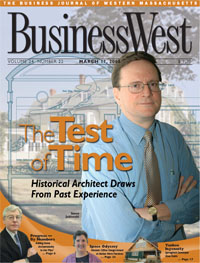

Test of Time

Historical architect draws from past experience

The act of giving old buildings new life is a discipline that requires endless study and research, but also creative thinking for architects whove chosen to focus on this aspect of their field. Stephen Jablonski is one such professional, whose work can be seen across the Pioneer Valley and beyond. He says many think his line of work is staid and stuffy, but his portfolio of projects in Western Mass. shows that it is anything but.

Architect Stephen Jablonski works out of one of the oldest homes in Springfield, the Alexander House, built in 1811.

It was recently moved to accommodate the new federal courthouse on State Street, and some feared that the building wouldnt make it to its destination. But with nary a crack in sight, it stands original columns, windows, and elliptical, cantilevered staircase intact.

This building is in line with the work that I do, said Jablonski, who has focused on a specialty known as historical architecture, a specific niche within the industry, for the majority of his career. A lot of architects want to knock things down to show what they can really do, but I slow down and explain what a building like this is made of, and why its important.

The Alexander Houses spiral staircase, for instance, is unique because it uses no supports the design alone makes it sturdy and because its the only known elliptical, cantilevered staircase in the city.

Its also just one of many examples of intriguing design that Jablonski can offer when discussing historical architecture. His is a discipline that draws from countless architectural styles and implements an equally large number of methods, but still, Jablonski said his field is one that has taken some hard knocks.

The perception is that historical architects are not cutting-edge, he said, or that were frumpy and boring and wear bow ties. While I do have a large collection of bow ties, the perception is not accurate. There is an innate creativity associated with historical work, and there are plenty of craftsmen to recreate historical structures.

And while historical architecture is often seen as a specialty that recreates the past but shies away from devising anything new, Jablonski said this, too, is a fallacy. The field is broad, including historical restoration and renovation, but also the design of, additions to, and replacements of buildings. Its never the same, he said, and every job is a new challenge that opens up a world of possibilities.

When creating something new, most of society tends to go in a banal direction, he said. It may be new, but often, new buildings are designed to look more like everything else, not less.

Whats more, Jablonskis specialty sometimes makes him an anomaly within his own profession.

As an architect, everything you do is focused on change, but how things change is really the essence of historical architecture, he said. Building standards vary from property to property; some are broad-brushed, and some are very strict. The guidelines are necessary, especially because historical renovation or replication can be very expensive. Thats where the real creativity comes in.

The Nuts and Bolts

As an historical architect, Jablonski has a set of specific concerns that he must consider with every project. Theres considerable research to do before even setting pencil to plans, for instance, and its aimed at developing a keen understanding of how a building was constructed, what its been used for in the past, and how many changes have taken place within its walls since they were erected.

You have to appreciate what a building was designed for, he said, and look for any changes in use. You also need to make a good record of whats there; often, existing drawings are incomplete, and in any case, you dont want to confuse the map for the territory.

Further, properties that have been placed on the National Register of Historic Places offer their own design challenges, including standards set forth by the Secretary of the Interior. These center on preserving the historical integrity of a building by requiring the use of in-kind materials, for example (a copper roof can only be patched with copper; finding the right storm window can take months).

Jablonski attended the School of Architecture at Syracuse University and said that, even as a student, he had to forge his own path to study historical buildings and their design.

Syracuse has a very modern program, so I more or less had to train myself, he said. We were discouraged, for instance, from using color when drafting plans, whereas I always wanted to use color in my designs. I never wanted to wrap a building in steel or something to make a statement. To me, theres something about a patina of age that adds character that is real.

His passion for history remained strong through college, and Jablonski began his career in Boston in the early 1980s, later relocating to Northampton in 1987 and practicing there until 1994, when he relocated again to Springfield. Today, Jablonskis firm includes three employees, and works frequently with other architects, drafters, and craftsmen in the area. Their renovations and restorations can be seen across Western Mass., and the company is beginning to expand its reach toward the eastern part of the state and into Connecticut.

Jablonskis first historical project in the area was at Holyokes Wistariahurst Museum, a National Historic Register property. The work began with restoration of the Bell Skinner bedroom, but over the past decade, his firm has completed interior and exterior restoration to the museums siding, paint schemes, roofs, and conservatory.

