Breaking Ground

Amherst Farmer Refines Method of Growing Plants Without Soil

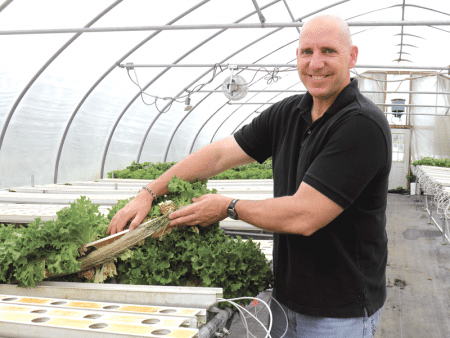

Joseph Swartz shows off the roots of lettuce plants growing hydroponically in his greenhouse at Swartz Family Farm in Amherst.

Although the idea may sound farfetched, it’s not a fantasy. Instead, it’s one of many projects that Joe Swartz of Swartz Family Farm in North Amherst has accomplished in recent years.

Swartz is a master hydroponic gardener who has taken the industry to new heights. In fact, the New York City farm he designed for Skytop Vegetables was the first in the nation to be grown on top of a public-housing structure. “I did the early sketches on my kitchen table in Amherst,” he said, as he talked about the 8,000-square-foot rooftop farm that opened in February 2013, and provides fresh, nutritious vegetables to residents of the building and neighborhood as well as patrons of nearby restaurants and markets.

Swartz has gained international recognition as an expert in hydroponics, which is a method of growing plants without soil. They are planted from seeds in holes set in plastic containers and thrive on a nutrient solution dissolved in water that runs beneath them and is recycled after the plants take what they need from it.

Swartz has 28 years of experience in operating a year-round, pesticide-free, hydroponic vegetable-and-herb facility in Amherst. It’s a field he entered long before most people thought about where their produce came from and environmental concerns created a demand for locally grown vegetables and fruits.

As a result, Swartz has become a leading expert in hydroponic system design, high-end crop production, biological pest control, system troubleshooting, and much more, and has spoken all over the U.S. and in many foreign countries about his groundbreaking work.

“It’s very gratifying, and when I think of the evolution of all that has happened in the industry since I began my farm, it’s mind-boggling,” he said, adding that he gave a recent lecture at a national conference in Las Vegas and was just invited to speak at a major agricultural conference in England.

The concept of transforming unused rooftop space into a hydroponic garden has many environmental benefits, which include water conservation. “All rainwater that strikes a flat roof has to be channeled into the city’s stormwater systems, and most systems in U.S. cities are completely overwhelmed; one inch of rain that falls on an acre equates to 27,000 gallons of water,” Swartz explained, adding there are more than 15,000 acres of rooftop space in New York City alone.

“But a rooftop greenhouse has gutters on all sides, and rainwater is sent into an underground tank, where it is filtered, cleaned, and used for farming,” he went on. “So it allows us to take a waste product and convert it into food in a very sustainable manner.”

Benefits also accrue from the fact that a rooftop greenhouse shares synergy with the building. Sun that hits the roof and requires the building to be cooled is absorbed by the crops, which also absorb heat from the building in winter, preserving it rather than having it simply go into the atmosphere, Swartz said.

In addition, the system takes heat from the building’s smokestack and uses it to heat the greenhouse. “It capitalizes on heat that is normally wasted. Plus, the greenhouse has thermal curtains that hold the heat in at night. So it’s a win-win situation for the building owner and the owner of the garden,” he told BusinessWest. “It also produces jobs for local residents without many job skills and allows people in the neighborhood to get fresh, nutritious food that doesn’t have to trucked in from thousands of miles away.”

And rooftop gardens, which are rapidly expanding across the country, also provide inner-city children with agricultural knowledge. “We worked with a local school in the Bronx, and a frightening number of children thought milk was made in a manufacturing plant. They had no concept that it came from an animal,” Swartz said. “And most of the people in the neighborhood got their food from a small convenience store and did not have access to nutritious, locally grown vegetables and herbs until the garden was created.”

Growing Venture

Swartz Family Farm has been in business for 100 years, but Swartz likes to keep a low profile, and there are no signs to mark the entrance to his home, greenhouses, and acreage on 11 Meadow St.

“My grandfather Joseph and his wife Anastasia purchased 40 acres and started this farm after they came here from Poland in 1919,” he said. The couple grew mixed vegetables and tobacco and raised their family on the site.

Swartz’s father and uncle took the farm over in the ’50s and turned it into a large-scale potato-growing operation. In addition to growing potatoes on their farmland, they rented land in Hadley, Amherst, Sunderland, Hatfield, and South Deerfield; at the peak of their business, they were raising 300 acres of potatoes.

But his uncle died in 1970, and in the ’80s, the price of land became exorbitantly expensive due to extensive residential development in the area. “As my father got older, he scaled back to the 40 acres here.”

Swartz was in high school when he realized farming his family’s land on a seasonal basis was not a viable option because the economy was booming and seasonal help and additional farmland for crops were unavailable. “So I decided I had to look at a small-scale, very intensive type of agriculture,” he said.

His interest in controlled environmental agriculture, or hydroponics, began in 1985 when he was a student at the Stockbridge School of Agriculture at UMass Amherst. He learned the system had been pioneered in Holland and had expanded to the United Kingdom and Spain, where hydroponic greenhouses were operational year-round.

