Generating Interest

Planned United, Rockville Merger Has the Industry’s Attention

Jeff Sullivan, left, and William Crawford will be the president and CEO, respectively, of the ‘new United Bank.’

They’re called MOEs, or mergers of equals.

And while neither the phrase nor the acronym is new to the banking industry, they have become far more prevalent in this sector’s lexicon in recent months as institutions of like size and character have come together to take advantage of many benefits of scale in the currently challenging economic and regulatory climate.

And one of the most watched of these mergers — or mergers in progress, as the case may be — is the one involving West Springfield-based United Bank and Glastonbury, Conn.-based Rockville Financial, which was announced late last fall, and will, if everything goes as planned, be finalized by the end of the first quarter.

The deal, which would create a $4.8 million community institution with more than 50 branches in Massachusetts and Connecticut, is similar to others consummated in recent months in that the banks are of similar size (United has $2.5 billion is assets, Rockville has $2.2 billion), there has been considerable give and take in the negotiations, and the ‘selling’ bank — United, in this case — is actually the one keeping its name, because those involved believe it will ultimately travel better.

But in some respects, this transaction is resetting the bar when it comes to the MOE.

Indeed, expectations are quite high, and industry experts are predicting that this ‘new United,’ as it’s being called, could become a powerful force in the Springfield-Hartford corridor — and beyond.

“This creates a scalable franchise with a competitive advantage among the small to mid-sized banks,” Damon Delmonte, an analyst with Keefe, Bruyette & Woods, recently told American Banker. “There is a real lack of $5 billion-asset banks in Southern New England.”

Meanwhile, David Englander, a columnist with Barron’s, wrote recently that “the merger looks like a good one. When it closes in 2014, the combined bank will have $4.8 billion in assets and more than 50 Massachusetts and Connecticut branches, positioning it well to compete with larger banks. It will also have lots of excess capital to fund growth.”

Bill Crawford, president and CEO of Rockville, and Jeff Sullivan, COO of United, would agree with all that.

They will become CEO and president, respectively, of the new United, if the merger clears the remaining hurdles, and both believe this merger represents a huge step forward for both institutions and an opportunity to do something together that they certainly couldn’t do apart — at least not for a long time.

“We’ll have great strategic options,” said Crawford, noting that the entity created by the merger will have $150 million in excess capital that can be deployed in a number of ways. “We’ll have the ability to grow organically and later look at partnering with other banks through acquisition. Each bank, independently, could have grown, and would have done reasonably well, but how long would it have taken Rockville, with $2.2 billion in assets, to get to $5 billion? This deal puts us ahead six or seven years, and it’s the same for United.”

“We’ll have great strategic options,” said Crawford, noting that the entity created by the merger will have $150 million in excess capital that can be deployed in a number of ways. “We’ll have the ability to grow organically and later look at partnering with other banks through acquisition. Each bank, independently, could have grown, and would have done reasonably well, but how long would it have taken Rockville, with $2.2 billion in assets, to get to $5 billion? This deal puts us ahead six or seven years, and it’s the same for United.”

But while MOEs bring many potential benefits to the parties involved, they are in many ways more complicated than traditional acquisitions, where the acquiring firm sets the tone, takes the name, and dictates most of the terms.

“What’s challenging for us — and really interesting for us — is that this is a merger, not an acquisition,” Sullivan explained. “We have to reinvent almost every business process we have at the bank. In an acquisition, the acquiring bank says, ‘welcome to the family, this is how we do things, get on board.’ We’re building a new company in a lot of ways by taking the best practices of both banks, or, in some cases, saying, ‘neither one of us is an all-star at this — and we need to think about a different way of doing business.’

“So we’re spending a lot of time in the weeds looking at all business processes and all of our technology,” he went on, “and looking at how to do things better. If this were an acquisition, it would be a lot easier.”

While hammering out these details, officials with both banks, but especially those at Rockville — who use the marketing slogan ‘Rockville Bank … That’s My Bank’ and whose customers will experience a name change — are explaining that little, if anything, else will be different when this new institution makes its debut.

