Unequal Rights?

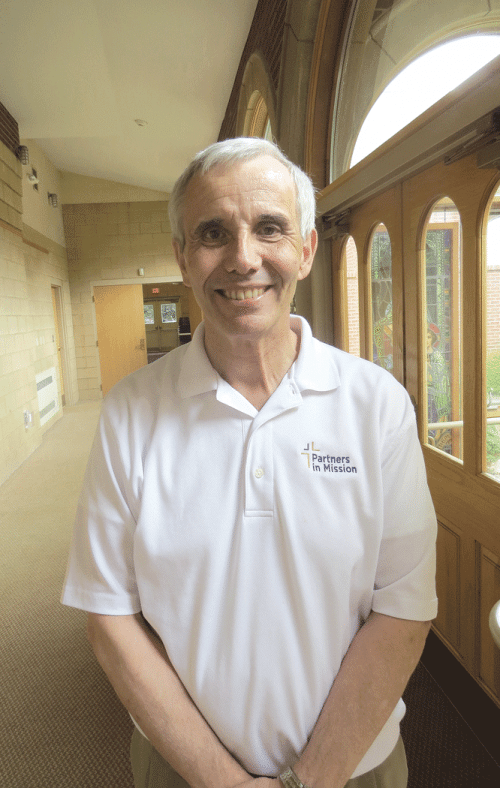

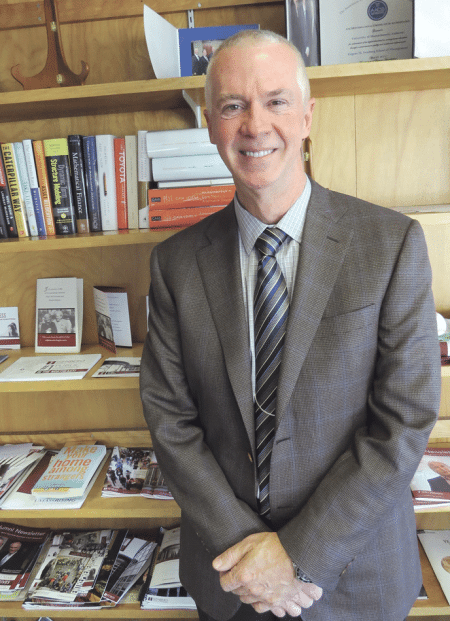

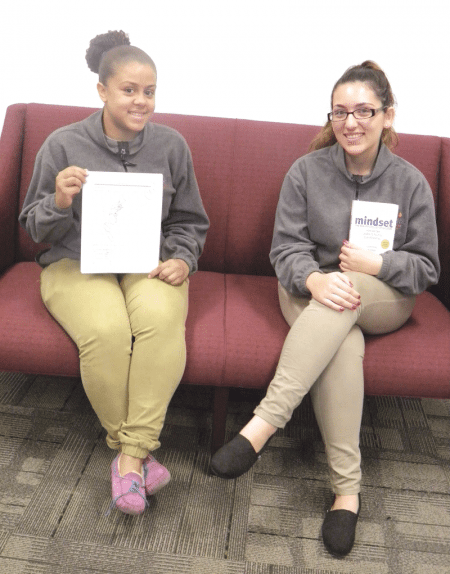

Bill Spirer says ballot Question 2 is about expanding charter schools in underperforming districts where students historically have had few options.

Todd Gazda stopped along the Riverwalk in Ludlow to admire the view a week ago and began talking with a senior citizen who was relaxing at the site.

“As soon as he found out who I was, he asked me what I thought of Question 2,” said the Superintendent of Ludlow Public Schools, adding that the gentleman was extremely interested in the issue.

Indeed, the question that will appear on the November ballot is significant because it is the first time in state history the public will have the opportunity to voice their opinion about school choice.

If passed, Question 2 would give the state Board of Elementary and Secondary Education the authority to approve 12 new charter schools or expand existing charter schools as a result of increased enrollment every year beginning Jan. 1, 2017. Priority would be given to applicants in public-school districts that score in the bottom 25% on standardized tests two years before their application. In addition, the Board of Elementary and Secondary Education would establish standards by which annual performance reviews would be judged.

The question has generated strong feelings, heated arguments, and major fund-raising campaigns: when BusinessWest went to press, proponents had raised $18 million and opponents $12 million, most of which will be spent on TV ads.