“The same nutrients you would normally apply to a field are dissolved in water,” he noted. “The plants take what they need, and the rest is recaptured and reused. It only requires 10% of the water needed for conventional agriculture, so it is a very environmentally friendly form of agriculture.”

However, the university did not have a program where Swartz could learn how to implement this growing method on a large scale. But he was fortunate enough to meet a retiree living in Ashby, Mass. who was running a small greenhouse growing hydroponic flowers. He had been the lead associate at Cornell University’s research center on Long Island, was originally from Holland, and had pioneered a large portion of the hydroponic technology that was being implemented in the U.S.

Swartz received valuable guidance from him on how to produce a premium product year-round inside a greenhouse on his property.

But when he began building a greenhouse on his family’s land and shared his plan with local farmers, they thought the idea was ridiculous.

“I was considered a crackpot. We have a very tight-knit agricultural community in the Valley, and no one understand why I would grow produce in water when there was beautiful soil here,” he recalled. “But for me, it was a necessity.”

The day after Swartz graduated from UMass, he began working in his new, 5,000-square-foot greenhouse. “At that time, there were 13 hydroponic farms in the state, and today we are the only one of them that is still in operation — we have the longest-running hydroponics farm in the Commonwealth,” Swartz told BusinessWest, adding that he also grew seasonal vegetables on the farm’s 40 acres and sold them to traditional markets.

But his greenhouse thrived. “In my first year, I produced more than 80,000 heads of Boston lettuce in it. In a field, you only get 5,000 heads per acre, and you can only plant one crop. But I was able to plant year-round,” he said, explaining that he devised a system where he was continuously harvesting and reseeding in different sections of the greenhouse.

Paradigm Shift

Swartz has continued to produce hydroponic crops at Swartz Family Garden for 30 years. Lettuce has always been a staple, but after his initial success, he built two other greenhouses and soon was shipping 300 cases of sweet basil a week to 42 Whole Foods stores across the Northeast.

About 15 years ago, when hydroponics became more well-known, Swartz delved into consulting work, which was a natural transition, although he continued farming his own greenhouses. “There were very few experts in the U.S. back then, and there wasn’t much information about how to grow hydroponically on a sustainable, commercial scale,” he said.

Over the past five years, as awareness and concern about the environment escalated, the demand for local products began to rise.

“Public awareness changed buying habits, and the demand for urban agriculture began to grow,” Swartz said. “It was a paradigm shift because, before that, food was produced on large commercial farms which were often not even in this country.” In fact, when he first began to sell Boston lettuce, there was nothing but iceberg lettuce in the stores, and there was no demand for any other variety.

About four years ago, Swartz was approached by two men who were starting a company called Sky Vegetables. “They wanted to take the concept of urban agriculture one step further and build commercial farms on flat city rooftops, because there is so much of that space that is unused,” he said.

He became their director of farming, and in 2009 began designing a hydroponics rooftop garden for a new LEED Platinum-certified building in the Bronx that would be used for public housing. Arbor House was completed in 2012, and the rooftop farm opened in February 2013.

“The space was leased for $1 for 99 years, and lettuce and cooking greens such as chard, kale, sweet basil, upland cress, and baby bok choy are grown there. Sky Vegetables operates the farm independently, and the building’s residents have the opportunity to get food from it via a community-supported agriculture program,” Swartz said.

Today, his wife, Sarah, operates their hydroponic farm in Amherst, which sells produce to local vendors such as Atkins Market. Swartz left Sky Vegetables six months ago to consult full-time with growers across the globe. He just finished an ongoing project in Kuwait and is going to Dubai to assist a large-scale farm in replicating a hydroponics system in Singapore. “I need to fine-tune the system before they can expand and replicate it,” he explained.

Limitless Potential

Swartz has more than 49,000 hours of greenhouse production time and has also done consulting work in a variety of settings. This year he has already been to Nassau, Bahamas; Santa Cruz, Calif.; Atlanta; Halifax, Nova Scotia; and Las Vegas.

“Hydroponic gardens range from simple, home-built systems that are outside, to conventional greenhouse systems, to very high-level, computer-controlled greenhouses, to a garden in Nova Scotia that grows without sunlight inside a warehouse, using LED lighting,” he explained. “It’s a 100% controlled atmosphere — and the final frontier is space.”

Indeed, he noted that a colleague, Gene Giachumelli, professor of Agricultural and Biosystems Engineering and director of the Controlled Environment Agriculture Center at the University of Arizona, is designing a hydroponics food-production system for outer space, where one of the challenges is zero gravity.

“It’s a very interesting industry, and hydroponics is the safest food-production method possible,” Swartz said, as he stood on his family farm, gazed at his greenhouse, and recalled his own history.

“My father and many other people thought I was crazy when I started this. But I have taken the farming techniques I developed in the Valley and am working with growers across the globe today,” he said, adding that pesticides are not needed, and “you cannot get safer food products.”

That endeavor has no limits, and Swartz will continue to grow his own business as well as help other people across the world create farms without soil, sunlight, and other factors — in the process transcending what any farmer could have imagined several generations ago.