Team Work

A Textbook Example of Effective Job Sharing

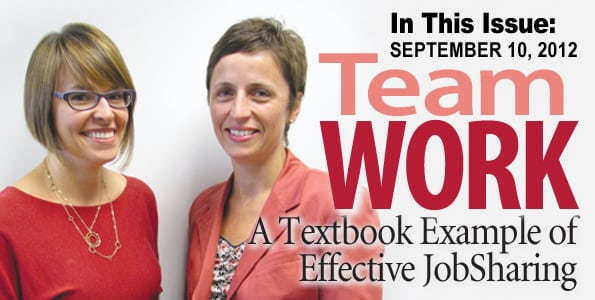

While job sharing is hardly a new concept — it’s at least a few decades old by most accounts — it has rarely succeeded, or even been tried, at a high-level administrative post, such as vice president of Philanthropic Services at the Community Foundation of Western Massachusetts, which is now being shared by Kristin Leutz and Katie Allan Zobel. For one of them (Leutz), this is a chance to live out research she did while attaining a master’s degree in Industrial/Organizational Psychology at Springfield College. For both, it’s a way to achieve coveted work/life balance while also carrying out highly rewarding work. What they’ve been doing for the past seven years can be described with one word: pioneering.

While job sharing is hardly a new concept — it’s at least a few decades old by most accounts — it has rarely succeeded, or even been tried, at a high-level administrative post, such as vice president of Philanthropic Services at the Community Foundation of Western Massachusetts, which is now being shared by Kristin Leutz and Katie Allan Zobel. For one of them (Leutz), this is a chance to live out research she did while attaining a master’s degree in Industrial/Organizational Psychology at Springfield College. For both, it’s a way to achieve coveted work/life balance while also carrying out highly rewarding work. What they’ve been doing for the past seven years can be described with one word: pioneering.

There’s a small pile of rocks — one of the owners actually called it a “sculpture” — sitting in the middle of the table, or leaf, that lies between the desks occupied by Katie Allan Zobel and Kristin Leutz.

These items come in all sizes and shapes (including a few that look like hearts — Leutz collects and treasures those), and they were brought back to Springfield from many different travel destinations. Most are gifts from one to the other, but some were found and simply added to the mix.

Kristin Leutz says the unique job-sharing situation she entered allows her to live out the research she did at Springfield College and MassMutual.

That starts with a job — vice president of Philanthropic Services for the Community Foundation of Western Massachusetts — and its salary and needed benefits. They also share an office, a copier, that leaf with the rocks, a bookcase that is far too cluttered for either one’s good, the nameplate outside the door, and even the door itself (items chosen by both, ranging from newspaper cartoons to art created by Leutz’s youngest child, now compete for space).

It’s been this way since the late fall of 2005, when Zobel and Leutz applied as a team for a position then called director of Development, and prevailed over several traditional hopefuls — meaning singular men and women — in a decidedly different candidate-selection process (more on that later).

Currently, Leutz works Mondays and Tuesdays, Zobel takes over on Thursdays and Fridays, and they’re both in on Wednesday, or what has come to be known, alternately, as ‘overlap day,’ ‘hand-off day,’ and ‘pass-the-baton day.’

Between them, they have raised between $5 million and $8 million per year, said Kent Faerber, former president of the foundation and now interim president, and been highly successful in a multi-faceted position that has involved everything from fund-development management to PR and marketing, to promoting philanthropy across the region.

“This has been a very challenging job to share because of the sophistication of the work and the need for our external constituency to feel that their relationships with the foundation are seamless,” he told BusinessWest. “While a prospective donor might make initial contact with one of them, the other needed to be able to pick that up whenever he or she might call back or make contact later. They have developed quite extensive routines of information sharing and collaboration despite the fact that they are normally not in the office or on duty at the same time.”

When asked how they are able to succeed in this unique and challenging sharing arrangement, Leutz and Zobel used different words and phrases to say what amounts to the same thing: they work hard at it. And they need to, because, while having two minds working on all that goes into this job description is certainly beneficial for the foundation, such a scenario can get complicated.

“To try to figure this out is not simple; it’s not a straightforward thing,” Zobel said of job sharing in general. “We’re true pioneers.”

That’s a word that both used early and often, because there is very little job sharing going on in this region in general, and only a few examples from across the country of it working at such a high administrative level. The two are well-aware of this, and understand that their partnership could be considered ground-breaking and a potential model.

For this issue and its focus on women in business, we take a look at this unique employment arrangement, how it came about, and why, seven years later, it’s stronger than ever.

Sharing the Wealth

Carol Leary, president of Bay Path College and a long-time (now former) board member and president of the Community Foundation, remembers the search that eventually brought Leutz and Zobel to the organization — as well as her reaction to a situation (a teamed pair of candidates) that she hadn’t seen before and hasn’t seen since, at least at that level.

“I really didn’t have to be convinced very much — I loved the concept of trying it,” she recalled. “My sense was that the worst thing that could happen was that it wasn’t going to work … and I figured it was well-worth the risk because we didn’t want to lose either one of them.”