The Skinner bedroom renovation was followed by an interior renovation project at the Sacred Heart Church in Springfield, restoring floor patterns and long-faded color schemes. That led to a particular professional focus on places of worship for the firm.

Id never worked on a big church before, but I liked the approach, he said. The parish didnt want to change their church, but rather embellish what it already had, and maintain its character.

His work at Sacred Heart led to similar projects across the region, including the Holy Spirit Chapel at St. Michaels Cathedral in Springfield, the Old First Church in Holyoke, First Congregational Church of South Hadley, and Worcesters Hadwen Park Congregational Church.

Jablonskis calling card can be found in many other locales, too. His portfolio includes the Latino Professional Building in Holyoke, the Barney Carriage House at Forest Park, the Brennan and Admissions buildings at Springfield College, and the Museum of Fine Arts at the Springfield Museums.

In all of these projects, said Jablonski, close attention was paid to the use of lasting and traditional materials, natural light, custom woodwork, well-thought-out circulation, and blending old with new. Energy efficiency, affordability, and the ability to stand up to wear and tear are also important considerations, as in any architectural endeavor, which brings Jablonski to another defense of his trade: the intrinsic green qualities of historical construction.

The big thing now in the building industry is going green, and in my mind theres nothing greener than preserving what you already have, he said.

A City of Stories

Others are beginning to understand this, and while the surge in interest regarding historical architecture of late is helping to expand Jablonskis radius of influence, he said Springfield provides plenty of work.

There arent too many cities like Springfield, of this size with world-class buildings, he said. It looks the way it does because of the people who came here, often to manufacture things. There is no predominant architectural style because of the multitude of periods of growth we see Greek revival, neoclassic, arts and crafts my job includes not just architecture, but making sure people understand the regions resources, especially when theyre feeling down on their luck.

Jablonski said that in Springfield, as in many urban centers attempting to spur a rebirth, the first instinct of many is to raze older buildings that are long past their heydays.

People dont see these properties with the eyes that I see with, he said. Does Springfield have some dust on it? Yes, but I urge people to understand that once a building is gone, its next to impossible to recreate what we once had.

Theres a lot of talk about this city as a glass thats either half-full or half-empty, he continued. I see many of the same problems other people cite, but from my point of view, the glass is more than half-full, and its a beautiful glass.

Currently, hes in the middle of a project that speaks to that belief, designing what will be the newest addition to the Springfield Quadrangle the Museum of Springfield History. Slated to open in 2009, the facility will be located in the former telephone operating building on the corner of Edwards and Chestnut streets, and will house such firsts for the city as the GeeBee plane, a Silver Shadow Rolls Royce, and an original Indian motocycle.

This project is the type of work I love to do, said Jablonski. But its also the first time that the museums have expanded outside of the perimeter of the Quad, and the first new museum to be constructed since the Depression.

He added that the project includes both renovation aspects and new construction.

Were finalizing drawings for an addition now, and renovation to the existing building is about 50% completed, he said. Were adding a lot of vertical space and not a lot of square footage, but this will still be the largest exhibit space at the Quad.

He noted that the Museum of Springfield History will also offer a new type of museum experience to the city, its residents, and, most importantly, visitors to the region.

This is going to be totally different, because it will attract the male population, Jablonski explained. The museums do an excellent job catering to many different groups, but theyre pretty much maxed out on women and kids. With the cars, airplanes, and guns that are part of Springfields history on display, the missing population can be drawn in, as we showcase what has also been a missing part of Springfields story.

A New Way of Seeing Things

For Jablonski, the project couples an important mission with a rewarding architectural challenge, creating the perfect kind of historical project.

Its a combination of the architecture I love and the opportunity to do something important in the city where I make my home, he said.

He can see the project from his second-floor window at the Alexander House as well, in addition to a handful of others hes completed, and a few at which hed like to try his hand.

I think I have a quality product in historical renovation, he said, and I have a constantly broadening scope. One thing I dont want to ever become is isolated, working on plans in the proverbial ivory tower of a locked-up office. Inspiration is critical.

To that end, Jablonski can sometimes be seen strolling the streets of Springfield, pausing at a building and perhaps asking passersby, what do you see?

Jaclyn Stevenson can be reached at