Dollars and Sense

By Mark Morris

From left: Square One’s Dawn DiStefano, Melissa Blissett, and Kristine Allard; and FP Investment Group’s Flavia McCaughey, Flavia Cote, and Peter Cote.

Given the scope of Square One’s work for children and families, it’s not unusual for the organization to receive contributions to support its efforts.

But recently, FR Investment Group offered a donation that goes far beyond writing a check.

“Instead of making a monetary donation, we’ve chosen to do something harder,” said Peter Cote, president of FP Investment Group. “We’re giving our time and services to help Square One clients and staff improve their financial literacy.”

Dawn DiStefano, Square One’s executive director, had seen similar attempts at financial education fizzle out, despite good intentions. This latest proposal was different.

“The FR group wanted to understand who we are and what we want for our clients and staff,” she said. “They were curious, inquisitive, and showed us they valued our expertise as well.”

The Empower Financial Literacy program is now a monthly offering at Square One. Flavia Cote, executive vice president of FR Investment and Peter’s wife, runs the session each month with FR staff, including her daughter, Flavia McCaughey, a vice president with FR.

McCaughey presented the idea to her parents that working with families at the lowest income levels to help them understand the basics of finance could have a huge impact on those families — and also on the community at large. The Cotes supported the idea but also offered some sage advice.

“My parents told me to be prepared that maybe only one person would show up to the meeting,” McCaughey said. “I discussed that possibility with the team, and we decided if the program makes a difference in even one person’s life, it’s worth it.”

Instead, 14 people have signed up for the program, with eight or nine regularly attending the monthly sessions.

“Given that we’re still dealing with COVID and that everyone has busy lives, I’m excited about 14 sign-ups,” DiStefano said. “The program will be here when they’re ready. It’s not a one-and-done.”

“Instead of making a monetary donation, we’ve chosen to do something harder.”

Far from it. Peter has committed his firm to running the financial-literacy program for the next 30 to 50 years.

“That’s how long it’s going to take to make real change in the financial well-being of our community,” he said. “You have to be on the ground and commit to the long term.”

Changing the Narrative

This kind of commitment is necessary to break what DiStefano called a self-fulfilling prophecy of bad outcomes.

“Those who grew up in a family where they worried about how they were going to eat and get to school often end up creating that same unstable environment for themselves when they are adults,” she said. “They’re not surprised when they lose an apartment or don’t care about their credit score because they feel they couldn’t buy a car anyway.”

Just like savings, tough situations also have a way of compounding and growing. DiStefano gave an example of someone who lost a job, and in order to receive housing assistance, they had to be in arrears on their rent, which would then negatively affect their credit score. “This is what people are dealing with,” she said.

Melissa Blissett, vice president of Family Support Services at Square One, asks people what’s going on that prohibits them from living a better life and uses a tool called the family-goal plan to help them.