The debate began in earnest last year after Gov. Charlie Baker, who is a strong a proponent of charter schools, introduced a bill to increase their number in the Commonwealth. The Senate revamped the proposal before passing it, but it was rejected by the House, which didn’t support the changes that had been made.

Lawmakers continue to be heavily divided on the issue, but after the House rejected the bill, the Mass. Charter School Assoc., Great Schools of MA, and Democrats for Education Reform led an effort to get the question on the ballot to increase options for the 32,000 students on charter-school waiting lists.

Both sides have powerful arguments. Opponents say charter schools don’t serve the same number of English-language learners (ELL) and students with profound special needs who require costly services; the admissions process is unfair to students whose parents are not interested in their education or don’t have the skills needed to seek information or enrollment in alternate schools; the state has failed to provide the level of reimbursement promised to public schools when a student leaves their district for a charter school; building and staffing costs don’t decrease when students leave; and charter schools are not subject to the same standards as district public schools, which makes it easy for them to eliminate students with behavior problems.

Todd Gazda says the amount of money Ludlow loses every year to charter schools is more than the amount allotted to run an elementary school.

Proponents argue that they admit students by lottery and serve a diverse population; their behavioral standards are strict but fair; their academic results are higher than urban and suburban schools; they offer students in low-performing districts a chance to get a high-quality education; the funding formula does not discriminate because money allocated to each student in a district simply follows them; and they are actually public schools that are open to all students and don’t charge tuition.

But both charter- and public-school directors and superintendents agree that money is an important issue because schools across the state are grossly underfunded.

“My fear is that the debate over charter schools will divert attention from the bedrock issue of school funding in general,” said Northampton School Superintendent John Provost, referring to a study conducted last year by the Foundation Budget Review Commission, which looked at the formula used to fund public schools and found a $1 billion deficit.

The Mass. Assoc. of School Superintendents thinks the amount is closer to $2 billion, and Provost argues that the ballot question is secondary to financial problems facing all public schools, which include charters.

“I feel it’s the wrong policy to be voting on at this time,” said Provost. “Charter schools were created when the education budget was growing, but in many communities funding has been stagnant since 2008, and it’s a matter of diverting money from a pie that is not growing.”

