A New Spin

Westmass Unveils Ambitious Plans for a Ludlow Mill Complex

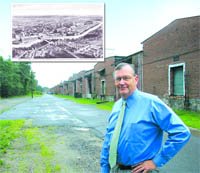

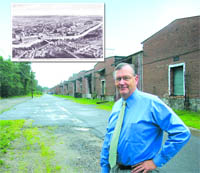

Left, an undated lithograph shows the Ludlow Manufacturing Associates complex nearly a century ago. Below, Kenneth Delude stands near some of the dozens of small stockhouses at the mill complex, which comprise one of many challenges to re-use of the site.

Westmass Area Development Corp. is finalizing acquisition of the sprawling Ludlow Manufacturing Associates complex, which was once the largest jute-making facility in the world. Westmass administrators say the ambitious initiative, which blends elements of greenfield and brownfield development, could, over the next 15 to 20 years, attract perhaps $300 million in private-sector investments and create more than 2,000 jobs.

Its a powerful image a lithograph (date unknown) th.at depicts the sprawling Ludlow Manufacturing Associates complex that gave the community its identity both literally and figuratively.

Indeed, Ludlow has been known throughout most of its 234-year existence as a mill town, and it was known as Jute City thats the product (twine) that was made at the complex. Meanwhile, the clock tower on the northwest corner of what was known years ago as Mill No. 8 has become perhaps the towns most identifiable landmark. It appears on the town seal, the masthead of the local weekly newspaper, the Register, Ludlow High School class rings, and many other places.

The mill complex along the banks of the Chicopee River, including several buildings that are no longer standing, certainly dominates the lithograph, first published in a 1928 book on the making of jute, but thats not the only thing that catches Kenneth Deludes eye.

Look at all the housing, on both sides of the river, that was built by the mill and because of the mill, said Delude, president of Westmass Area Development Corp., who also referenced streets, parks, and the town library as current fixtures that came about as a direct result of the mill complex and its ownership.

At one time, there were about 8,000 people living in Ludlow and 4,000 people working at the mill complex, he said as he moved his hands in a circular motion across the image. When I look at this picture, I think of the enormous regional impact that this complex had the jobs it created were part of the economic fabric of the community. And thats what we hope to do again.

Indeed, Delude sees history repeating itself, albeit on a certainly smaller scale, if an ambitious Westmass project currently in the formative stage unfolds as he expects that it will. The agency, part of the Economic Development Council of Western Mass., is in the process of acquiring what remains of the mill complex some 1.6 million square feet of floor space on a 170-acre parcel, nearly half of it undeveloped and create a mixed-use complex on the site. Preliminary estimates (and they are very preliminary) indicate that such reuse and new development could create perhaps 2,000 or more new jobs, generate millions of dollars in tax revenue, and spur additional economic development much of it in the form of businesses that would support those 2,000 workers.

The business plan for the project, known for the moment as at Rivers Edge (more on that later), is still very much a work in progress, said Delude, who used an enlarged version of the lithograph and some aerial photographs of the site to show what could happen there.

Gesturing toward what is now known as the clock tower building, he said its ground floor could house a bank, a restaurant or two, and other enterprises that would support workers in the redeveloped complex, while its upper floors could house fledgling businesses. Tapping a large, five-story mill building now largely vacant, he said it could be retrofitted into elderly or market-rate housing.

Meanwhile, a currently undeveloped section of the complex could be put toward development of smaller buildings (10,000 square feet to 50,000 square feet) for growing businesses, he continued, while the 79 acres of undeveloped, wooded land could become an industrial park. Several dozen small stockhouses, used to store raw materials for jute making, could be put to imaginative uses, perhaps as incubator spaces, said Delude, adding that many will likely be razed.

All these coulds will be more thoroughly explored over the next 18 months or so, said Delude, adding that the hope is to retain as many of the current buildings as possible to preserve a sense of character and history, while also creating a business park that will help retain existing companies and attract new ones.

