The Big Picture

MASS MoCA Fills In the Wide Canvas of Contemporary Art

Joe Thompson says MASS MoCA’s constantly changing installations and inclusion of performing arts make it more vibrant than a static art museum.

And with that, as if on cue, the sounds of people banging on metal drums, accompanied by a woman singing opera, could be heard from the floor below.

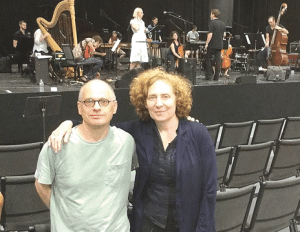

This was the New York City-based, multi-faceted classical-music organization Bang on a Can, which, according to its Web site, is “creating an international community dedicated to innovative music, wherever it is found.” With that mission in mind, the group, led by composers and founders Julia Wolfe, David Lang, and Michael Gordon, sought out MASS MoCA as the home for a summer educational and residency program for fellows and students in all forms of music.

The 18-day festival, which concluded on July 28, is sometimes called ‘Banglewood,’ in reference to the nearby, and much more traditional, Tanglewood Music Festival in Lenox. It is is dedicated, said the group, “entirely to adventurous contemporary music; we will write it, we will perform it, we will think about it, and we will talk about it.”

And for all that, the museum in North Adams, created out of several old mills that were part of the Sprague Electric complex, has become a venue Wolfe called both supportive and inspiring.

“MASS MoCA is a gold mine of support and atmosphere,” Wolfe told BusinessWest, “and this program, with all the surrounding art, allows for students to create and perform as colleagues, side by side with seasoned performers. It gets music into art spaces.”

Creation of this powerful learning environment is one of many ways to qualify and quantify the success MASS MoCA has recorded since opening in the summer of 1999, said Thompson, the museum’s director, adding that others include solid attendance figures (130,000 last year, a new record), a growing endowment (currently $14.5 million), and a large number of return visitors, a statistic that lies at the heart of the facility’s current operating philosophy.

Indeed, instead of a static museum dedicated to contemporary art, MASS MoCA is an ever-changing institution that showcases paintings in canvases, but also film, video, sculpture, and, yes, music.

“The farther away you get from North Adams, the more people think of MASS MoCA as a museum; the closer you get to North Adams, the more people think of MASS MoCA as the place where they see theater or dance events,” said Thompson, adding that this range of descriptions speaks to just how the museum has become different things to different people.

For this issue and its focus on the region’s tourism industry, BusinessWest looks at how MASS MoCA continues to grow and evolve while finding new ways to meet its two main goals: to provide a state-of-the-art (and arts) platform for contemporary works of all kinds, and create jobs in a corner of the state that needs some.

Exhibiting Determination

It’s called Solid Sound.

That’s the name that was given to a three-day music festival launched by MASS MoCA administrators in 2010, featuring Wilco, the American alternative-rock band based in Chicago.

Thompson said he and others were confident that Wilco and its opening acts would draw a good turnout, but they actually got a lot more than they bargained for — and more than the town was prepared for. More than 5,000 fans descended on North Adams, filling every available parking space and prompting restaurants to run out of food. Thompson and city officials who helped stage the event feared that litter would be scattered throughout downtown the morning after the event wound down.

“But all throughout downtown, all we saw were full garbage cans and neatly stacked cups and lined-up bottles — by recyclable type — next to each can,” said Thompson with a laugh. “It’s due to the type of engaged and environmentally conscious following that Wilco has.”

And this is, by and large, the same type of audience that is attracted to contemporary, or new, art, he continued, adding that the museum draws more than 120,000 visitors per year — a tribute, he believes, to an operating philosophy that he and others involved with this project agreed upon as they raised and then spent more than $31 million to convert portions of the Sprague complex into one of the largest (area-wise) contemporary-art museums in the world.

Going back to the early and mid-1990s, Thompson said he slowly grew away from his original, and firmly rooted, belief in the concept of a museum with large, fixed installations devoted to pared-down ‘minimal art’ of the ’70s and ’80s. While he admits they look great in the generous, rough-hewn spaces afforded by mill buildings, and don’t require fancy climate control, he came to think that static art offered far too limited a vision — perhaps a dangerously constrained one.

