The Rust of the Story

Artist’s Work Brings Heavy Metal to Downtown Springfield

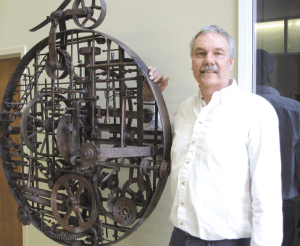

It’s called “Linear and Out the Other.”That name says a little about the large piece of sculpture — a collection of interconnected discarded metal parts, tools, and kitchenware ranging from gears to springs to an old egg beater — but much more about the artist.

Indeed, James Kitchen is a devotee of puns — each one worse than the next — as well as a lover of history and a fervent collector of such old junk, or what he tells his supporting wife is “inventory.”

And he names his pieces after what he sees in them, and imagines what others might see as well. There’s a horse-like creation titled “Why the Long Face?” A large-beaked, bird-like image that looks somewhat like a pelican, but not entirely, is called “Pelican’t.” Then, there’s what looks like a bouquet of flowers fashioned from pitchfork tines with large metal nuts welded onto the sharp ends. The name? Get ready to groan … “Steel Life.”

“I’ve learned that humor is your most important weapon in life — it ultimately gets you through most things,” Kitchen explained while discussing the whimsical titles. “A lot of the time, I make something, and then the name usually just happens. What I’ve found is that, if I don’t put a name on something, people are more prone to say, ‘I don’t get it, what is it?’ If I do, then they understand.”

As he looks at “Linear and Out the Other,” which he described as “busy and intense,” and has pieces welded in a grid-like fashion, Kitchen says he can see everything from “Springfield politics,” to a road map; from something exemplifying molecular science to the connections he’s made in the city since arriving on the scene a few months ago.

“I’m a voracious reader, and I’ve read about quantum physics,” he explained. “When you think about [Danish physicist] Niels Bohr, and how he and others talked about how everything’s random, and multiverses, and string theory … I made this thinking about all the interconnectedness of things, the entanglements. Life is like that; downtown Springfield is like that, with all the connections I’ve made.”

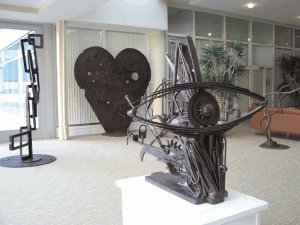

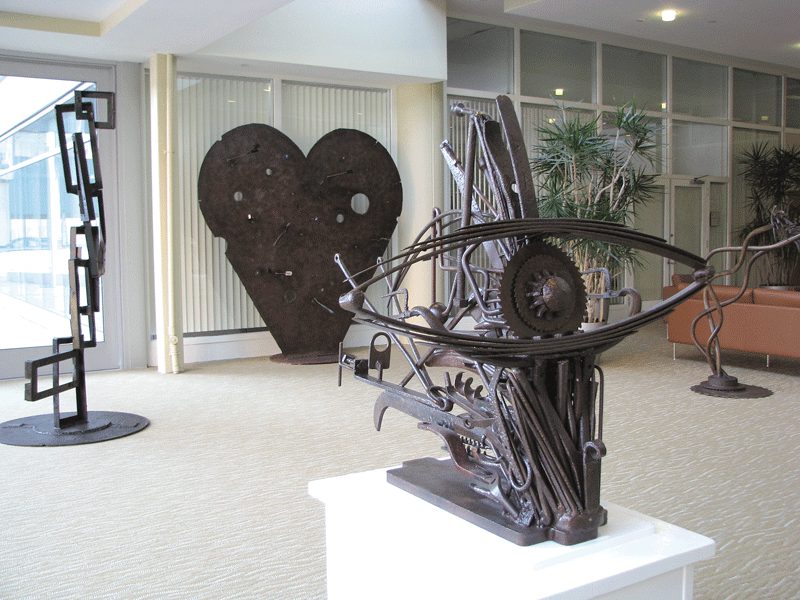

The curious can judge for themselves by visiting the main lobby at 1550 Main St. in downtown Springfield, where about 50 of Kitchen’s pieces of various sizes are on display (and for sale in a partnership with WGBY to help raise money for the public television station) as part of a three-phase initiative that is about much more than art — although that’s a big part of it.

