Creating Impact

Anyone who hasn’t been to the Massachusetts Museum of Contemporary Art in the past decade might be surprised at how different it is from its early days. From a near-doubling of art space to a growing array of long-term exhibits to a robust music, theater, and festival business, MASS MoCA has become a true driver of Berkshire County’s creative economy — and that’s by design.

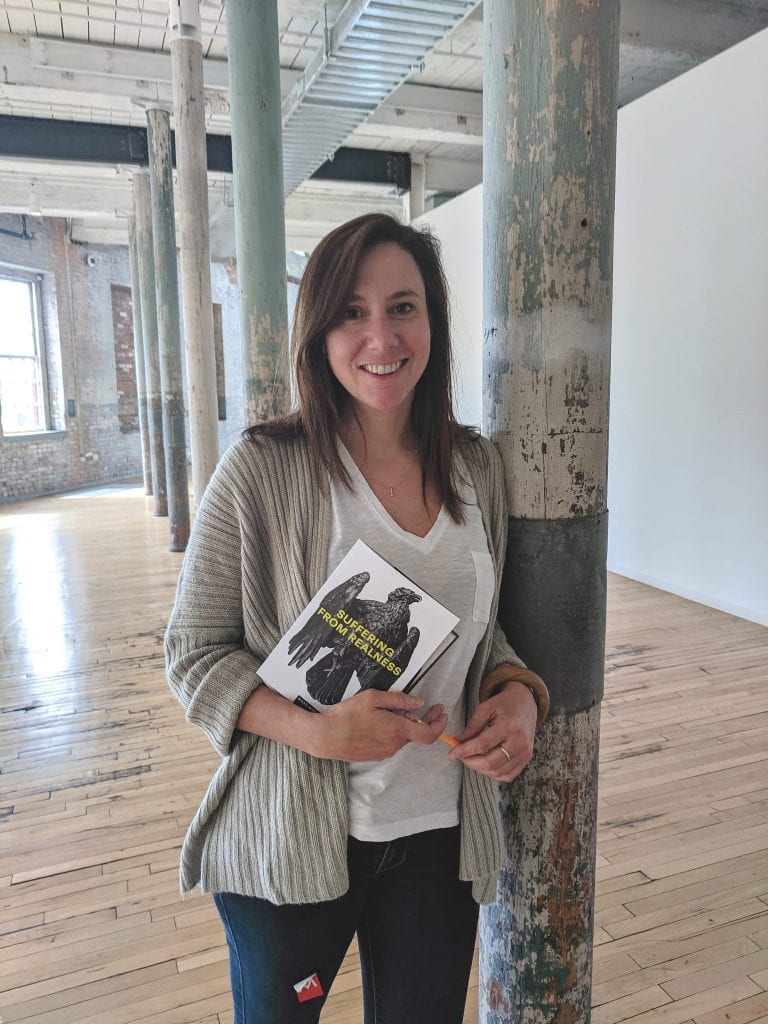

Jodi Joseph understands the challenges of drawing visitors to a museum in — well, it’s not the middle of nowhere, exactly, but it’s also a far cry from Boston or Manhattan.

“We have 13,000 residents in town. We bring over 200,000 people to the galleries every year. That’s a hard thing to do,” said Joseph, director of Communications at the Massachusetts Museum of Contemporary Art, or MASS MoCA, in North Adams.

But it’s an important thing, she added — not just for the museum, but for the entire region’s creative economy.

“People from 75 miles or more from here know this is a place to see art. Within 75 miles, more people know us as a place to see music and performing arts,” she told BusinessWest during a recent visit. “We are finding more ways to draw connections between the performing and visual arts — to let those visual-arts people know we have this dynamic performing-arts program year-round, and get our performing-arts audience into the galleries to see everything here.”

That’s because more time spent here means more money spent in the northwestern corner of the state.

“Overnight visitors spend six times as much money as day visitors,” Joseph went on. “Part of our economic-development agenda is getting people to understand there’s so much to do at MASS MoCA, and we’re just one of several institutions up here. So if you want to come see us and the Clark [in nearby Williamstown], you’re going to have to spend a night, maybe two nights, to get it all in. Every admission here is good for two days. So stay awhile — there’s so much to see.”