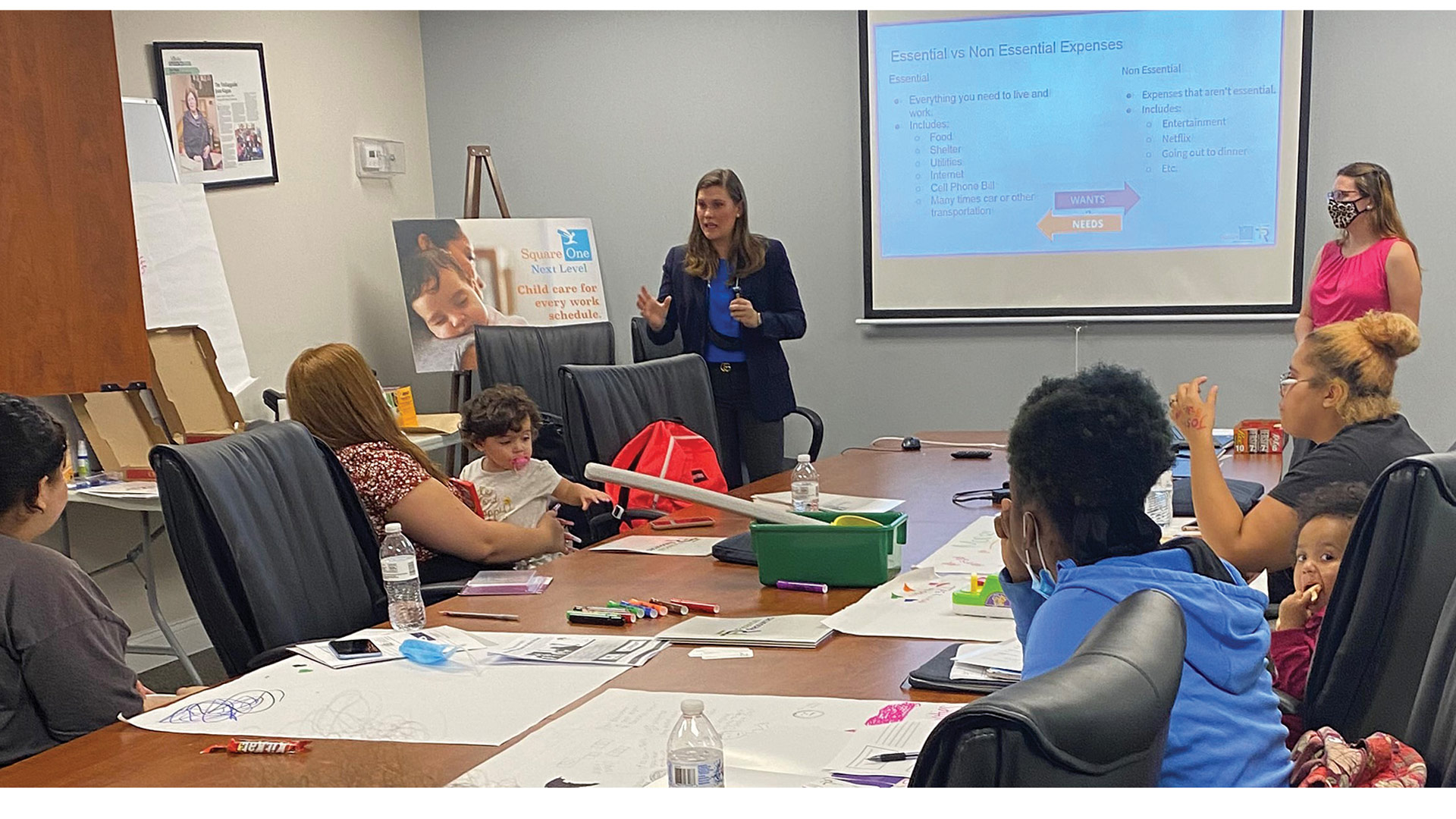

Flavia McCaughey leads a financial-literacy session at Square One.

“The FR folks speak the same language we use with our families, and we both use the SMART goal approach,” Blissett said. SMART, a popular goal-setting technique, is an acronym for specific, measurable, achievable, relevant, and timely.

Flavia Cote said her team encourages people to set a goal such as buying a reliable car, and the FR staff breaks it down to the actions needed to eventually reach the goal.

“We encourage people to try to save at least $10 a month,” she said. “Even if they can’t save $10 next month, they have started to think about saving.”

To prevent being overwhelmed by a large goal, Peter suggests taking it one step at a time. “I don’t want people to think about years from now — just think about the next 24 hours. When you bring it down to 24 hours, you help people see an attainable goal.”

In their monthly sessions, the FR staff help people with figuring the numbers and, more importantly, understanding the emotions that come with handling finances.

“If someone can’t save for one month, we encourage them to set the goal for next month,” Flavia said. “We want to bring hope and make finance simple enough for people to achieve some sort of financial independence.”

Like dedicated saving, positive actions can also have a compounding effect. Recently, a class-action case involving overdraft fees at a regional bank reached a settlement for several million dollars. Once all the claimants received their share, $23,000 remained. This final amount is usually provided to a nonprofit program in alignment with the core theme of the case and is known as a ‘cy pres,’ from a French phrase meaning ‘as near as possible.’

The plaintiff’s counsel, Angela Edwards, learned about the Square One program from Flavia Cote and thought it sounded perfect. “I recommended the cy pres for Square One, the defense counsel agreed, and the judge approved it.”

Making Progress

Peter Cote sees his main job not as a financial person, but as a champion for others. “We’re dealing with people who have a variety of financial challenges, and we are their champions to let them know it will be OK.”

When people attend the sessions at Square One, Flavia said, they show they are ready to make progress with their lives. “We try to help people understand their situation is not permanent and there is a way to change it.”

While a term like financial literacy might sound academic, Peter offered a few different terms that might better describe the course.

“You could call it financial well-being, or Life 101,” he said. “Maybe Figuring It Out 101.”