It’s also about Springfield, its history, especially a proud manufacturing heritage, and about celebrating the city’s downtown and ongoing efforts to revitalize it. And it’s about using art to bring people — and attention — to the central business district.

This unofficial mission brings Kitchen to the German word denkmal. He heard it while in Austria in reference to the sculptures he saw on nearly every street corner — “I thought to myself, ‘this is how society should be.’” The literal definition of the word is ‘monument,’ or ‘memorial,’ but Kitchen says he’s heard it broken down to create a different meaning.

He said he’s been told that ‘denk’ means to think, and ‘mal’ means ‘for a minute.’ Add it up, and you get ‘think for a moment,’ which is what he wants people to do with his art — but also with downtown Springfield.

And while thinking, he wants people to appreciate the architecture, the green spaces, and the growing sense of energy he’s sensing during what have become twice-weekly visits to the city from his studios in Chesterfield.

Kitchen’s art will soon be gracing a number of buildings and landmarks in the downtown area (phases two and three), from the fountain in front of 1350 Main St. to some of the open spaces on or near Main Street, to the headquarters of WGBY. In the meantime, he’ll become more of a fixture himself, becoming the most visible personification of an effort to use art as an economic-development strategy.

For this issue, BusinessWest talks with Kitchen about his works — and his work to put art and downtown Springfield in the spotlight.

Portrait of the Artist

As he talked with BusinessWest about his work, Kitchen summoned a phrase he’s used often with the media over the years.

“It’s like doing a jigsaw puzzle without a box … you have to listen to the parts and pieces, and they often come together in ways you wouldn’t necessarily think at the beginning,” he said of his sculptures. “You take this cold, lifeless metal, and you animate it and give it a personality.”

Kitchen’s work falls into the genre known as ‘found art,’ or works created from objects, sometimes modified in one way or another, that are not normally considered art. In his case, what’s found are discarded metal parts, tools, and utensils, usually rusted out, the condition he favors due to the reddish/brown color.

He’s discovered such items at auctions and in basements, attics, barns, junkyards, and other locales. “I’m on a first-name basis with the people who work in recycling facilities,” he explained, adding that he always has a large pile of this inventory at his studio.

The components in his works range from automotive brake cylinders (often used as bases for the sculptures because of their size, shape, and weight) to shovels and rakes of all shapes and dimensions, to something common in his home state of Wisconsin, but not so much here — stanchions used in the process of milking cows. Often, what results is what he called a “where’s Waldo effect,” as people young and old search for and find things they recognize.

When asked when and why he started creating items like “Steel Life,” Kitchen flashed back to a vacation on the Maine coast many years ago, a much-needed break from his pressure-packed job in book publishing.

“I was in the book-production part, and that’s a very stressful job,” he explained. “That’s because everybody would be late — the writer would be late, the artist would be late, but it was my job to get a book out on a certain date; that date would be looming, and you’re trying to get people to focus — that’s where all the stress comes from.”

While at the beach, Kitchen started to take some of the many rocks strewn about at low tide and fashion them into vertical sculptures. The assorted works caught the attention of one passerby, an art teacher from New York State, who, said Kitchen, changed his life by asking the simple question “who’s the artist?”

Fast-forwarding a little, Kitchen said the moment provided an epiphany that compelled him to eventually ditch book publishing for found art, starting out with “something created from an old frying pan that wasn’t very good.”

Over the past 15 years, though, he’s obviously improved, as evidenced by the fact that his works, including the massive, 3,000-pound “Saturn,” have been displayed at venues ranging from Smith College to the Springfield Museums to the lawn of the Hampshire County Courthouse, and also sold at a number of art shows.