Much more, in fact, than when the museum opened 20 years ago, or even 10 years ago, for that matter. Growth has been a constant in MASS MoCA’s second decade, with the addition of a robust performing-arts and festival business and a massive expansion of floor space to accommodate something unheard of in the early years: permanent exhibits.

Much credit for the former goes to the Chicago-based rock band Wilco, which, a decade ago, became enamored of Western Mass. and saw it as a place to establish a residency and work on side projects. They couldn’t make a connection with Tanglewood work, but when they visited MASS MoCA, they knew they had something. In 2010, the museum launched Wilco’s first-ever Solid Sound festival, a celebration of music and art now held every other summer.

“Thus began MASS MoCA’s foray into a pretty serious concert-festival business,” Joseph said. “It opened the idea of MASS MoCA, this campus, being a destination for music. It was such an exceptional marriage — the fanbase their music attracts was our target audience. There are many other bands we could say that about, but certainly Wilco is in the top 10.”

Today, MASS MoCA presents more than 75 performances year-round, including contemporary dance, alternative cabaret, world-music dance parties, indie rock, outdoor silent films with live music, documentaries, avant-garde theater, and an annual bluegrass festival known as Fresh Grass.

But the museum’s calling card is still modern art — in particular, large-scale, immersive ‘installation art’ that would be difficult to house in conventional museums. The unconventional works form an intriguing counterpoint to the century-old, high-ceilinged mill buildings that house them, which have retained their raw, industrial character over the years, with plenty of exposed brick, ductwork, and concrete floors.

Joseph said visitors appreciate the palpable sense of history they offer — even as MASS MoCA hurtles into its third decade of challenging the status quo.

Maker Space

The 16 acres of the MASS MoCA’s campus — 26 buildings occupying nearly one-third of the city’s downtown business district — form an elaborate system of interlocking courtyards and passageways, bridges and viaducts; a floor-to-ceiling window in one building overlooks the confluence of two branches of the Hoosic River.

By the late 1700s and early 1800s, businesses at or near the site included shoe manufacturers, a brickyard, a sawmill, cabinetmakers, hat manufacturers, machine shops for the construction of mill machines, marble works, wagon and sleigh makers, and an ironworks.

“Overnight visitors spend six times as much money as day visitors. Part of our economic-development agenda is getting people to understand there’s so much to do at MASS MoCA, and we’re just one of several institutions up here.”

In 1860, O. Arnold and Co. installed the latest equipment for printing cloth; large government contracts to supply fabric for the Union Army swelled business, and over the next four decades, Arnold Print Works became the largest employer in North Adams. By the end of the 1890s, 25 of the 26 buildings in the present-day MASS MoCA complex had been constructed, and by 1905, Arnold Print Works was one of the leading producers of printed textiles in the world, employing some 3,200 people.

In 1942, after a period of decline for Arnold, Sprague Electric Co. bought the site, converting the textile mill into an electronics plant, where physicists, chemists, electrical engineers, and technicians were called upon by the U.S. government during World War II to design and manufacture crucial components of some of its most advanced high-tech weapons systems, including the atomic bomb. After the war, Sprague’s products were used in the launch systems for Gemini moon missions, and by 1966 Sprague employed 4,137 workers. But, again, sales eventually declined, and in 1985, the company closed its North Adams operations.

“This campus has always made things,” Joseph said. “Now, what we make is art — performing arts as well as visual art.”

Indeed, when North Adams leaders began discussing a new use for the campus, the Williams College Museum of Art was seeking space to exhibit large works of contemporary art that would not fit in conventional museum galleries — and the idea of creating a contemporary arts center in North Adams began to take shape. With funding from both public and private sources, MASS MoCA opened in 1999.

Banners promote current, temporary exhibits, but MASS MoCA has developed an array of long-term exhibits by prominent artists as well.

The ‘maker’ spirit of the complex extends to putting up the installations, many of which are not as simple as hanging a painting. The museum typically doesn’t hide the process, which can take several weeks, but instead embraces it.

“Because of the way our galleries are situated, we can’t help but put ourselves on view when installing an artist,” Joseph explained. “You might walk through and observe someone charging through the gallery with a forklift. This time of year, we’re moving from one gallery to the next, installing new art, and all that activity is usually on view to the public, in addition to everything that’s already installed in the galleries.”