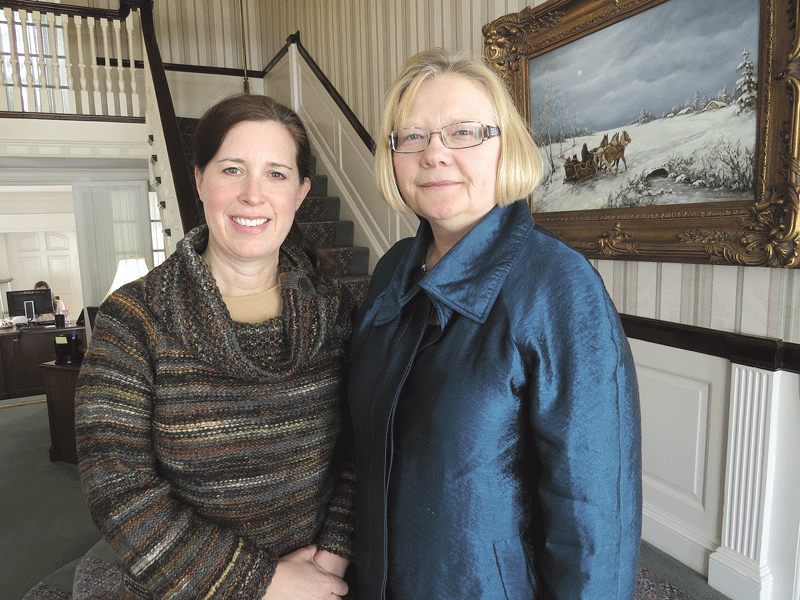

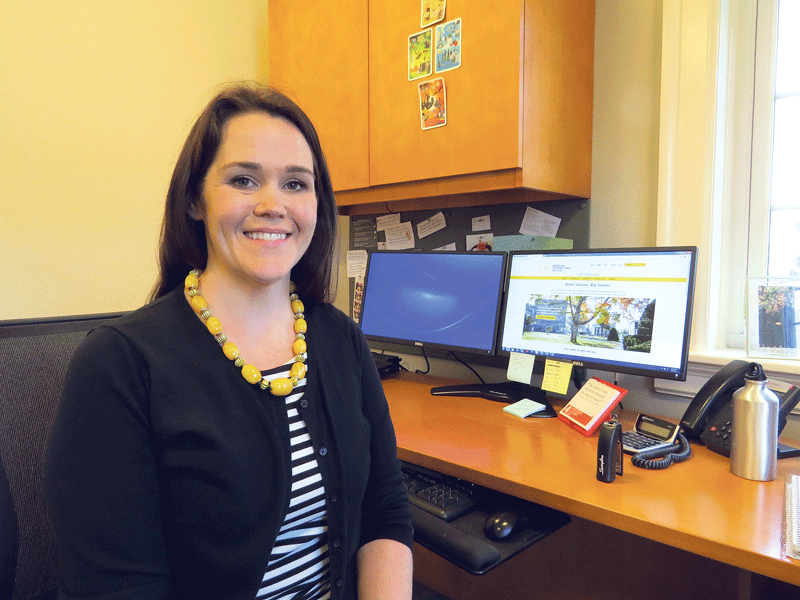

Karen Reuter says charter schools were founded to model innovation and specialization, and were not meant to replace public schools.

Sabis International Charter School Director Karen Reuter agrees that state funding for education is inadequate. “If we could raise the bar for every student, maybe we wouldn’t have to have such an oppositional agenda,” she noted.

But she says the issue comes down to access to quality education, which makes the ballot question important.

For this edition and its focus on education, BusinessWest looks at arguments on both sides of the question and what will be at stake when voters go to the polls.

Shortchanging Students

Barbara Mandeloni, president of the 110,000-member Mass. Teachers Assoc., says $450 million diverted from district public schools to charter schools has had considerable consequences, and some schools have had to cut support services to children with special needs, while others have cut teachers or language classes and other extra curricular programs.

“Public schools represent the best of who we are and contribute to the common good; they are not about individualism, but about a shared sense of purpose and something bigger than ourselves,” she said, adding that the New England NAACP is a leader in its coalition and Black Lives Matter has called for a three-year moratorium on charter schools because, critics say, they are creating a two-tiered system that is resegregating schools.

“We need to defeat this bill, then have a conversation about funding so we can give every child the opportunity to have a broad and rich curriculum and access to resources,” she said, adding that many charter schools have discipline standards that force students with behavioral issues out.

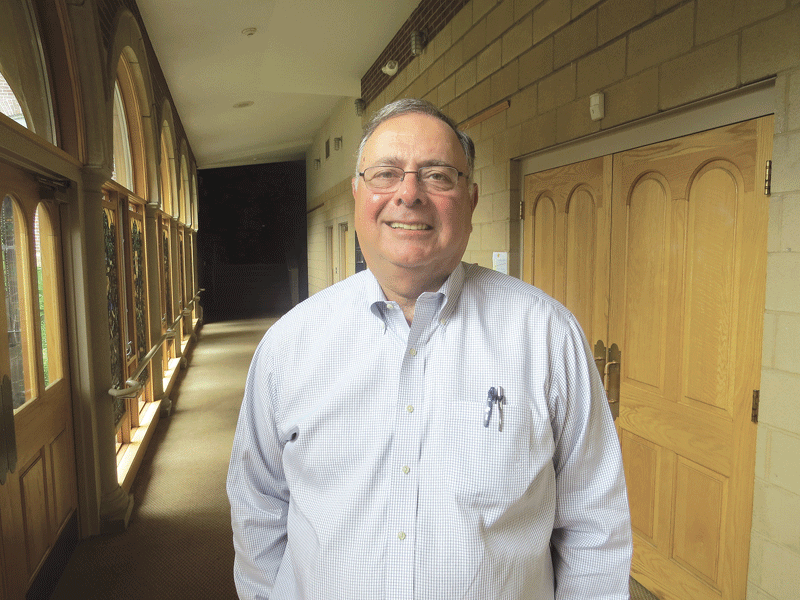

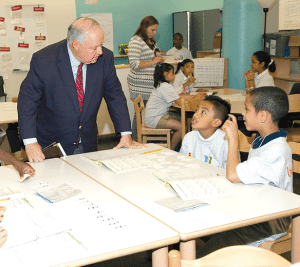

Daniel Warwick says charter schools have a large, negative impact on Springfield’s public schools.

