy had mainly been a film house during the tenure of Duane Robinson, who ran it for more than 35 years before J’Anthony’s arrival, there wasn’t much modern theatrical equipment on hand. So the theater recently installed a new sound system, replaced some outdated theatrical lighting with LED lighting, and installed new flooring for theatrical productions.

Those efforts have helped make the Academy of Music a more attractive venue for national touring acts. The theater’s relationship with Signature Sounds led to a relationship with Dan Smalls Presents, which represents many of the the national touring bands that come through Northampton.

“We’ve got the attention of AEG and Live Nation as well,” she added. “The model is definitely working. There’s usually somebody in here most days. We have a wide range of offerings, from hip hop to ballet, from opera to Americana music, film, comedy, dramas, musicals — so there’s something for everybody.”

Rich History

Looking back to the beginning, Lyman had the foresight to purchase a lot of land on Main Street that would eventually be one of Northampton’s main crossroads. Working with well-known architect William Brocklesby of Hartford, Lyman had the two-story Academy built for $100,000, plus $25,000 for interior decoration and equipment.

It opened in 1891 with a sold-out concert featuring four solo artists backed by the Boston Orchestra. But Lyman’s fondest interest, opera, never really caught on at the center.

He eventually gifted the theater to the city, and it remains the only municipally owned theater in the U.S. — and a largely self-sufficient one. Aside from occasional help from the city to make needed repairs, the facility has never had a line item on the Northampton budget, surviving on box office and donations.

Throughout its first 15 years, the Academy became a popular stop for drama troupes and traveling road shows, attracting some of the top talent of the day, including Sarah Bernhardt and Ethel Barrymore.

With the economy shifting and top acts harder to come by, the Academy’s trustees went in a different direction in 1912, establishing a resident dramatic company, the Northampton Players. Although their shows were popular, especially with the Smith College crowd, they didn’t make enough money, and the group was disbanded a few years later. Various efforts to revive resident theater were reattempted throughout the 1920s, but none of the companies survived for long.

