Vet Air Takes Flight in a Meaningful Way

Giving a Lift to Those Who Served

Jesus Pereira founded Vet Air to enable veterans to “fly first class” to appointments at VA hospitals.

Dave Shields remembers that first flight being more than a little bumpy. And the plane’s cabin was even smaller than he’d imagined, and took a while to get used to.

Such sentiments, clearly not meant to convey dissatisfaction or disappointment, were to be expected, though. After all, while Shields was certainly no stranger to flying, his 21 years in the Air Force were mostly spent in and around the giant C-130 Hercules transport plane. In fact, the majority of his time serving in Vietnam was spent at Tan Son Nhut Air Base, just outside Saigon, training South Vietnamese crews in how to maintain the workhorse aircraft, which has now been in continuous use by the Air Force for more than 60 years.

It was his time in the service, which also included a lengthy stint at what is now Westover Air Reserve Base in Chicopee, that explains why Shields found himself in that tiny Cessna 172 just over a year ago. Well, that’s where the story starts.

As a veteran, Shields is entitled to receive care for service-related medical issues at the many Veterans Administration (VA) hospitals around the country (such as the one in Leeds) and healthcare providers affiliated with them, such as Yale-New Haven Hospital.

Diagnosed with cancer in his ear, Shields would eventually receive care at both the VA center in White River Junction, Vt., and Yale-New Haven. Getting to either place from his home in Greenfield, while certainly doable, was logistically difficult and quite time-consuming.

Or not, as things turned out, because of a unique nonprofit organization, based in Holyoke, that had just taken flight, quite literally. Called Vet Air, it recruits volunteer pilots to ferry vets like Shields to VA facilities along the Northeast corridor.

Jesus Pereira, founder, a veteran himself (Army Guard, with a 10-month deployment to Kuwait on his résumé), and one of those pilots, explains its basic mission and the many rewards for those who make it happen.

“These people served our country,” he explained. “This is something we can do for them to make things easier and less stressful for them and treat them like first-class, first-rate flyers. I love doing it, and all the pilots feel the same way.”

Pereira, who learned to fly at a tiny airfield in Turners Falls a dozen years ago, said that, to date, Vet Air is averaging maybe two or three flights per month, and has arranged maybe 60 in all. He has piloted roughly a quarter of them, and has taken Shields to several of his appointments.

He noted that, while the pilots are the ones who actually transport veterans to their respective destinations, it takes, well, an army of supporters, including area residents who support its various fund-raisers, to enable the agency to carry out its mission.

For this issue, BusinessWest took to the air with Pereira to gain some insight into Vet Air and its work, which is uplifting, in every sense of that word.

Plane Speaking

To call the flight from Northampton Airport to the even smaller field in Turner Falls a ‘short hop’ would be to greatly understate matters.

It’s 10 minutes door to door, or runway apron to runway apron, as the case may be. But Pereira, who flew BusinessWest to that small town just east of Greenfield to meet Shields — he was already doing some flying that Saturday afternoon and volunteered to do a little more — made the most of that time as he talked about Vet Air, its mission, and the challenges to meeting it.

Indeed, in between frequent bits of routine discourse with officials at both airports during the flights out and back, he explained that this agency is off to what all of those involved consider a very solid start.

Indeed, while only in business, if you will, for 18 months or so, Vet Air has already helped script a number of poignant success stories.

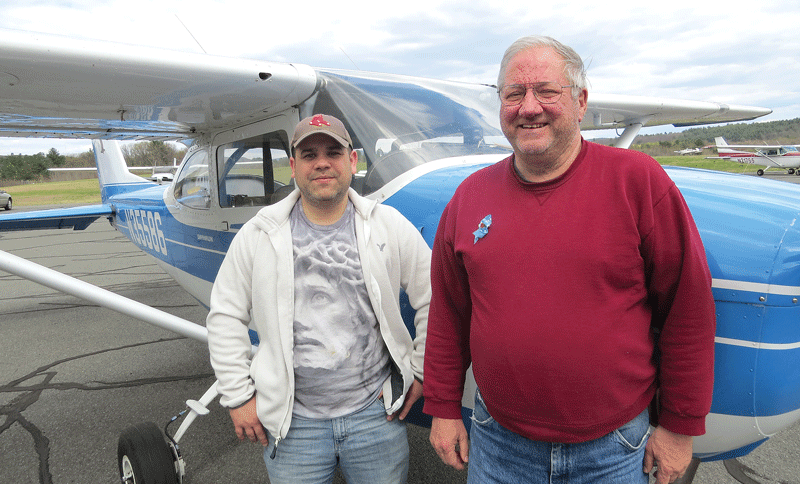

Jesus Pereira, left, with frequent passenger Dave Shields.

For example, there’s ‘Karen,’ an Army interrogator, who was severely injured when a prisoner she was questioning struck her with his handcuffs, breaking her jaw and causing damage to her eyes as well. Vet Air flew her to an appointment at a balance center, where she received specialized care in order to help her with her vision and balance.