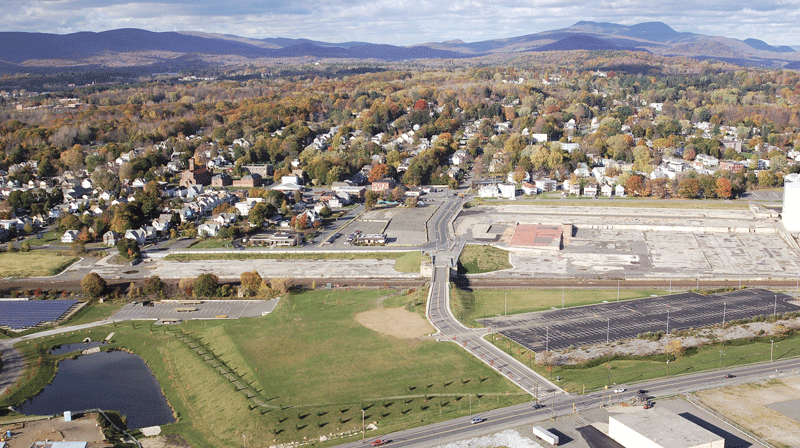

Springfield School Superintendent Daniel Warwick says adequate funding for urban schools has always been a problem, and they barely make the minimum net school spending needed to educate each child. And the impact of charter schools on the Springfield district has been tremendous; they lose $41 million each year to charters and are reimbursed only $6 million, but still have to educate an extremely diverse population that includes many refugees who have undergone tremendous trauma in refugee camps, as well as a large number of students with profound special needs, including some who enter the ninth grade after never spending a day in a school.

“We have the most difficult students to educate. There are a lot of English-language learners and students with special educational needs who are the most difficult and costly to educate in terms of achievement results,” he said, noting that, although charter schools say they do outreach, the percentage of high-need special-education students they serve doesn’t rival that of the sending district, which is a nuance in achievement levels that hasn’t been addressed.

He thinks equal access to education would mean that charter schools hold lotteries that include all students in their district, not just those whose parents are motivated to fill out application forms, which is often prohibitive due to language and socioeconomic barriers.

“If we are going to continue the charter-school movement, there are issues that need to be addressed, and making sure their populations match their sending communities in every way is one of them,” he said, adding that, if charter schools are not educating the most needy students, their achievement results need to be called into question.

“It’s a lightning-rod issue on either side, but from the perspective of public-school funding and student-assignment structure, it is particularly troubling because once you go to a lottery system you are dealing with a different population,” Warwick continued, noting that the demographics in the city’s magnet schools also differ, especially in terms of parent involvement.

Springfield schools had to cut $13 million from a budget this year that was already underfunded by $10 million, and the loss was increased by a $3 million shortfall from the state’s failure to reimburse them appropriately for students lost to charter schools. Another $5 million was lost to school choice, which doesn’t account for the fact that Springfield has to provide transportation for these students.

“We have had to cut direct services to kids and 56 positions from our central office,” he said, “and class sizes will continue to grow if the funding stream isn’t changed.

“If we were funded according to the findings of the Foundation Review Commission’s recommendations, we would have $25 million more this year to adequately address the students we serve,” he went on, adding that this is a social-justice issue.

Gazda agrees, and says proponents argue that Question 2 comes down to school choice.

“But when you dig deeper, the facts below the surface reveal a different picture; we are one of relatively few districts who lose very few students to charter schools, but geography does make a difference,” he explained. “Charter schools are being held up as a better alternative, and that narrative is just not true; their students don’t perform remarkably better than most public-school students.”

The state is supposed to reimburse district schools 100% of the money they lose the first year a student switches to a charter school, and 25% for each of the following four years. But not only has it cut school funding in general, it has not come close to meeting those numbers.

Ludlow lost 19 students to charter schools in FY ’16, which cost $434,878, but was reimbursed only $122,467.

“It had a marked impact on us and the things we could do. In a school system the size of Ludlow, $300,000 can go a long way,” Gazda said, adding that there is no way for local school boards to judge whether charter schools are using funds efficiently.

In addition, charter schools were originally created to have the flexibility to be innovative in creative ways and share their best practices with local school districts, which Gazda says has not happened.

