STCC Project Is Historic on Many Levels

Centuries in the Making

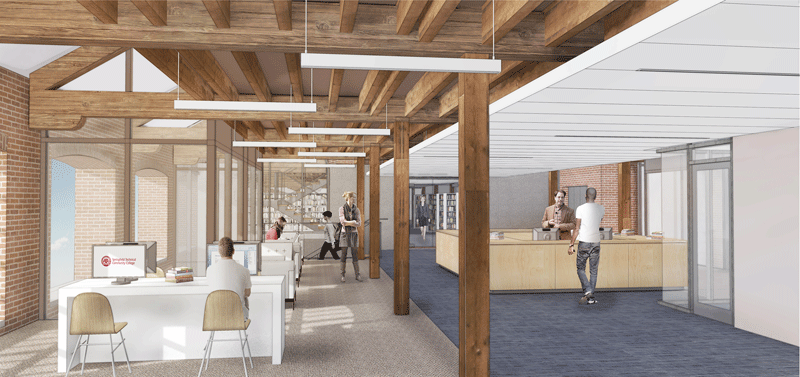

Rendering of the library in the renovated Building 19. (Ann Beha Architects)

As Springfield Technical Community College commences a year-long 50th-anniversary celebration, a landmark historic restoration project is taking shape — with the accent on ‘landmark.’ So-called Building 19, a 700-foot-long warehouse that predates the Civil War, is being converted into a campus center, a project that will enable the past and present to co-exist in a powerful fashion.

Tom Duszlak says he’s heard all the rumors.

Actually, they’re more like legends. And some of them are fact.

Like the story related to him about the construction crews that, while working to set oil tanks at what is known as Building 32 on the campus of the Springfield Armory more than a half-century ago, unearthed bones belonging to soldiers from the War of 1812.

“They were digging out the floors to put in these storage tanks when they came across some skeletons,” said Alex Mac-Kenzie, curator at the Armory, noting that, in the early 19th century, Building 32 was a barracks. An influenza outbreak swept the region, killing several soldiers, and they were buried right on site.

There are many other stories concerning people finding bones, uniform fragments, tools, and other items on the grounds during various building projects, and the validity of some tales is a matter of conjecture. But Duszlak says there is absolutely no debating the underlying (pun intended) sentiment regarding this historic site, chosen more than two centuries ago by George Washington: that one never really knows what might be found in the ground there.

Tom Duszlak says the Building 19 projects comes with a healthy list of challenges, including uncertainty about what crews may unearth at this historic site.

And that’s just one of the many challenges confronting Hartford, Conn.-based Consigli Construction, which Duszlak serves as project superintendent, as it takes the lead role in an ambitious, $50 million project to convert the cavernous structure known as Building 19 (right next door to Building 32) into a new campus center for Springfield Technical Community College.

Actually, crews have already unearthed some “artifacts” (Duszlak’s word) while undertaking some extensive infrastructure work at the site.

“We found some cow bones and a few pieces of metal that might be part of an old piece of manufacturing equipment,” he said, adding that the ‘we,’ in this case, is mostly a reference to the full-time archeologist — hired by the National Park Service, which manages the Armory site — who is on hand whenever crews dig deeper than four inches.

And there’s been a lot of digging to date, with most of it still to come — this building is 700 feet long, said Duszlak, adding quickly that, while a small part of him wants to unearth something intriguing — “I’d love to find an old cannonball or something like that” — the project superintendent in him is more pragmatic and fully understands that finding ordnance, let alone old soldiers’ bones, would mean potentially lengthy delays in an already-demanding project.

As mentioned, the fact that the Armory grounds could be described collectively as an archeological site is just one of the challenges facing Consigli, Ann Beha Architects, the state Division of Capital Asset Management and Maintenance (DCAMM), and STCC administrators as they proceed with this project. Others include the reality that this mammoth initiative must play itself out on a crowded college campus populated by 8,000 students and another 1,000 faculty and staff; that the site’s infrastructure, complete with some brick water lines, is quite old and mostly in need of replacement; that the work is taking place, in part, on a road system designed for horses and buggies; and that, with every bit of digging or restoration work, unforeseen problems may arise.

But the challenges ever-present in this project to convert what amounts to a 19th-century warehouse for walnut gun stocks into a thoroughly wired, 21st-century community-college nerve center, are also what make it so intriguing, and so rewarding.

“There’s history all around you here,” Duszlak noted. “Working in an environment like this — a functioning college campus — is logistically difficult, and this is demanding work. But it’s fun to blend the past with the present.”

Architect George Faber stands in the center of historic Building 19 as a multi-faceted restoration effort takes place around him

George Faber, project designer with Boston-based Ann Beha working on the Building 19 project, agreed.

“One of the main design goals here is respecting the building as it is, and as it was, while making it modern for contemporary use,” he said. “We’re obviously not trying to replicate the old; we’re trying to complement it in a way that might even teach someone about the history of this campus.”