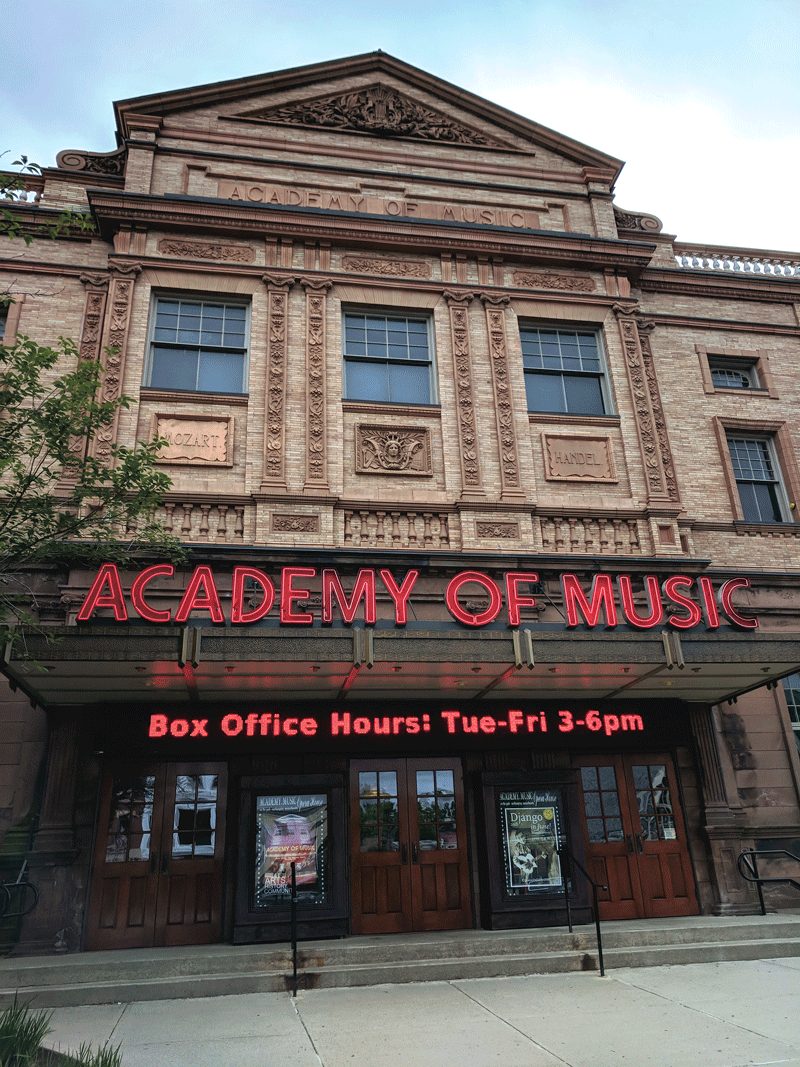

Opened in 1891, the Academy of Music’s iconic building has been a prominent fixture at one of Northampton’s busiest intersections.

That era saw visits to the theater by the likes of Frank Morgan and William Powell, among other names who later made the transition into motion pictures — which would be the Academy’s direction as well.

In fact, it had presented its first moving picture in 1898, shortly after the ‘projectiscope’ technology was introduced to the world. By 1921, the Academy was showing films three times a week, and by 1930, the facility was run primarily as a moviehouse. The trustees made the sea change permanent in 1943 by spending $40,000 to modernize the theater.

During that period, the Academy had a falling-out with the film distributor who leased the building through the 1930s, J’Anthony noted. When theater manager Frank Shaughnessy was called to military service, he recommended that his clerk, Mildred Walker, who had been working alongside him for 16 years, mind the shop while he was serving in the military.

“And the board agreed,” she went on. “She was a local resident and known entity to the organization. However, the film distributors were upset that the board would allow a woman to run the theater. So they took the Academy to court — and the Academy lost. That’s why their relationship discontinued; they didn’t re-up the lease.”

Walker, in the meantime, proposed a new governance model whereby the board would run the building, but would hire a manager. “And she recommended herself,” J’Anthony said. “They agreed to her governance model; however, they hired Clifford Boyd to run the theater.” Decades later, in 2014, following the spate of renovations, the Academy commissioned and presented a new work, Nobody’s Girl, that told Walker’s story.

Boyd, a veteran of the theater industry, oversaw a shift at the Academy of Music to live performing arts. Later, under Robinson’s tenure, from 1970 through the early part of the new millennium, the facility reverted to mostly film, as well as undergoing a series of needed renovations in the ’70s and ’80s. But that business model, too, was set to change.

“Film distribution changed in the 1980s with the rise of the megaplex,” J’Anthony said, “so one-screen venues across the nation had to make changes. Either they turned into megaplexes or became performing-arts centers.” The latter, of course, continues to be the Academy’s path today.

Into the Future

When J’Anthony came on board in 2008, the Academy was primarily renting the hall to community-based organizations, but soon established a series of resident companies and partners that supply regular programming.

“However, we needed to look at producing our own shows during the recession, when many of the opera companies folded, and so we started producing our own shows here, which led us into youth programs.”

Those include three sessions of summer musical theater workshops for ages 7 to 14, and in January, the Academy conducts rehearsals for a youth production in March.

“In addition, we have been producing plays,” she continued. “We started focusing on women’s works — being in Northampton, and being connected to Smith College, that just made sense. And we’ve been adding more presentations and productions each year.”

The theater, with a capacity of just over 800, welcomes some 60,000 visitors each year for performances, so it’s still a cultural force in the city after so many decades of change.

“Certainly, there’s a sense of place within this community for the Academy of Music. It is a place of gathering, of sharing ideas,” J’Anthony said, adding that its blend of big-name attractions and community-based productions make for an intriguing mix. “Somebody can be out in the audience and see a national touring show one night and be on stage the next night.”

That said, the Academy also strives to be sensitive to its market, she noted. “We do things that are a little more edgy than other venues. We keep our ear to the ground in regard to the values of our community, what is relevant to them, and making sure we bring art forms that can engage them in further discussions and offer new perspectives.

“A building like this is a valued asset, and it takes a large community to maintain this building and the programming we have here,” she went on. “So we’ll keep working with the city, the state, and Community Preservation Act funds, as well as individual contributions, to keep this space going. It’s all hands on deck.”

Joseph Bednar can be reached at [email protected]