Springfield Diocese Looks to Create Momentum for Catholic Education

Paul Gagliarducci says it’s likely ground won’t be broken for the new Pope Francis High School — the institution resulting from the merger of Springfield Cathedral and Holyoke Catholic High Schools — until September 2016.

While the location for the school (the site of the old Cathedral, destroyed by the 2011 tornado) has been chosen — after months of weighing various options — as has the name and nickname (Cardinals), and a working architect’s rendering of the facility has been circulated, much work remains to be done before a shovel can be put on the ground, he noted.

Indeed, administrators must decide how many classrooms to include, the nature and size of those facilities, and myriad other specifics before architects can begin, let alone finalize, designs, said Gagliarducci.

And from the big picture perspective, administrators involved in this endeavor have much more to do than construct a new school, he went on. They are also building enthusiasm — and a student body — for this facility, while also ensuring its long-term sustainability.

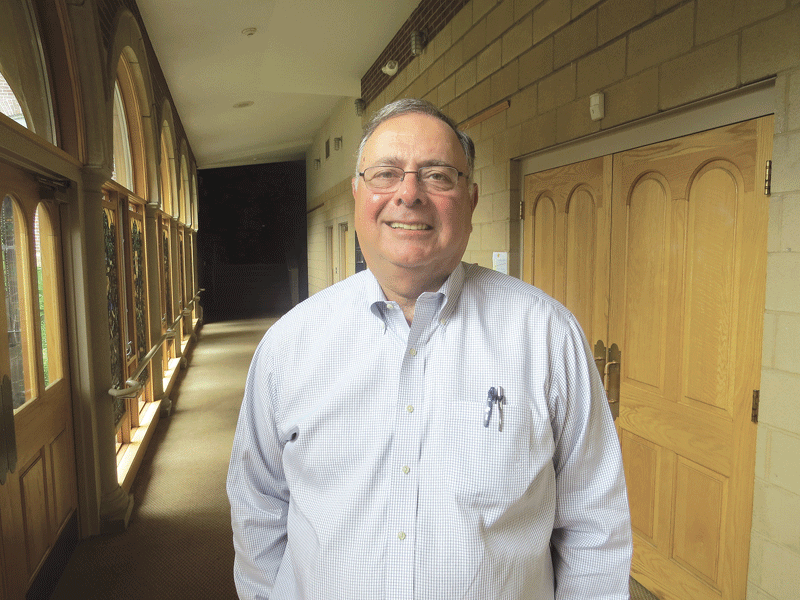

And all this is reflected in the unofficial title Gagliarducci, former school superintendent for the Minnechaug region and Somers, Conn., and long-time education consultant, now carries with regard to this endeavor.

That would be ‘interim executive director of the Pope Francis High School project,’ an assignment of indeterminate length — “I’m here as long as it takes to get the job done” — that will involve everything from coordinating the merger of the two schools to building the new facility, to designing a new governing structure for the diocese, all at a time when there are huge question marks hanging over the institution of Catholic education in this region and around the country.

Those question marks are reflected in statistics kept by the National Catholic Educational Assoc. (NCEA), based in Arlington, Va. They show that enrollment is not only down considerably from the peak years for Catholic education in the early ’60s, when there were 5.2 million students enrolled in 13,000 schools across the nation, but that the decline is an ongoing phenomenon, with no apparent bottom in sight.

Paul Gagliarducci says the unofficial goal for Pope Francis High School is to make it one of the few Catholic facilities that has a waiting list for students wishing to enroll.

There are many reasons for this decline, said Sr. Dale McDonald, PBVM, Ph.D., director of Public Policy and Education Research for the NCEA, who cited everything from the recession that came near the middle of this statistical period, to a sharp drop in the number of priests and nuns who once taught in Catholic schools, to the financial woes facing a number of dioceses across the country.

Overall, though, sharply falling enrollment comes down to a continuing decline in the number of people both willing and able to pay the tuition ($9,000 on average nationwide at the high school level, and $3,800 at the elementary school level) for a Catholic education.

Over the past decade, decline in enrollment has averaged between 1.8% and 2.5% per year, and 21% of the schools have closed, McDonald went on, and there is little, if anything, to indicate that this trend will slow, let alone stop.

“Unless we have some serious interventions, enrollment will continue to decline and schools will continue to close,” she said, adding that by interventions, she meant actions that would enable more families to afford those tuition figures mentioned earlier.

Cathedral and Holyoke Catholic have certainly not been immune to these trends. At Cathedral, for example, enrollment was at or near 3,000 in the early ’70s, and stood at merely 400 when the tornado tore across Springfield on June 1, 2011.