For this issue and its focus on construction, BusinessWest talked with Duszlak, Faber, and others involved with this project — which is historic in every sense of that word — to get a sense for all that’s involved with an endeavor that has been centuries in the making — quite literally.

History Lessons

As he and others gave BusinessWest a quick tour of the Building 19 construction site, Faber stopped to point out a few of the original wooden shutters, or louvers, that graced the dozens of arches and curved windows that give the structure its unique identity.

Crews will replicate those features, and be meticulous in their efforts to match the material, look, and original color — something that was difficult to determine, Faber explained, adding that some of the originals that are in good shape will be restored and put back in place.

Thus, there will be an effective blend, or co-existence, if you will, of old and new, which, in a nutshell, is what this project is all about.

In construction circles, this kind work is considered a specialty, both for the architects and the contractors. And both Consigli and Ann Beha Architects have deep portfolios of similar projects.

Consigli, for example, has handled a number of projects in the category it calls ‘landmark restoration,’ including one unfolding just a mile or so, as the crow flies, from the STCC campus. This would be work on the headquarters building of the former Westinghouse complex on Springfield’s east side, now the home of the massive assembly plant being built by Chinese rail car maker CRRC MA.

Other projects in the portfolio include an elaborate restoration of New York’s historic Capitol Building, which dates back to 1867; restoration of the Smithsonian American Art Museum’s 19th-century Renwick Gallery; renovation of three historic buildings on the Trinity College campus in Hartford; and work to restore the exterior envelope of Maine Medical Center in Portland, opened in 1874.

Ann Beha Architects, meanwhile, has undertaken many historic preservation and restoration initiatives on college campuses, including MIT, the University of Chicago, Yale, Bates, and others.

“Ann Beha started her career doing historic-preservation work, so it’s always been a big focus for us,” said Faber, referring to the company’s founder. “We’ve done work in museums, colleges, and other institutions.”

This is the first project for both firms on the STCC campus, which means crews have undoubtedly absorbed a number of history lessons — and heard a number of stories, like the one about soldiers’ skeletons being unearthed — while taking on this ambitious undertaking.

They know, for example, that the buildings they’re using to stage and manage this project (as opposed to the traditional trailers that dot most construction sites) were once officers’ quarters dating back to the Civil War.

By then, of course, the Armory had accumulated almost a century of history, having opened its doors in 1777. Chosen by Washington in part because the site would be safe from naval bombardment — Springfield is located just north of a waterfall in Enfield that cannot be navigated by ocean-going vessels — the Armory did, nonetheless, come under attack. Sort of.

This was Shays’ Rebellion in 1787, a quickly crushed insurrection — one that nonetheless helped inspire the Federal Constitutional Convention — led by Pelham farmer Daniel Shays, a Revolutionary War solider who had gathered a number of rebels who, like him, were upset with their financial plight and thus the state’s government, and decided that seizing the arsenal in Springfield would certainly get someone’s attention.

Since arriving on site several months ago, crews might also have been learned about John Garand, the legendary Canadian-born firearms designer employed by the Armory who created the famous M1 Garand semi-automatic rifle, which Gen. George Patton would call “the greatest battle implement ever devised.”

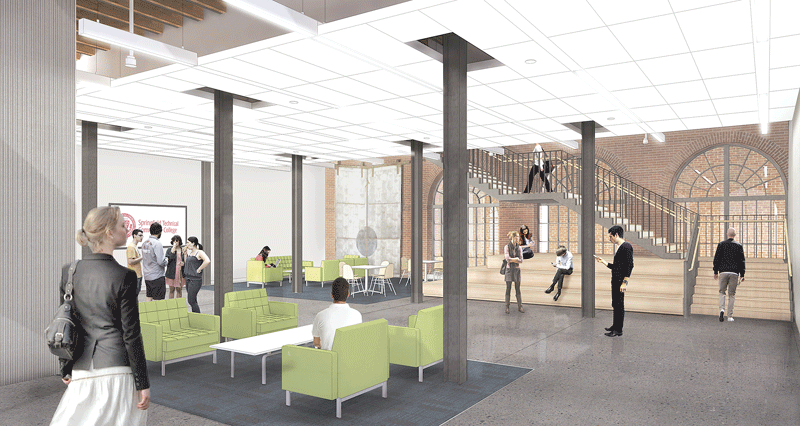

Above, Building 19, as seen in the early 1930s; below, a rendering of what will be called the Learning Commons. (Ann Beha Architects)

At its height, during World War II, the Armory would employ more than 14,000 people making M1s and a host of other weapons, but two decades after that conflict ended, Defense Secretary Robert McNamara — earning himself an ignominious place in Springfield history — determined that private defense contractors could manufacture the nation’s weapons. He ordered the decommissioning of the Armory, putting more than 2,000 people out of work, a decision that would damage the local economy but also pave the way for the site’s next life.

Indeed, a group of area leaders, including then- (and also future) Springfield Mayor Charlie Ryan; Edmund Garvey, then-director of the Springfield Technical Institute; state Rep. Anthony Scibelli; and Springfield industrialist Joseph Deliso Sr. pushed for legislation that would create a “two-year college of technology.” (Their efforts, and their legacy, will be celebrated at STCC’s Founders Day festivities on Sept. 9, the first in a year-long series of events to mark the college’s 50th anniversary.)