“Many people who shared my love of new art worried out loud whether visitors would make repeat visits to a permanent, fixed installation,” he explained. “That question — ‘would people come twice?’ — that was a tough question, and led me to think that a program of changing, shorter-term exhibitions might be a more engaging way to begin.

“As artists had become increasingly fluid in the way they work, with art-making practices that cross from sculpture to set design to video and film,” he continued, “it became clear that an institution that was to be truly responsive to the needs and trajectories of new art had to incorporate the performing arts as well.”

In a nutshell, the past 13 years of operation have essentially proven Thompson and others right in their thinking. The museum has changed exhibits regularly and hosted a broad mix of media — as evidenced by Solid Sound, Banglewood, and other projects and events — and visitors have come back repeatedly.

Creative Economy

The list of current and upcoming exhibits speaks volumes about the diversity created at MASS MoCA and the ability to present a different museum every time visitors venture to North Adams.

There’s “Oh, Canada” (through next April), the largest survey of contemporary Canadian art produced outside of Canada. It features the work of more than 60 artists who hail from every province and nearly every territory. There also “Invisible Cities,” showing through next February. Titled after Italo Calvino’s book — which imagines Marco Polo’s vivid descriptions of numerous cities of a fading era to Kublai Kahn — it features the work of 10 diverse artists who reimagine urban landscapes both familiar and fantastical.

Meanwhile, “Stanford Biggers: The Cartographer’s Conundrum” is a major multi-disciplinary installation by New York-based artist Stanford Biggers, and was inspired by the work of his cousin, the late artist, scholar, and Afro-futurist John Biggers.

And then there’s “Sol LeWitt; A Wall Drawing Retrospective, which is an ongoing, semi-permanent display that is the one notable exception to Thompson’s basic operating strategy of changing exhibits. It includes 105 large wall drawings — many would use the term murals — created by artist Sol LeWitt, who is considered by many in the art world to be the most influential conceptual artist of our time.

It is due to the sheer size of LeWitt’s large-scale art, some of it measuring more than 30 feet long by eight feet or more in height, that MASS MoCA was considered an ideal home for these works. Thompson told BusinessWest that a call early in 2003 from Yale University Art Gallery Director Jock Reynolds set in motion the process for bringing LeWitt’s art to North Adams, but first he had to be sold on a permanent display.

As Thompson explains it, Reynolds and LeWitt needed the space to construct LeWitt’s legacy (the artist never lived to see the unveiling in 2007) and focused on MASS MoCA because no other museum in the Northeast could dedicate tens of thousands of square feet of space to such large works. Thompson said the collaboration between Yale, the Williams College Museum of Art, and MASS MoCA resulted in a stunning “museum within a museum,” as he called it, on three floors, totaling 30,000 square feet.

“As much as we love our changing program, and you’re only as good as your last show, this was a rule-breaker for us,” Thompson said. “Suddenly, we had this beautiful milestone installation of Sol LeWitt’s, and it’s super-high-quality, it’s colorful, full of detail, and it just leaves you smiling — it just makes you feel good.”

It was a turning point for Thompson. “It made me think that the ideal museum is one that has both a core, permanent collection, but also lots of room for change; you want masterpieces that people return to over and over again, but you also want a vibrant roster of changing exhibitions that trigger the return visit. Sol LeWitt helped us see that.”

Broad Strokes

While MASS MoCA hasn’t yet matched its goal for creating 600 jobs, it has succeeded in contributing to the economic development of North Adams and the Berkshires in general, said Thompson, adding that it has become a day-tripping destination while also filling some hotel rooms as well.

Meanwhile, it has become that proverbial ‘different sort of venue’ that has attracted the likes of Bang on a Can, Wilco, and visitors who want to experience the full range of new art.

Perhaps David Lang summed it up best when he said that, because the museum, perceptions of North Adams have changed.

“Before, it was always a place you could visit,” he said. “Now, it’s a place you have to visit.”

Elizabeth Taras can be reached at [email protected]