The current trends and uncertainly concerning the future certainly played a factor in the lengthy discussion about whether to rebuild Cathedral, where, and how — and also in the preliminary design of the school and projected capacity — roughly 500 students.

That’s about 115 more than the combined enrollment of the two high schools at present, said Gagliarducci, adding that this number reflects both realism and confidence moving forward.

“Looking at the group of freshmen coming in, the class of 2019, has just over 100 students, and that’s a pretty good number,” he said, adding that this is the combined enrollment for both schools, “If we can maintain that 100 to 125 students, and I think we can, we’ll have our 400-500 students and something we can build on.” Such confidence, he went on, stems from everything from the impact of a new facility on those weighing their education options, to efforts to emphasize the value and benefits of a Catholic education.

But making the school accessible to families of all income levels will be crucial, and for this issue and its focus on education, BusinessWest looks at that challenge and how it might be met.

Setting a Course

As he talked about his assignment, the Pope Francis High School project, moving forward, Gagliarducci said that while it doesn’t say as much on any formal or informal job description, his mission is to make the new facility one of those Catholic high schools that actually has a waiting list for enrollment.

Doing so will accomplish many things, he went on, listing everything from fiscal flexibility to greater prestige to long-term sustainability.

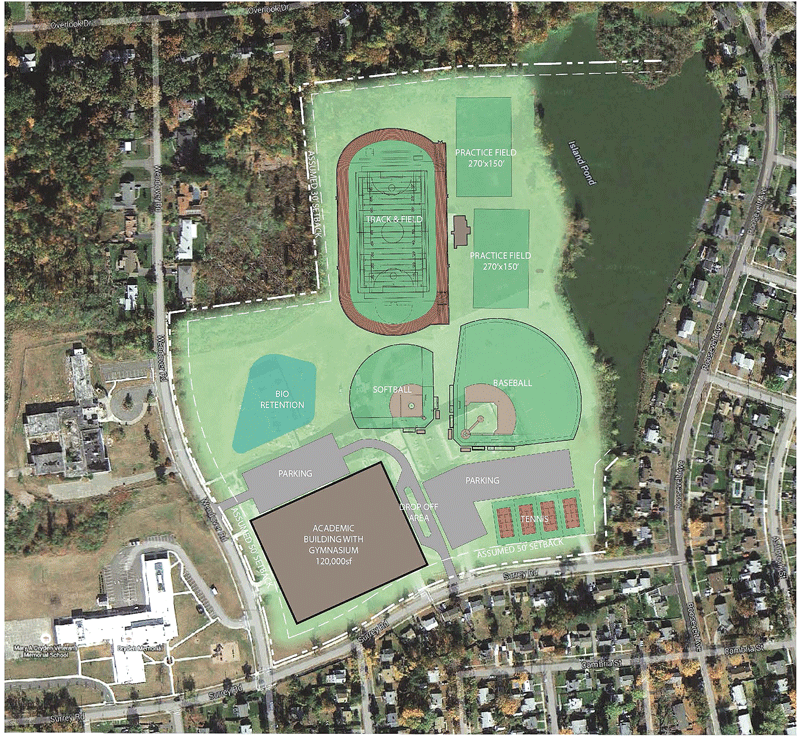

While designs for the new school are still being finalized, the plan for the property on Surrey Road is coming into focus.

Such an eventuality would have seemed impossible a few years ago, especially after Cathedral was relocated into a shuttered elementary school in Wilbraham months after the tornado — and this scenario still seems like a real stretch of the imagination to many.

But Gagliarducci and others involved with this endeavor believe such a fate is possible, if the school can focus on those two parts of the enrollment equation mentioned earlier, and put more people in those categories of individuals willing and able to pursue a Catholic education for their children.

Essentially, it will come down to the laws of supply and demand, and reversing the picture that has defined the scene both regionally and nationally for years — where demand doesn’t come close to approaching supply.

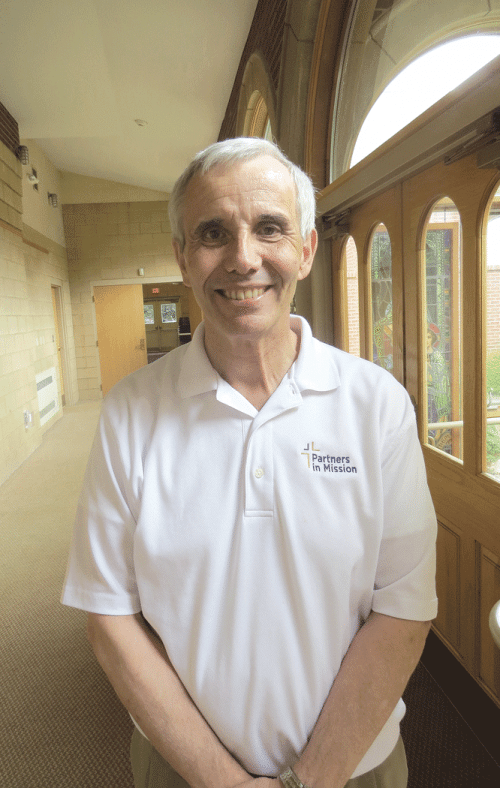

And that assignment will come down to a host of factors, said Tom Brodnicki, senior partner with Partners in Mission, a consulting firm specializing in Catholic education that has been hired by the diocese to help coordinate the merger of the high schools and raise money for the endowment fund.