The Ludlow project, as envisioned, would be the most ambitious project to date for Westmass, which has developed industrial parks in Agawam, Westfield, Hadley, and East Longmeadow (in that order) and its first true brownfield project meaning development of former industrial space that has environmental issues to be addressed.

Such brownfield development was deemed a priority by the Westmass board of directors, said Stephen Roberts, thats bodys president, both out of necessity and a sense of civic responsibility.

Elaborating, he said the region has many potential brownfield development sites most of them former mills that produced everything from paper to tires and Westmass has committed itself to blending that type of development with the more-traditional greenfield variety that has defined the agencys past and present. Meanwhile, there are simply fewer of those greenfields to be developed, making projects like the one in Ludlow more of a necessity than an option.

In this issue, BusinessWest takes an indepth look at the Ludlow project, as currently conceived, and how this elaborate plan might come together.

Name of the Game Project India.

That was the first, and quite unofficial, name given to the Ludlow project, said Delude, noting that, like most large-scale commercial real estate initiatives these days, this one involved a high level of discretion and thus needed a code name.

This one was chosen because the raw materials that went into making jute came from India, he explained, adding quickly that, now that word is out, Project India is more or less obsolete, and those within Westmass have moved on, sort of. The organization wants to use at Rivers Edge somehow in the name, but hasnt determined yet what to put before those words hence the three dots that currently precede them in large part because the vision of the final product is still being shaped.

That Project India code name was in use for more than a year, or since the start of talks between Westmass and the current owner of the mill complex, Ludlow Industrial Realties Inc. negotiations that were brokered by Doug Macmillan, second-generation owner and president of Springfield-based Macmillan & Son Inc., which has been handling some leasing and other real estate-related matters at the mill complex since it was purchased by Arthur Fastenberg in the late 60s.

Fastenberg eventually acquired several other commercial properties in the region, including the former Westinghouse plant on Page Boulevard in Springfield, which is slated for conversion into a retail complex, said Macmillan. In Ludlow, Fastenberg arranged a sale-leaseback of the property with Ludlow Manufacturing Associates, thus ensuring a prominent, long-term anchor, and many other tenants, large and small, were added over the years.

When I first saw that site back in the 80s, it was really humming, said Macmillan, adding that, until perhaps a decade or so ago, the mill complex was 80% occupied, or more. Over the past several years, that percentage has fallen, reflecting a decline in manufacturing across the region, and the continual downsizing of Ludlow Manufacturing, later to be known as Ludlow Textiles, which moved out completely about 18 months ago.

At or around that time, at the behest of several of Fastenbergs descendents, who now control Ludlow Industrial Industrial Realties Inc., Macmillan approached Westmass about potential interest in the complex.

Initial discussions centered around the undeveloped, wooded portion of the property, said Macmillan, but ownership wanted to sell the entire complex, and quickly convinced Westmass to take that course. More formal discussions took place in New York earlier this year, and, over the course of the past several months, a purchase-and-sale agreement was reached, with the price still undisclosed.

Thus, the Ludlow project becomes what Delude believes is the largest mill-reuse development initiative in New England, and one that will be somewhat unique in that it will focus more on commercial and industrial development than residential, although there will likely be housing components.

This uniqueness makes it hard to find models to follow, said Delude, but there are some.

One is the former Digital complex in Maynard, Mass., which is similar to the Ludlow site, right down to the clock tower, which gives it its name Clock Tower Place. Located along the Assabet River, the 1.1 million-square-foot complex was originally home to the Assabet Manufacturing Co., which made carpets and yarn, and later to DEC, which started as one of many smaller tenants to inhabit the mill in the 1950s, and later occupied the entire complex as Ken Olsens enterprise became one of the leading makers of minicomputers.

But Olsens failure to grasp the concept of the personal computer led to DECs demise, and by the late 90s, the mill complex was almost entirely vacant. It has been rejuvenated with new ownership, and is now home to Monster, the Yacobian Group, and many other tenants.