“The United name stands for the same things the Rockville name stands for,” Crawford noted. “That’s what I’ve told the Rockville customers — we’re merging with someone who’s very similar to us; the main differences are they’re in a different state, and their logo is green. That’s where the differences end.”

By All Accounts

Crawford and Sullivan both acknowledged that, until fairly recently, it would be hard to imagine putting the number $5 billion and the phrase ‘community bank’ together in the same sentence.

But the times — and the numbers — are changing.

Indeed, when Bank of America and Wells Fargo have more than $2 trillion in assets and many institutions have several hundred billion, $5 billion represents a “rounding error” for such banks, said Crawford. Meanwhile, he added, given current trends and challenges, community banks need to be far more concerned about being too small than what some might perceive as too big to be worthy of that designation.

“It’s very difficult to do what you need to do from a risk-management-compliance perspective, and in terms of technology investments to serve your customers,” he explained. “That’s why you’re seeing these mergers of equals across the country.”

Richard Collins, president and CEO of United, who will retire when the merger deal closes, agreed. “Increased scale is important in a number of ways,” he said. “It’s getting harder to go a good job these days; the regulatory thrusts are omnipresent, and having the funds available to get the technology you want to keep up with what’s happening today is critical, and that means getting bigger is important.”

And United has been getting bigger in recent years, expanding its footprint through two significant mergers. The first came in 2009, when the bank acquired Worcester-based Commonwealth National Bank, taking the United name east, almost to Route 495. And in 2012, United acquired Enfield-based New England Bancshares, bringing the brand as far south as New Haven County.

As it eyed further expansion, United focused its attention on Rockville, as well as the trend toward MOEs, which, analysts say, have enormous potential for the stakeholders, but also come with a high degree of difficulty when it comes to putting the deal together.

There have been several MOEs in recent months, including the pairing of SCBT Financial and First Financial Holdings in South Carolina, Home BancShares and Liberty Bancshares in Arkansas, Heritage Financial and Washington Banking in Washington State, and Provident New York Bancorp and Sterling Bancorp in New York.

It was the proximity of that last merger, not to mention the positive response from investors, that caught and held the attention of those at United and Rockville, who by that time were in serious discussions about a deal of their own.

“This was a strategic merger of equals, and when we saw how investors responded and how that deal was put together, it was very instructive of what we could do that would make a lot of sense for both banks and their customers,” Crawford noted. “What was interesting about that deal is that they announced it, and both stocks went up, which almost never happens in any kind of acquisition or merger; usually one goes up and one goes down.”

Richard Collins, president and CEO of United Bank, who will retire when the merger is finalized, says there are many advantages to being bigger in today’s banking climate.

Collins told BusinessWest that the banks, similar in size and other characteristics, have had mostly informal talks about a merger for several years, but moving forward wasn’t possible until Crawford, who took the helm at Rockville in early 2011, completed the process of converting the institution from a mutual bank to a stock institution.

“United was growing very nicely and had just done an acquisition, and we were growing organically, and we just sort of hit this intersection point,” said Crawford, adding that, when the merger deal involving the banks was announced in November, both stocks went up.