“The way the system is set up is competitive and almost adversarial, because of the flow of resources away from district public schools. It has the effect of creating a tiered education system, particularly in urban areas,” he continued, noting that parents in urban areas often cannot afford to move to towns with better school systems; Ludlow has a wait list of 350 students for school choice, and the vast majority are from Springfield.

He said a single mother who wants the best for her child often views charter schools as a place where the child can be saved. “But my answer is to fully support public schools so we can change the environment in all schools.”

Northampton recently commissioned a survey of charter-school parents to learn why they were opting out of their neighborhood schools.

“It showed the charter-school population is very unique in terms of demographics; 100% of the parents said they had a college degree, the majority had graduate degrees, and their household incomes were far above the incomes of local families,” Provost said.

Last year, Northampton Public Schools received about $644,000 less from the state than in 2010. The city has 200 students in charter schools, which equates to $2 million in lost revenue each year, and although none of their elementary schools is that small, $2 million is far more than the amount appropriated to each school.

“The main impact is the loss of programs we can provide,” Provost said, adding that more than 20% of their students have disabilities.

Different Agendas

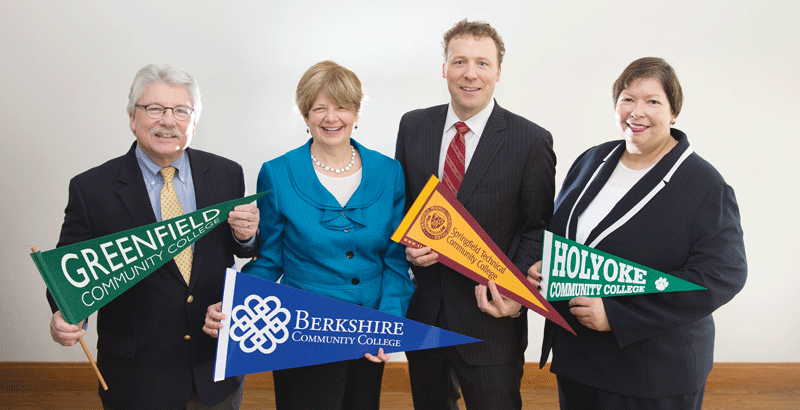

Dominic Slowey says the governor modeled his original bill on a draft ballot question put together by charter advocates.

“The majority of charter schools are in urban districts that are underperforming, and the ballot question is their last resort,” said the spokesperson for the MA Charter School Assoc. “Springfield only has room for one more charter school with 400 to 500 seats, and many cities, including Holyoke, Lawrence, Lowell, and Fall River, have reached their cap. In many cities, parents don’t have enough high-quality public-school options, but charter schools have worked to fill that gap and put them on an even keel with communities like Longmeadow, Wellesley, and Amherst.”

He added that charter schools have reached out to low-income African-American and Latino families, and by every independent measure, the schools have outperformed not only urban schools, but suburban schools.

There are 72 charter schools operating in the state, and the approval process is difficult, so only three to four schools a year make the grade.

Proponents also explain that charter schools are heavily regulated by the state; their finances and academic progress are monitored annually and they must continue to set new goals. In addition, they are subject to a five-year review, and if they fail to live up to their charter, they can be placed on probation or closed, which has happened to two Springfield charter schools.

Sabis International Charter School in Springfield serves children in kindergarten through 12th grade who reside in the city. It has won national awards since it was founded in 1995 and has a waiting list of 2,900 that is rigorously combed every year to ensure it is accurate, which has been done in response to arguments that the waiting lists for charter schools are outdated and inaccurate.

As at other charter schools, admission at Sabis is by lottery for the 100 kindergarten seats each year, and since its retention rate is 90%, there are few backfills.

Sabis is housed in a beautiful facility backed by Sabis Educational Systems, but Reuter says some charter schools are financially challenged and have to engage in considerable fund-raising.

“But money doesn’t guarantee positive outcomes,” she said, noting that she has served in a variety of educational settings, including a stint as a union teacher in New York City. “Education is a changing landscape with new standards and assessments, and this bill is really about whether students can access quality education. But it’s a shame that we have gotten to a place where people have to vote, because we all want the same thing: to provide the best education possible for every student.”