Another potential model is the Bates Mill Complex in Lewiston, Maine, a 1.2 million-square-foot series of mills that once produced uniforms for the Union army during the Civil War, and is now home to a number of diverse businesses. The list includes the loan-processing operations center for Peoples Heritage Corp., but also dozens of start-up businesses and support services.

Knots Landing

Delude, who plans to visit still another potential model in Rhode Island later this month, said Westmass hopes to take lessons and inspiration from these projects as it goes about writing the next chapter in the history of the Ludlow mills.

If we dont have to reinvent the wheel, then we wont, he said. Theres a lot that we can take away from whats happened before.

As he gave BusinessWest a tour of the Ludlow complex, Delude stopped the car at several locations to point out both opportunities and challenges, and there are several of both.

In the latter category, he referenced a warehouse, circa 1914, that housed finished product and was, in its day, the largest jute warehouse in the world. It is eight stories high, but shorter than the neighboring five-story mill because each level outfitted with some of the first concrete floors used in this country due to the excessive weight of the twine is only eight feet high.

This will limit re-use possibilities, but there are several options, said Delude, who said the building is one of many he would like to preserve if possible.

The stockhouses present another challenge for reuse, he continued, noting that their size (roughly 6,000 square feet each) and shape do not lend themselves to easy re-use. Meanwhile, they stand between the mill complex and the riverfront, and one of Deludes goals with this project is to make more and better use of the river.

For more than a century now, access to the river has been blocked, he said as he pulled the car to a spot along the bank. People can see it, but they cant get to it; we want to change that.

Development opportunities abound at the site, said Delude as he drove down State Street to the large, undeveloped stretch of the mill property, which winds along the river and eventually abuts Ludlow Country Club. The 70-acre site sits across from an attractive residential neighborhood, but Westmass industrial parks have shown they can live in harmony with such areas, he explained.

This is the case in Agawam, where a business park built on what was once Bowles Municipal Airport abuts several residential streets. Weve shown that we can successfully co-exist with neighborhoods like this one.

There are more than 60 buildings on the Ludlow site, said Roberts, who told BusinessWest that Westmass will attempt to reuse all those where preservation makes sense. In those cases where it doesnt, the agency will pursue what he called deconstruction a word he preferred to demolition and reuse the bricks and other building materials in a broad effort to maintain the look and feel of the historic jute-making complex.

The next steps in the process of making the vision for the site reality are to finalize purchase of the property which is expected to take place over roughly the next year and complete what Delude called a business plan for the project.

This involves gauging what is feasible with regard to what he considers to be perhaps five distinct phases, and coordinating a plan for how and when to proceed with each one. Were going to spend the next 18 months testing theories and principles, he explained. Were going to determine what we can do, and what we should do to create jobs and opportunities for this region.

Overall, Delude said the sites location only a few minutes from Turnpike exit 7 in Ludlow and various amenities add up to an attractive, and sustainable, economic-development initiative that will make the clock tower building as much a part of the towns present and future as its past.

Its such a significant feature of the town, he said of the landmark. But what it meant for the region, not just Ludlow, was vitality and energy, and it can be that again.

Not a Run-of-the-mill Project

As he talked about the Ludlow initiative and how he envisions it progressing, Delude compared it in many ways to the Agawam Industrial Park.

Although much different in nature, the sites are similar in size, at least with regard to how many square feet of industrial and commercial space each can accommodate. Meanwhile, the Agawam project has taken roughly 20 years to develop and reach near-full occupancy and roughly the same is expected for the Ludlow site and both locations necessitate industrial park development in a mostly residential setting.

The Agawam park now boasts more than 2,000 jobs and contributes millions in tax revenue to the community, said Delude, adding that, if this rate of performance can be matched in Ludlow, Westmass will go a long way toward making an impact that will be on a smaller scale than that made by Ludlow Manufacturing Associates, but perhaps just as significant.

An image to rival that lithograph will probably be two decades in the making and thats if all goes as planned but if things develop as Delude believes they will, it might be just as powerful.

George OBrien can be reached at[email protected]