He listed listing everything from building a market for Catholic education to growing the endowment so more students can attend; from broadening enrollment among certain demographic groups, such as the Hispanic population (more on that later), to convincing area parents that the sticker price for Pope Francis is a relative bargain; from building what he and others called a “culture of philanthropy” in the region, to convincing parents of the need to start saving early for a Catholic education for their children.

All of those action items would fall into that category of ‘interventions,’ as described by McDonald. The question is whether they will be enough to stem the current tide.

Indeed, creating a waiting list for Pope Francis will certainly be a challenge, said those we spoke with, noting that while there are, in fact, schools where demand exceeds supply (often where the supply has been reduced through a merger), there are many more that are closing their doors or merging with others, as has happened with the Springfield diocese.

Statistics from the NCEA show that while 27 new Catholic schools opened over this past school year, 88 consolidated or closed. And those numbers have become the trend over the past few decades, said McDonald, adding that the rate of closure and consolidation has actually slowed considerably because there are simply fewer schools left to take such steps.

And while the economy and even demographic trends have had something to do with these developments — the decline of many cities in the Rust Belt/Bible Belt has resulted in falling Catholic school enrollments in that traditional stronghold — tuition, the inability to meet it, and the fiscal difficulties that ensue, are the primary reasons.

“As tuition moves higher, fewer people are able to afford it,” McDonald noted. “But schools facing lower enrollment still have expenditures, or operating costs, and many of these costs are fixed or increasing dramatically, such as health insurance for teachers and staff.”

Per-pupil costs generally far exceed tuition and are met through fund-raising efforts by the diocese in question, she went on, adding that there is help available to families facing those tuitions costs ranging from scholarships to tax credits made available in many states.

But the burden is proving too steep for many, especially those families with several children in school at the same time, McDonald noted, adding that, overall, there is little prospect for improvement.

“Without programs that will provide help for families, it’s not a happy forecast in many respects,” she said, “when it comes to the ability of parents to continue to pay the tuition that’s required to have a quality education.”

One of the serious, and ongoing, challenges for those in Catholic education is attracting members of the Hispanic population, said Patricia Weitzel-O’Neill, president of the Barbara and Patrick Roche Center for Catholic Education at Boston College.

Hispanic populations are growing in most urban centers, including Springfield and Holyoke, and, overall, Hispanics comprise roughly 60% of the nation’s Catholic-school-age children (those ages 3 to 18), but only 2.3% of those children are enrolled in Catholic schools.

“This is the crux of the problem in Catholic education today,” she told BusinessWest, adding that there are several reasons behind that statistic, including the fact that many Hispanic parents did not attend Catholic schools, and doing so is not a “part of their culture.” But the inability to meet tuition costs is also a huge factor.

“One of the issues facing Catholic education today is the inability to recognize the need to diversify what we’re doing, to be much more welcoming, and to be more open to introducing and welcoming the second culture and the second language,” she said, adding that there is movement nationally to address the problem.

Crosses to Bear

It was in this environment that the Springfield diocese was forced to make critical decisions after Cathedral was essentially destroyed by the tornado.

And it took all of four years to make most of those decisions, including whether to rebuild, under what circumstances (eventually via a merger with Holyoke Catholic), where to build, and how big to build.

After surveying the landscape and analyzing the data, officials decided to build a 120,000-square-foot school that can handle a population of 500 students. That is a small fraction of the total number of Catholic high school students in this region from a typical year decades ago — and a figure smaller than many alums of those schools think is possible — but it is quite realistic, said Gagliarducci.

“Some people think we should be doing much better — some of the critics said earlier that this area should be able to support four high schools,” he said. “Dream on … that’s just not going to happen.”

But Gagliarducci stressed that the facility can, and hopefully will, be expanded to accommodate more students in the future.

Facilities such as the auditorium, gymnasium, and cafeteria are being designed for closer to 700 students, he went on, adding that they cannot be expanded later, and thus must be built accordingly. But additional classrooms and facilities can be added later.

Tom Brodnicki says that one challenge for the diocese is to convince parents that their tuitions costs are a sound investment.