Historically, the school’s population has been equally divided between Caucasian, Hispanic, and African-American students, but recently the number of Hispanic students has increased, and the Asian population is growing. Its ELL population is very small, and only 14% to 16% of those students have special-education needs, but Reuter said they are seeing an increase of students with profound special needs and had to create a separate classroom setting for them last year.

“We don’t serve the same range of special-education students as public schools, but charter schools were not meant to replace public schools,” she told BusinessWest. “They were meant to model innovation and specialization.”

Its sister school in Holyoke serves children in kindergarten through grade 8, and although parents would like to see it expand to the high-school level, the city has reached its cap.

However, Reuter says graduates outperform their peers in Holyoke High School, and it’s unfair that parents and students can’t continue their education at the school of their choice.

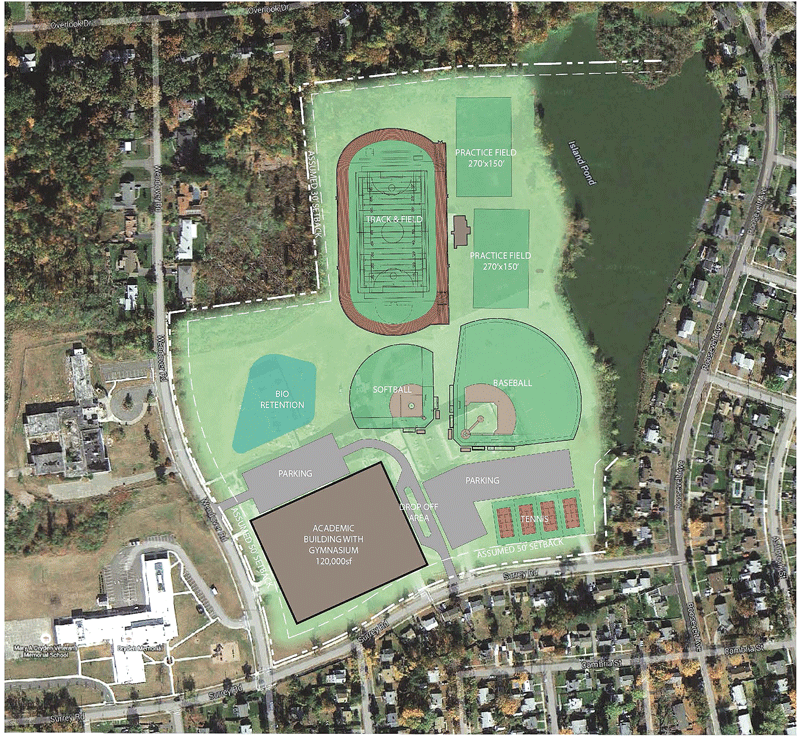

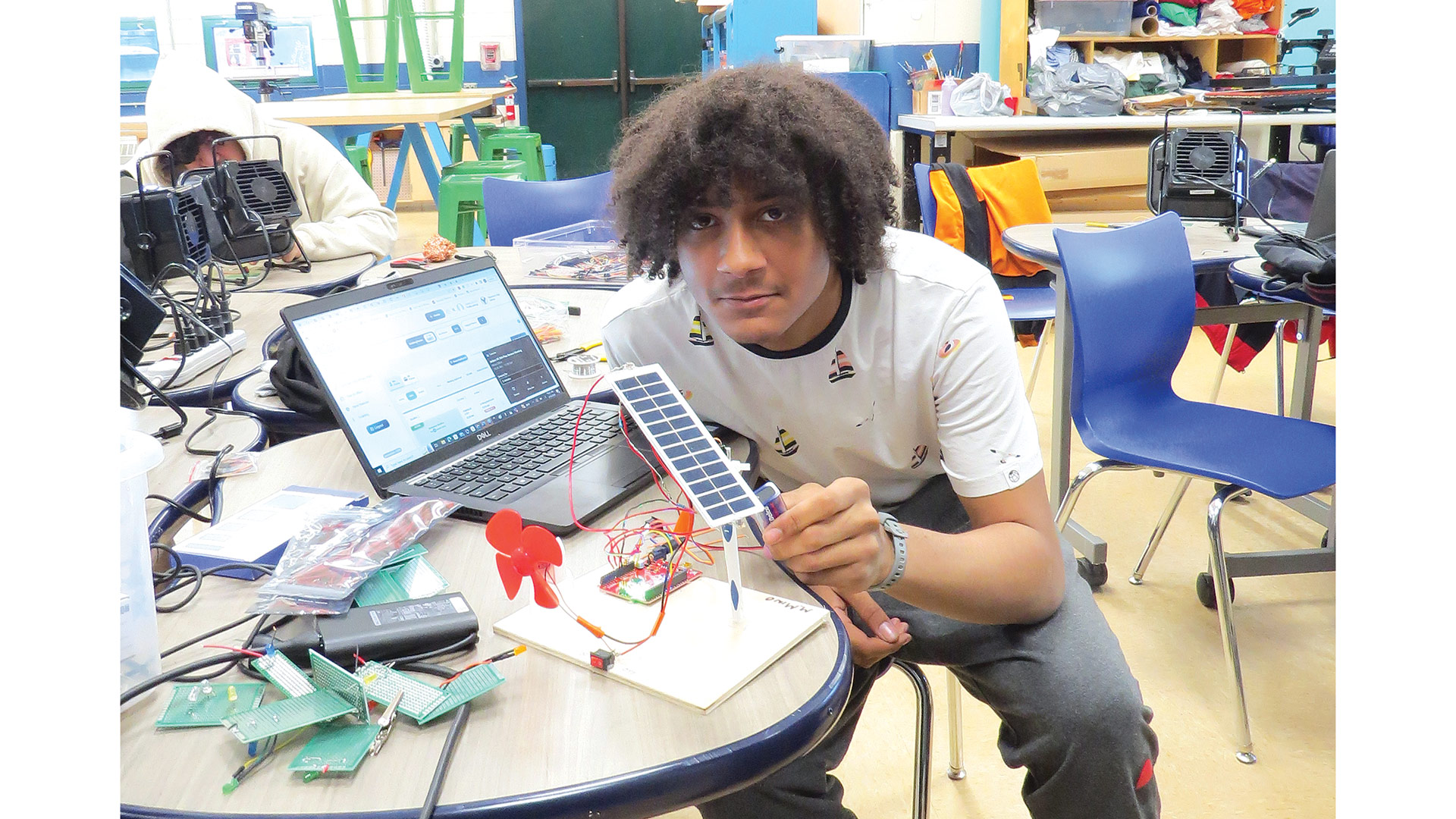

Springfield Prep Charter School opened in Springfield last year with a kindergarten and first grade. A second grade was added this year, and founder Bill Spirer’s hope is to expand to grade 8 by the 2022-23 school year.

There are two full-time teachers in every classroom, and the school has an extended day that runs from 7:50 a.m. to 4 p.m. and a slightly extended school year. All students come from Springfield, and outreach efforts are done in English and Spanish at Head Start programs by volunteers, who also knocked on doors in the city’s South End last January distributing flyers about the school, which has a one-page application.