But Faerber, president of the foundation at the time, remembers that there was considerable skepticism among other members of the search panel, especially about the logistical aspects of such an arrangement. What eventually swayed them, he believes, was the prospect of putting two strong, creative minds to work on the many challenges and opportunities that would confront whomever held that title.

Katie Allan Zobel says she wanted to work for the Community Foundation, but couldn’t handle a 55-hour week, and the job-sharing arrangement allowed her to advance her career goals.

How these two minds came to sit across the table from those interviewers is an intriguing story, which starts at Amherst College in the mid-’90s, where Leutz and Zobel worked together in the broad realm of fund-raising and alumni relations.

They thrived in those roles, but Leutz eventually left the school to pursue a master’s degree in something called Industrial/Organizational (I/O) Psychology at Springfield College. This is an emerging field, she explained, that involves the scientific study of employees, workplaces, and organizations, and covers many aspects of human resources and organizational development, including a wide range of work/life balance issues and trends.

These specific areas of study defined her master’s thesis work at MassMutual. “I was looking at what they called alternative work arrangements there,” she explained, adding that job sharing was part of the mix, but there was a very limited study pool. “I did a large-sample survey and qualitative study of their employees and what kinds of work/life arrangements they were using — alternative schedules, part-time work, and other initiatives.”

She would eventually go on to work for the company as an organizational-development consultant in the Human Resources department, working on what amounted to the human side of a large-scale implementation of the SAP technology system. Little did she know that soon she would be taking much of what she learned in the classroom and at the financial-services giant and applying it to what amounts to a pioneering experiment.

Fast-forwarding somewhat, Faerber reached out to Zobel in the early fall of 2005 when she was an independent consultant (Amherst College was one of her clients) and asked if she could provide temporary support for the Community Foundation when its director of development was stricken with the cancer that would eventually take her life, and was then on leave of absence.

Zobel recalls being somewhat reluctant at first, but agreed, and soon found the work rewarding and the foundation an organization she enjoyed working for. “I was here for three months, and came to realize what an amazing resource the Community Foundation is. I had no idea the extent of their work and the way in which they did that work; it was both surprising and so engaging that I wanted to stay and apply for that position.”

But she determined fairly quickly that the 55-hour work week that the job entailed was something she didn’t want at that time in her life, with two young children.

Zobel recalls initial discussions with Leutz (who by this time had left MassMutual after the birth of her first child, ironically because she couldn’t work out the flex-time arrangement she desired) about the possibility of sharing this job. She did so without knowing the full extent and specific direction of Leutz’s graduate work — “I knew it was organizational development, but not much more than that” — and found her very open to what at that time amounted to exploring uncharted territory.

“This was a chance to live out my research and test it out,” Leutz recalled. “I was working way too many hours at MassMutual after the birth of my son, and didn’t have the work/life balance that I wanted. Here was the work/life expert having no balance; it was like the shoemaker’s children having no shoes. I was home with my son and ready to work, but not full-time.”

“When Katie came to me with this opportunity, which represented a chance to work in philanthropy in a way that I hadn’t before, I was excited,” she continued, “and I knew how to structure the job. So we applied for the position as a team.”

Work in Progress

Since getting the job and putting both their names on the plate outside their office, Leutz and Zobel have had an additional — and unique — segment attached to an already-lengthy job description: making their employment arrangement work for all parties involved.

This assignment involves everything from financial considerations, or costs to the organization, to ensuring seamless (that’s another word both women used repeatedly) delivery of services to the many kinds of clients who work with the Community Foundation.

As for the financial side of things, if two people are going to take a job that would normally be carried out by one individual, they theoretically can’t cost more than that one person would if things are going to work out for the company. And for the most part, that’s been the case with Leutz and Zobel.

Neither one has needed health insurance through the organization, which helps — if both did, that would be an additional expense — and their salary and other benefits amount to no more than what one individual would earn. There are some additional expenses — two computers and two phones are required, and if they travel together on conferences, there are two plane tickets and two registration fees (they split a hotel room) — but not many.

As for achieving a seamless operating environment, this involves constant and highly effective communication and making the very most of those aforementioned hand-off days.

Backing up a bit, the co-vice presidents went into some detail about what the foundation does and what their responsibilities are.

The foundation itself administers a charitable endowment consisting of approximately 528 separately identified funds (totaling $110 million) serving Hampden, Hampshire, and Franklin counties. The foundation also plays a central role in the charitable distributions from four large private foundations in the region, administered by Bank of America and representing approximately $24.6 million in additional charitable assets.

As for Leutz and Zobel, their official job description reads this way: “manage fund development and donor services; provide charitable gift-planning services to individuals, families, and groups, including planned gifts and gifts on non-cash assets; serve as a partner to local professional advisors assisting their clients in charitable giving; promote philanthropy in the region among stakeholders including institutions, individuals, and corporations.”