Blueprint for the Future

The Founders Day speeches will be delivered in the gym in Building 2 on the STCC campus (a.k.a. Scibelli Hall). Those taking them in will need to look only a few dozen yards to the north to see the beehive of activity at ‘19,’ as it’s known colloquially.

Unlike other Armory structures, especially its main administration building, now named after Garvey, 19 has not had any significant role with the college since it was formed, other than as a warehouse for equipment that was no longer needed but couldn’t be discarded.

All that is about to change, though, and in a big way.

Indeed, the renovated structure, due to open in the fall of 2018, will be home to a wide array of offices and facilities now scattered across the campus, including the library, admissions, registration, financial aid, the bookstore, the welcome center, student government, the parking office, health services, student activities, a café, the IT help desk, meeting and conference space, and much more.

This collection of facilities will be called the Learning Commons, and if that sounds like a lot to put under one roof, remember that the roof of 19 covers a building longer than two football fields, complete with the end zones, and there are two full floors and a loft third floor.

As noted, converting a structure that large, built a century and a half before the Internet was conceived, 40 years before the lightbulb, 35 years before the telephone, and 80 years before air conditioning (and thus not designed for any of the above) — all while maintaining its original architectural elements and being on the cutting edge of energy efficiency (LEED Silver designation) — will be a stern challenge.

This will require, as Faber noted earlier, coexistence of the old and the new, because they’re both vital, but for different reasons.

“From a design standpoint, it’s really about respecting the tradition of the building,” he explained, adding that this can and will be done, while also making the facility ‘green’ and state-of-the-art with regard to information technology.

Duszlak said there are a number of stages to the project, many of which will be carried out concurrently.

Late this spring, work began in earnest on infrastructure, what he called the “enabling phase,” including water, sewer, and electrical lines. He added that crews made the very most of the three months when the student population is greatly diminished, with the goal of minimizing disruption when they return this week.

Maureen Socha, director of Facilities for STCC, said the project represented an opportunity for the college and DCAMM to greatly improve an aging, and often failing, infrastructure system, one that has been seized.

“A lot of our infrastructure is original to the Armory — we still have brick pipes and clay pipes everywhere,” she explained. “This was a huge opportunity to upgrade that system.”

An architect’s rendering of the forum section of the renovated ‘19.’ (Ann Beha Architects)

While infrastructure work continues on a smaller scale, restoration work on both the exterior and interior of the building have commenced, with the goal of preparing the structure for the extensive build-out work that will follow to create offices, a library, a café, and gathering spaces out of what was a cavernous warehouse.

“The roof gets brought up to current code, the second floor gets brought up to code, a lot of the existing joists get reinforced with structural steel,” Duszlak said. “There’s new elevators to be put in, new mechanical shafts to get cut through the building … a lot of it is just upgrading the skeleton of the building to get it ready for the tradespeople to create the spaces.”

There are many elements to this blend of restoration and renovation work, ranging from cleaning and repointing the hundreds of thousands of bricks to matching (after first determining) the original color of those louvers.

And in a way, the louvers are a microcosm of the project’s many challenges and the huge amount of research and even lab work that goes into such preservation and restoration efforts.

“We had a consultant who took paint chips off the building, took them to a lab, and, through use of a high-powered microscope, was able to pick out the different layers that had been painted over time,” he said. “We found four or five different colors layered on top of one another.” (A darker brown has been declared ‘original.’)

Research has involved poring over hundreds of old photos from not only the Armory but the Library of Congress, he went on, adding, again, the goal is a modern, energy-efficient facility that nonetheless pays respect to the building’s historic look and role.

Soon, work will commence on a 3D coordination of the space, said Duszlak, adding that this will enable crews to make sure all the mechanicals — plumbing, electrical, and HVAC services — are properly coordinated and there are no conflicts.

“There are a number of architectural elements that Ann Beha is concerned about,” he explained. “They want to keep a lot of the timbers exposed to give it some of the old-feel look, but keeping that much square footage exposed, and the ceiling, it limits where you can put duct work and electrical, which adds to the challenges and emphasizes the importance of the 3D coordination.”

Past is Prologue

Looking ahead, Duszlak noted that there is considerable digging (maybe 75% of the total for the project) still to be undertaken at 19 and its larger footprint.

“We have new structural upgrades that we have to dig foundations for,” he explained, “and we have electrical utilities that run the complete 715-foot length of the foundation. There’s new under-slab plumbing and drainage that services new bathrooms … we’ll be doing a lot of digging four to seven feet down.

“So there’s the potential for finding a lot of really cool artifacts,” he went on, adding that, while he doesn’t want to encounter anything that might hinder progress, he wouldn’t mind creating some new stories — or legends.

That’s what can happen when the past, present, and future come together in such dramatic, and historic, fashion.

George O’Brien can be reached at [email protected]