She said the complex, for most of its history, has been home to a constant flow of humanity and industry, and the act of creation is as important — and worthy of viewing — as the static display of art.

“Even if you’re not a contemporary-art person, there’s so much to see in the architecture,” she told BusinessWest. “The buildings themselves are art. The fact that we fill them with art and ideas, and made these buildings accessible to the public, is a joyful experience. My grandparents worked here. My mom worked here. That’s real. I love coming to work every day and being in this site where I know my family history looms large.”

Even the performing-arts elements of the museum embrace the process as much as the outcome. For instance, in 2012, rock icon David Byrne teamed up with director Alex Timbers to create a theatrical piece called Here Lies Love — and, rather than perform it only as a finished product, presented it to audiences as a work in progress.

Similarly, just this year, actor Jon Hamm, director Danielle Agami, and Wilco’s Glenn Kotche led a team that developed a piece called Fishing, also performing it as an evolving work to audiences who were then invited to talk about what worked and what didn’t for them.

“It’s a phenomenal exchange — audiences love it,” Joseph said. “In this culture-drenched region, people get really excited about the creative process. Even if you are not the creator, you get to be involved.”

Permanence in Change

The process of developing and expanding an artistic idea has also taken shape on a macro level over the past decade on the MASS MoCA grounds. In 2008, the museum opened its first long-term exhibition, a three-story space housing about 100 works by famed large-scale wall artist Sol Lewitt — a display the Los Angeles Times once called “America’s Sistine Chapel.”

In 2013, the campus opened a previously unused building for a long-term exhibit by painter and sculptor Anselm Kiefer. And in 2017, the museum activated more buildings, almost doubling the previous gallery space from 135,000 square feet to 250,000, and installing permanent works by neoconceptual artist Jenny Holzer, multi-media artist Laurie Anderson (who makes use of virtual reality in her gallery), and James Turrell, whose interactive works make intriguing use of light and space, just to name a few.

The museum installed this floor-to-ceiling window to give visitors a view of North Adams and, in particular, the point where two branches of the Hoosic River join up.

“Part of the joy of going to a museum is seeing the permanent collection,” Joseph said. “You might return time and again and see new exhibitions, but you can also visit old works in the collection like they are old friends to you. We never had that at MASS MoCA because we only had rotating exhibitions.

“But in 2008,” she went on, “people started to think about MASS MoCA not just as a pilgrimage site for Sol Lewitt fans, but also as a place where visitors could return and find something new at the galleries, but also have this body of work, this artist’s life work, where they were suddenly becoming experts. MASS MoCA members probably know more about Sol Lewitt than many Sol Lewitt scholars.”

The museum has expanded its community connections as well, such as an educational program that brings in 2,500 students from local public schools several times a year. Partner schools develop a curriculum of class projects based on what the students see at MASS MoCA. An invitational program for promising teenagers actually displays their artwork on the museum walls and provides grants to their teachers to stock their classrooms. One area teacher used the grant to purchase a kiln so students can create pottery.

“For these kids, she added, “seeing their art on the walls beside Sol Lewitt kind of raises the stakes for them.”

Another program, called the Studios at MASS MoCA, has hosted more than 500 artists and writers for residencies up to 10 weeks. Hosted by the museum’s Assets for Artists program, selected artists receive private studio space on campus, in addition to housing, free access to the museum’s galleries throughout the residency, optional financial and business coaching from Assets for Artists staff, and a daily group meal.

As part of its examination of the regional creative economy, the Berkshire Blueprint 2.0, a county-wide economic-development plan, recommended expanding the Studios program throughout Berkshire County, she noted. “I’m not sure how that would work, but it’s a great concept.”

And an exciting one, as MASS MoCA has long been a draw to this small city near the New York and Vermont lines — and from that destination status comes myriad ripple effects.

“We were founded with a two-headed mission,” Joseph said. “One was to present the best art of our time, and the second was to be an economic catalyst.”

It does that by leveraging all this activity — not just the performance and display of art, but its very creation — to develop new markets for artists, spur job creation, strengthen community identity, and even boost property values, all of which Joseph has witnessed and hopes to see continue.

“We’re in one of the most robust real-estate moments in North Adams in my adult life,” she said. “We’re happy to contribute to it — even if it’s one by one.”

Joseph Bednar can be reached at [email protected]