Epic Proportions

Indian Orchard’s Titanic Museum Keeps the Memories Alive

It’s hard to imagine now, says Ed Kamuda, but there was a time when people just weren’t that interested in the Titanic.“In 1912, there were some books, and there was a one-reel picture starring Dorothy Gibson, an actress who was one of the survivors,” Kamuda said of the year when the great ship sank, “but then interest dropped off. In the 1950s, with Walter Lord’s book, A Night to Remember, and then the film of the same name, there was some more interest, but that soon went away, too.”

But it was that movie, shown in the Grand movie theater in Indian Orchard, that set the young Kamuda on the course that would define his life.

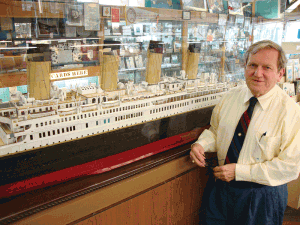

As founder of the Titanic Historical Society, he is known worldwide as one of the leading authorities on the most legendary maritime disaster. From his small storefront on Main Street, across from the theater his family owned that started it all, he, his wife, and his sister maintain the Titanic Museum. While the museum is neither big nor flashy, Kamuda’s life’s work is regarded as one of the most important repositories for survivors’ narratives, and also has its share of treasures from the fabled vessel.

He said that, as a young man, he read the story “A Great Ship Goes Down,” published in a Reader’s Digest-style collection of stories, and when the 1958 movie came to his father’s theater, along with it was sent a ledger of production information for the film.

“In the back,” he said, opening the old book before him, “you see the names and addresses of the known survivors. The thought was that, if you were a theater manager, you might want to see if there was a local survivor to come to the opening night of the film for publicity. I contacted many of them, and they were all very surprised that anyone was interested in them.”

Kamuda began correspondence with many of those survivors, and when Walter Belford, chief night baker aboard the Titanic, passed away in 1963, he found out that his New York City landlord threw out most of the man’s possessions.

“When I heard this, I was very upset,” Kamuda said, “and at that moment I decided, ‘I’m going to form a museum to preserve all of those precious memories.’ That’s how all this came about.”

Taking a Bow

Walking around the small but densely packed space, Kamuda pointed out numerous treasures that relate not only to the Titanic, but also to the White Star line, owner of the ship, and her sister ships, Britannic and Olympic.

But what brings people from all over the world to the museum is the namesake collection: among many other things, a square of green wool rug from a first-class stateroom, taken before the ship left the Harland and Wolff yards in Belfast, Ireland; a small flag taken from a lifeboat; a rivet punching from the hull; original shipyard plans; John Jacob Astor’s wife’s lifejacket, given to the chief medical officer of the Carpathia, famous for rescuing the lifeboats; and the message which never made it to the ship’s bridge warning of ice.

“As survivors saw their lives coming to an end, they wanted someone to take care of their legacy,” said Kamuda as he explained much of the collection’s origins. “So they’d send it off to us. Or their children wanted a museum to take care of it.

“We don’t have any artifacts from the site on the ocean floor,” he emphasized, “because we feel that is hallowed ground, a gravesite, and should be left alone.”

It is the narratives the museum holds from those that were aboard on that night that carry a great deal of emotional resonance for Kamuda. He opened one of his Historical Society’s publications, The Titanic Commutator, to show a letter written to him by Frederick Fleet, the lookout in the crow’s nest on the starlit night that tragedy fell upon the Titanic.

In an old-fashioned hand, the letter informs his “Dear Friend” Kamuda that his correspondence will have to wait until he finds a new place to live, as his wife has just died and his brother-in-law and he “cannot agree.” It is postmarked just days before he took his own life.

Among Kamuda’s treasures are photos that Fleet had sent of his fellow seamen, along with two drawings that the sailor made: one of what the iceberg looked like on the horizon, and, alongside that, how it soon towered over the ship. It was Fleet who shouted the words, “ice ahead, sir.”

Among those who have benefited from Kamuda’s and his society’s expertise is James Cameron, director and producer of the 1997 epic film Titanic.

His production assistants were in frequent communication via e-mail with the museum, fact-finding myriad details to make the film as historically accurate as possible.

When it came time for filming in Mexico, Kamuda’s wife, Barbara, said it would be a fitting tribute for her husband to have a role in the film. It was Hollywood, after all, that had a hand in bringing the Titanic to Indian Orchard.

Both were offered bit parts, as well as society historian Don Lynch. The Kamudas’ Tinseltown time came in a scene out on deck with Kathy Bates and Leonardo DiCaprio. It was eight takes long due to the actress cracking jokes, he said, but the real shock came when he and his wife stepped on set for the first time.

“Cameron stopped production and called out to everyone there,” Kamuda said. “‘I want you to see these two people coming out here,’ motioning toward us. I looked at my wife and said, ‘what the hell is going on? Did we do something wrong?’

“He then said, ‘but for these two people, we wouldn’t be here today. They help to keep the memory alive.’ And then he said, ‘OK, let’s get to work!’”

Even Keel

Kamuda said that what keeps him going all these years is knowing that the stories from those people that were part of the Titanic will be preserved for all time.

“There will be people who walk in, look around, and ask, ‘that’s it?’” he said. “They don’t get that you can spend hours in here. You have to appreciate it. There’s so much to read. This isn’t a Disney-style museum.”

Some of the museum’s artifacts are lent out to a larger, more showy museum in Branson, Missouri — where one enters into a full-sized ship from the iceberg, and which has recreated the famous grand staircase — and Kamuda says that proceeds from that arrangement and loans to other museums are ultimately going to help in the creation of a larger facility here in Springfield.

As he tells how the society’s plans for the 100th anniversary of the Titanic disaster will involve not just a convention here in Springfield, but also the commemoration of a monument, currently in a fund-raising stage, planned for the city, it’s clear that his life’s work is a true calling.

“This is the mecca for Titanic history,” he said. “So many people have written books, or made films, and they all come to us for information.”

With the last survivor, Millvina Dean, now gone (she passed away last year), Kamuda said that his museum is one of the last things to remain for those whose fate was tied to the epic story of the Titanic.

“Luckily we have those interviews with them here,” he said. “Their story is history.”