“Massachusetts has one of the strongest records of charter-school performance in the county, and the data in this state is really clear; charter schools are very effective, especially in urban areas where there haven’t been many good options for parents,” Spirer said, adding that his facility’s demographics mirror those in Springfield Public Schools and nine out of 10 students are from economically disadvantaged families

Richard Alcorn, executive director of Pioneer Valley Chinese Immersion School in Hadley, says it provides a unique curriculum and wants to expand to a fully articulated K-12 program.

“The charter schools in Hampshire and Franklin counties really serve as alternative schools,” he noted, adding that his school serves students from 30 districts and 17.5% are from low-income families, which is lower than urban centers, but higher than the school’s host community, where 13.2% of students fall into that category.

But he agrees that funding is inadequate for all schools. “People need to step back and look at what is going on in public education. The impact of charter schools is very small and has nothing to do with the real problem of funding and what is going in terms of demographics,” he told BusinessWest.

Far-reaching Implications

Charter schools all have different missions and leadership, and serve different communities, so Spirer says they can’t be classified with the same adjectives.

“It’s a very complicated issue that has different implications for districts of different sizes. But the ballot question is still about the most underperforming districts,” he explained.

Gazda says perception is reality, and right now the narrative coming from Boston and Washington is that public schools are failing, which is not true.

“However, we need new solutions rather than garnering old ones that don’t work,” he said.

These wide-ranging observations and opinions only scratch the surface when it comes to the high levels of debate and controversy that define ballot question 2. About the only certainty is that the matter is now in the hands of voters.