There are myriad responsibilities that go with that description, said Zobel, adding that, for two people splitting a week to carry them out, there must be communication, organization, and efficient sharing of those most important ingredients: information and opinions.

Elaborating, Zobel said she and Leutz will use Tuesday evening and then their traditional Wednesday carpooling (they both live in Amherst) to stay abreast of what’s happening with their many constituencies and plan a smooth flow of service and teamwork.

“On Tuesday evening, Kristin puts down in an e-mail to me what we call our ‘transition memo,’” she explained. “It explains everything that has happened, with highlights and bullets and an ongoing project list that we continually update; some things come off the project list, while others are added on that we need to do.

“We use that Wednesday commute to talk things over,” she continued. “I’ll have read the memo, looked it over Tuesday, and we’ll talk about those things that really need discussion.”

Said Leutz, “we basically talk on the phone a lot on our off days as well. We try to respect time off, but we wind up talking a lot because it makes things easier. And we use that commute to make the most out of discussing things that need decisions together or relationships that we share equally.”

Checking Your Balance

And while this job-sharing relationship has worked out well for the Community Foundation, it has also been everything Leutz and Zobel could possibly have expected from it — and more.

Indeed, they both talked about how this arrangement has done more than help them achieve work/life balance. It has also enabled them to be in a creative, rewarding job they could not have taken on otherwise, while also putting them in a collaborative environment that has allowed them to stretch their collective imaginations and become even better at what they do.

It’s such an attractive work environment that Leutz has stayed in it far longer than she has any other employment situation.

“I’m a restless person — this is the longest I’ve stuck with anything,” she said. “And I think that’s because I’m a collaborative thinker; even if I was working full-time, I would want to work this way, with people, because it enhances my production.”

Zobel agreed. “To do this kind of work on your own would be much harder. I can get a lot of feedback from Kristin throughout the week and from week to week about what I’m doing right, what I should change … I get infused with new energy.”

The downside to the arrangement, or at least one of them, they said, is that they are now latched to each other career-wise, a fairly tenuous situation, but one that neither one is worried about at the moment. After all, the relationship has survived a parental leave (Leutz had her second child a year after they took the job) and the need for both to earn higher wages, which they’ve accomplished through outside consulting work.

“You have to be much more creative with your own career to stay committed to someone at this level,” said Zobel. “That’s not necessarily a disadvantage, but it’s certainly a challenge.”

When asked if job sharing is a viable option for area companies and individuals working for them, both Leutz and Zobel said they provide ample proof that such arrangements can work.

But both employer and employees have to fully understand the concept, its many potential benefits, and the myriad challenges before they attempt to implement such a practice, they said.

And that starts with individuals fully understanding that, when they split a job, they take half the salary. That sounds simple, but many don’t get that part, said Zobel.

“People get all excited about this idea when we talk about it,” she told BusinessWest. “What Kristin and I wanted was a really meaningful, significant, meaty job, and you don’t usually get that in a part-time job; you either have to work much more than part time, or you work part-time and don’t get everything you want.

“Many of our peers feel the same way,” she went on. “And that’s why they get so excited about this. But then when they realize they only get half the salary, they get these startled looks on their faces.”

Moving beyond that all-important consideration, such arrangements can only work when the two individuals can work together effectively and establish a very high level of trust, something that has been accomplished in this case.

“I know when I’m not here, the work is getting done at as well as I would have done it, if not better,” said Leutz, “because Katie is here and I have complete trust in her.”

In general, job sharing has worked best with positions like administrative assistant, Leutz explained, but it has been effective in a variety of settings and with many different job titles.

“Any job share should be able to be matched to the work and to the role, but there are certain jobs that would be very difficult for people to share, and there are many ways that people structure job shares,” she said. “Some people have very discreet responsibilities and don’t overlap very much, and other people share everything because of the nature of the work.

“There are examples from around the country where executive-level employees, women and men, have been able to do this,” she continued. “But they have tended to structure these arrangements very creatively depending on the organization and the needs of the job. And we figured we had to do that here; we had to really understand the nature of the work and make ourselves flexible.”

Looking back, Leutz and Zobel both noted that they didn’t have all the answers for that search panel back in 2005, and that it’s taken the ensuing seven years to completely fill in their canvas. They’re not sure how long this relationship will go on, but for now they’re more than content to continue their pioneering efforts.

Two the Future

The level of sharing between Leutz and Zobel apparently goes further than the two understood — at least until recently.

Indeed, Leutz has one of those office chairs with a large rubber ball as the seat — chosen for ergonomic reasons (something else she learned while studying I/O Psychology). And when BusinessWest noted that Zobel uses a more traditional model, she admitted to her office mate, “I often use yours when you’re not here,” which was news to Leutz.

But beyond the chair, the door, the copier, and the four weeks of vacation, the two share something else — a firm desire to make this situation work both for them and the organization. It’s been something they’ve certainly had to work at, and it is that commitment to not merely a job, but also a truly unique work arrangement, that has made it successful.

You might say it’s a working situation that’s rock solid — and in more ways than one.

George O’Brien can be reached at [email protected]