By building a first-class facility — not only a new building, but one outfitted with the latest technology and offering attractive programs of study — they hope to build demand. And it will take more than a new structure, because several area communities, including Longmeadow, West Springfield, Wilbraham (Minnechaug), and Chicopee (two facilities) have opened new state-of-the-art high schools in the past decade.

“The key is to develop a program that parents can get excited about,” Gagliarducci explained. “But ultimately, if I’m deciding as a parent to send my child to Pope Francis High School, I’m doing so because I believe in a strong religious education for my kids, so that has to be the paramount thing that’s going to attract people.

“But then you have to follow that up with a rich academic program,” he went on, “one where, at the end of four years, students are getting into the college of their choice; that’s very important.”

By growing an endowment, meanwhile, they intend to increase accessibility. Also, with economies of scale gained through the merger, they expect Pope Francis to be an efficient operation, one better suited to manage through the time it will take to build the endowment and grow enrollment.

“We believe that with the new facility and some of the excitement that it builds — along with this endowment fund, which will help with the affordability factor for some families — that a school with a projected enrollment of 500 is within reason,” said Brodnicki. “The real key is the level of academic excellence that’s provided, and convincing people that they are making a valuable investment in their children’s future.”

Elaborating, Brodnicki and Gagliarducci said Catholic education has not gone out of favor — it has simply become a less-appealing option for many families due to its cost.

The initial goal for the endowment, set by Bishop Timothy McDonnell, who retired last year, was $10 million. But Gagliarducci and Brodnicki want to set the bar higher to broaden accessibility and therefore meet demand.

Approximately one third of the 200 students now attending Cathedral receive a substantial amount of financial assistance to attend, said Brodnicki, adding that a large endowment and other forms of philanthropy will enable more low-income families to attend the school.

But to achieve sustainability, the new school must be able to attract students across all income levels, said Gagliarducci, adding that the goal is to continue the current breakdown — where roughly one third of the students pay full tuition, another third get some support, and the rest get substantial assistance — only with a larger student population.

Building Momentum

Surveying the national Catholic education scene, Brodnicki, who has had a front row seat to the changing landscape and has worked in a number of major metropolitan areas, said most cities are experiencing declines consistent with the statistics quoted by McDonald.

The Boston area is a notable exception, he added quickly, noting that most Catholic schools there are thriving, in part because the economy is more robust, but more so because of strong philanthropic support from wealthy individuals, many of whom are graduates of those schools and now serve on their boards of trustees.

“A few things happened in Boston,” said Brodnicki. “First, the economy took off; second, there is incredible wealth and a strong tradition of philanthropy. There are a number of Catholic individuals who have come together and made a firm commitment to Catholic education, especially the inner-city schools.”

The Western Mass. Catholic community can’t expect to approach that level of support, he went on, but it can — and, in essence, must — build a stronger base of philanthropic generosity if it hopes to create a sustainable Catholic education system.

And he said Cathedral, and to a lesser extent Holyoke Catholic, has a large alumni base, with many individuals in a position to provide support. The diocese must be more aggressive in reaching out to alums and making its case for support, he went on.

“Cathedral has a reputation for having many well-known graduates who have achieved wealth,” Brodnicki explained. “We’re going to go and visit those folks and lay out the case for support.”

While building a stronger base of support through its endowment and other forms of philanthropy, the Springfield diocese must also more aggressively promote Catholic education and convince current young parents, as well as those that will follow them, that it is a viable option and worthwhile investment.

Part of this equation involves making Catholic education more of a K-12 phenomenon, said those we spoke with, who again cited the more-rapid rate of enrollment decline at the elementary school level.

Springfield is a good example of that trend; not long ago there were five Catholic elementary schools in the city, but by the time the tornado touched down, they had been merged into one — St. Michael’s Academy.

Meanwhile, the diocese, as it goes about selling the new high school, must also sell a Catholic education, and this one in particular, as an investment, rather than as an expense that must somehow be met.

“People often view that $9,000 as tuition, not necessarily as an investment, Brodnicki explained. “We have to show someone who’s looking at spending $40,000 on their child’s education that, on average, graduates of Cathedral and Holyoke Catholic are receiving scholarship opportunities that average in the $80,000 to $90,000 range; people have essentially doubled their money in four years. Give me a stock that will do that, and I’m all over it.”

Grade Expectations

How well Gagliarducci, Brodnicki, and the diocese fare with the many aspects of the Pope Francis High School project remains to be seen. With some elements of the equation, such as the endowment, real progress may not be realized for years.

One thing that all agree on, though, is that given the many changes and challenges confronting those in Catholic education today, this will certainly be a stern test.

Ultimately, though, they believe this is a test they can, and will, pass.

George O’Brien can be reached at [email protected]