Then, there’s Ben Bauman, a Marine from the Bay State who hadn’t been home to see his family in more than two years for personal and financial reasons; Vet Air took him on the last leg of an emotional journey home last Christmas.

To write such stories, Vet Air relies on volunteer pilots, said Pereira, noting that there is a small cadre of them who have made most of the flights to date, usually to the VA facilities in White River Junction and West Haven, Conn., although there have been other destinations as well.

There are three or four Western Mass. area pilots who take part, as well as a colorful individual from Maine who flies a pontoon-equipped plane nicknamed ‘the Moose,’ and handles a number of assignments in Northern New England.

“A lot of them do it because they have the time and means to just go flying,” he said. “But mostly they do it because they recognize the importance of what we’re doing and want to be part if it.”

In many cases, those being transported are veterans in the process of trying to determine if health matters are, indeed, service-related, he explained, adding that this process usually requires several visits to VA doctors, which explains why most Vet Air clients have used the service on multiple occasions.

Many of the servicemen and women who have found Vet Air are veterans of Desert Storm or post-9/11 campaigns in Iraq and Afghanistan, said Pereira, but some, like Shields, served in Vietnam.

Clients simply have to get to the airport closest to where they live, and Vet Air essentially takes it (or them, to be more precise) from there, he told BusinessWest, adding that it arranges ground transportation from the destination airport to the provider in question — usually in the form of a vehicle loaned by one of the airport’s fixed-base operators (FBOs).

There are certainly other means to take such vets to appointments at various providers, Pereira went on, adding that shuttles run between the VA hospitals to take individuals for specialized care at facilities where such services are provided.

“But taking the shuttle can often make a half-hour appointment take all or most of the day,” he explained, noting that a shuttle will make at least a few stops along its route to pick up additional veterans bound for the same destination. And it won’t return home until all those aboard are done with their respective visits.

A flight aboard the Cessna he usually pilots — it belongs to a friend, a flight instructor who lets him take it when he needs it — can cut the trip down to an hour or two.

“We took a woman from White River Junction’s VA who had to go to the Traumatic Brain Injury Center on Long Island,” he noted, citing an example of Vet Air’s primary reason for being. “To drive from Northern Vermont to Long Island is quite a trip. Her appointment was six hours long, and to drive home after that — I don’t think most people could that, so now this becomes an overnight, with all those additional expenses.

“We flew her there and back the same day,” he went on, “and it cost them nothing.”

Soar Subject

This ability to chop several hours off a potentially day-killing visit caught the attention of Shields, whose first involvement with Vet Air centered on bringing it to the attention of other veterans, not securing a ride himself.

“I saw a quick news story about it on one of the local stations,” he explained, adding that his first reaction was to help create awareness. He did so by helping to secure the agency a presence at the annual camping and outdoor show at the Big E in the spring of 2015.

A few months later, though, Shields was diagnosed with cancer and had need for Vet Air himself.

He said there were other alternatives for getting him to the facilities where he was treated, but they involved far more time and logistics.

“This was the easiest way,” he explained. “The [VA] shuttle goes to West Haven, but it doesn’t go to Yale; with Vet Air, there was a courtesy car at the airport that took me right there. It’s a great service.”

Shields hasn’t had to dial Vet Air’s number in several months now, but the nonprofit isn’t far from his thoughts. In fact, he’s become an ardent supporter who has referred a number of veterans to the agency.

And it needs such assistance.

Indeed, as Pereira noted, it takes the help of many people to get that plane in the air and then get the client to the VA facility, said Vet Air’s founder, adding that, while the flyer’s time is donated, there are flight-related expenses — roughly $80 to $120 per hour in the air, depending on the plane used — that have to be covered.

There are other costs as well, he said, listing everything from the landing fees charged by some airports to the modest marketing efforts to bring attention to the agency.

Fortunately, Vet Air’s mission resonates with many individuals and businesses, he went on, citing, as just one example, the FBOs that will often donate a courtesy car, like the one Shields rode in, to get a veteran from the airport to a healthcare provider.

“Once they see what we’re doing and what the mission is, they want to be part of it,” he explained, adding that, moving forward, Vet Air needs more people to become part of its story.

The agency stages fund-raising events such as the recent Mother’s Day Bazaar at the Moose Lodge in Chicopee and a similar gathering coming up for Father’s Day, said Pereira, and also sells T-shirts bearing its logo on its website.

As awareness of the agency grows and need for its services escalates, fund-raising will become an ever-more-important focus, he explained, noting that those who want more information on the agency or wish to help can visit www.vetair.org.

Landing Lights

Like the plane Pereira was flying, Vet Air is certainly small in size as nonprofit agencies go, with a budget that extends to only five figures.

But it is having a big impact on the lives it has entered. That means everyone from the vets sitting in the back seat of that Cessna to the individual flying the Moose; from the families of those veterans to the individuals and related nonprofits who have helped make these flights possible.

Thanks to Pereira’s vision and the help of countless contributors, veterans in need of care are now flying first-class — even if the plane’s cabin is only four feet wide.

George O’Brien can be reached at [email protected]