It was while displaying at one of these shows, the Paradise City Arts Festival in Northampton, that Kitchen made the acquaintance of Evan Plotkin, president of NAI Plotkin and an ardent supporter of efforts to revitalize downtown Springfield through the power of art, and started discussing possibilities for making the City of Homes, or at least its downtown area, a gallery for his work.

Heavy Metal

There’s an office of the Internal Revenue Service on the ground floor of 1550 Main St., and visitors to that facility comprise a good share of the audience viewing Kitchen’s work to date.

“It’s a tough crowd,” he joked, noting that many visiting the IRS are not in a good mood before, during, or after conducting business.

Still, many are prompting him to make use of that term denkmal. “They’re stopping, looking, and thinking for a moment,” said Kitchen.

And they’re doing so while taking in such works as “The Universe,” the largest of the pieces on display in the building at more than 800 pounds. Explaining the work and its name, Kitchen said the collection of parts, including a 150-year-old, star-shaped seeder, invokes (to him, anyway) thoughts of time, energy, and even the Big Bang Theory — hence the title.

There’s also a vertical, cubist-like piece he calls “Picasso Walking to Work.” Why? “Because when I look at it, that’s what I see — Picasso walking to work in the morning.”

And then, there’s “Salvador Dali’s Toolbox,” an actual metal toolbox filled with real, but very oddly shaped and designed, tools, many a century or more old, by Kitchen’s estimation. Explaining the work and the name is made more difficult, he said, because not many inquirers seem to know much, if anything, about Dali.

As he discussed the toolbox and other works, Kitchen gestured to his pickup truck parked on Main Street. In the back was a six-foot-high prototype of another bird-like sculpture (there are many in the portfolio) that will reach a height of 30 feet and, according to current plans, be erected near the fountain at 1350 Main St.

This is a big part of phase 2 of this endeavor, which involves larger pieces and a broader presence across downtown. Kitchen is currently working with Plotkin, Springfield Business Improvement District Executive Director Don Courtemanche, and others to establish venues for his work. Phase 3, meanwhile, involves the incorporation of some of Springfield’s manufacturing history in his creations.

James Kitchen’s creation called ‘The Universe’ is the largest on display at 1550 Main St. in Springfield.

And while taking in the art, Kitchen and others involved with this initiative hope that people will also take in downtown Springfield, and perhaps see it in a different light — beyond the new art — which Kitchen already does.

“Six months ago, if I had talked about Springfield, I would have given you a completely different story,” he told BusinessWest. “As you watch the news, you get this sense of Northampton as this art town, and Springfield, well, that’s the place somebody got killed — that’s the sense you get. But now that I’ve been down here … what a wonderful city. I don’t think the news really portrays the excitement and the many things that are going on here.”

Meanwhile, he says being in downtown Springfield (as opposed to ultra-rural Chesterfield) is influencing his work.

“I’m building things taller,” he said, noting that he’s being influenced by neighboring office towers. “The bird will be 30 feet tall, and other pieces I’m planning will be pretty big. I’ll be up on a ladder, which is pretty daunting.”

All’s Weld That Ends Weld

Kitchen, who said his favorite piece is “always the last one that I make,” told BusinessWest that the prices on his creations vary, from a few hundred to several thousand dollars. Size has something to do with the figure sought, but bigger factors are the amounts of time and energy spent on a piece.

“And half of my time is spent out finding this stuff,” he continued. “Most of the time you’re getting it from some farmer who lived through the Great Depression and never threw anything away.”

Thus far, the works are doing what Kitchen intended — they’re getting people to stop and think, “which is what an artist does, really.”

Whether his found art can get people to stop, think, and perhaps better-appreciate downtown Springfield remains to be seen, but he certainly has a steely resolve — and in more ways than one.

George O’Brien can be reached at [email protected]