United in Their Vision

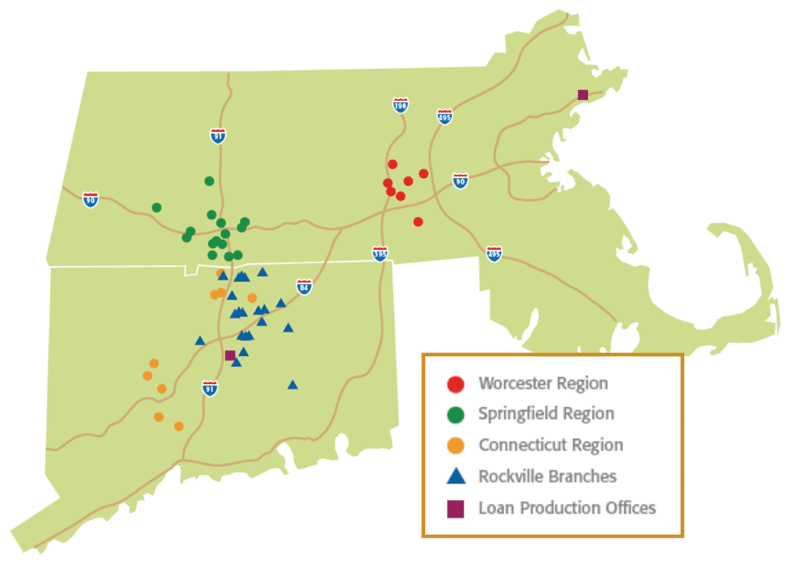

The ‘new United’ will include 55 branches, 18 in Western Mass. (what would be considered the original United footprint) as well as seven in the Worcester area added through United’s acquisition of Commonwealth National, nine in Connecticut added through the merger with New England Bancshares, and 21 Rockville branches. There are also two loan-production offices.

The branches in Western Mass. and Connecticut are clustered along the I-91 corridor, said Sullivan, adding that the Rockville branches essentially fill in a gap between United locations in the northern and southern areas of the Nutmeg State. The new footprint (see map, page 17) closely approximates what economic-development leaders in both states call the Knowledge Corridor.

And this is a very attractive, stable market, said Crawford, one with strong potential.

“While these markets don’t grow rapidly, they are dense, they have high population, and they’re relatively high-income markets compared to a lot of the United States. These are good markets to be in, and ones where we can take share from the large banks; that’s how we grow both companies.”

There was considerable give and take in the negotiations between the two institutions, said Crawford, which involved everything from where the bank would be headquartered to what it would be called.

With the former, the decision was made to base the bank in Glastonbury, although there will be an operations center in West Springfield, and Crawford, Sullivan, and other officials will have offices in both states. As for the name, it was decided that United would travel better than Rockville, which is associated with a community and region, while United has no geographic reference point.

“The Rockville name has been there since 1958, and the Rockville directors, employees, and customers have a lot of pride in that name,” said Crawford. “But at the end of the day, when you think about which name will travel better, United made the most sense; if they were the Bank of Springfield and we were United, I think United still prevails.”

Moving forward, while there is still considerable work to do with integrating the banks, Sullivan and Crawford said, the ultimately bigger challenge will be to take full advantage of the opportunities that come with the scale this merger creates.

“It’s easier to say bigger is better,” said Sullivan. “The challenge is proving it.”

Elaborating, he said the merger positions the new United effectively — it will be exponentially smaller and far more nimble than the large regional and national banks, such as BOA, but also considerably larger than most of the community banks in that Hartford-Springfield market. This size should enable the emerging bank to be both high-tech and high-touch at the same time, and with a large lending capacity. All that amounts to a rare and enviable combination that has certainly caught the attention of the industry.

In addition, the merger will generate economies of scale and efficiencies — the deal is expected to generate approximately $17.6 million in fully phased-in cost savings (15% of the expected combined total) that should enable it to better navigate the turbulent conditions in which banks currently operate.

“This merger will give us the ability to better deal with the costs of operating a business in our industry right now,” said Sullivan. “The compliance costs, the regulatory stuff that’s going on, are changing the game at a very rapid rate.”

The Bottom Line

Time will tell if the ‘new United’ can take full advantage of the opportunities created by scale and become the powerhouse that some analysts are predicting.

But for now, the future certainly seems bright for two banks that were doing fine on their own, but are expected to do much better through this merger of equals.

“As we put the companies together, we’re trying to think about how we not just get incrementally better,” said Sullivan in summation, “but whether we can leapfrog two or three steps in our development as individual companies and come out with something better than the sum of its parts.”

Right now, that sounds like something this new entity can bank on.

George O’Brien can be reached at [email protected]