Tracking Progress

Union Station Project Moves to Critical Next Phase

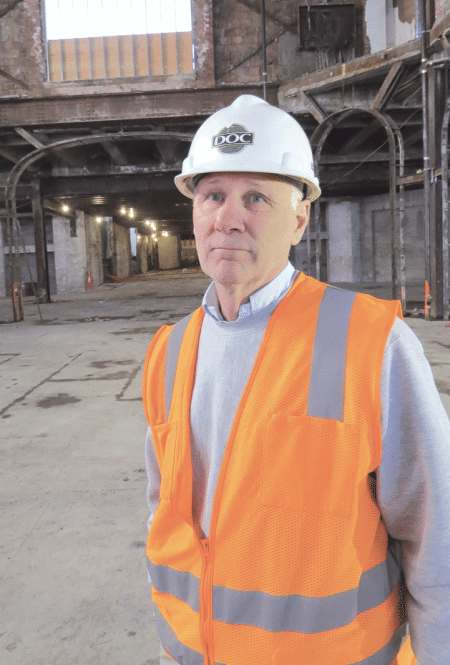

Bob Aquadro stands inside the gutted central concourse at Union Station. Inset: an architect’s rendering of the planned new concourse.

He had become quite familiar with the dark, dank interior of the old station, which has sat vacant and unused for more than 35 years, and many of its features, such as the terrazzo floor, some relics from the golden age of rail, the central concourse, and the famous clock stationed at its south end, its hands seemingly frozen in time.

So the mayor was somewhat taken aback when he walked in the 89-year-old building earlier this month as BusinessWest was offered a tour and update on the ongoing construction there.

He barely recognized the place, and for good reason.

The interior had been gutted right down to the brick walls and the structural steel support beams. The skeletal steel frame of the concourse, with its various-sized arches, was all that was left of the once-proud centerpiece. The clock was gone, and the tunnel that connected the terminal with Lyman Street and the rail platforms above was open for the first time in what is believed to be three decades. The mezzanine and third floors, also gutted to the walls, were inaccessible because the stairways to them had been torn down.

“Wow … this is really opened up,” said Sarno as he walked in the front entrance with Kevin Kennedy, the city’s chief development officer. “This place is huge.”

The work to gut the interior, revealing just how massive the landmark on Frank B. Murray Way is, represents some of the still-early-stage work in a massive, long-awaited, $76 million project to convert the long-dormant station into an intermodal transportation center and, hopefully, revitalize the area surrounding Springfield’s famous Arch. For Sarno and Kennedy, this is a multi-faceted economic-development initiative, one designed to restore a landmark but also create momentum and spur additional activity.

But for Bob Aquadro, senior project manager with Holyoke-based Daniel O’Connell’s Sons, it’s merely the latest — and also one of the largest, most challenging, and most complex — projects in a long career in construction.

Indeed, this multi-phase endeavor entails both new construction — especially a six-level parking garage and adjacent bus terminal — and historic renovation of both the station’s interior and exterior. Meanwhile, it also involves a host of constituencies, especially the two railroads — Amtrak and CSXT — that own the rails above the station and run several trains over them each day at speeds sometimes exceeding 40 miles per hour.

This project also features some rather tight deadlines and extremely difficult work — with both of those elements in evidence with efforts to waterproof that aforementioned tunnel area, one of the next steps in this intricate process.

“This is one of the most complex processes that I have seen in many years — there are a lot of players, and there’s a lot to put together to make this come off properly,” Aquadro said, referring to the tunnel work specifically, but also the project as a whole. “And once we get the railroads on board, we have a detailed phase-in plan for going through their yard and digging up that tunnel.”

There will be many other challenges involved with this endeavor, and for this issue and its focus on construction, BusinessWest looks at how, collectively, they will make this project as intriguing as it is historic.

At top, Union Station not long after it opened in 1926. Above, an architect’s rendering of the renovated station, bus depot, and parking garage.

Platform Issues

Union Station wouldn’t be the first Springfield landmark that Daniel O’Connell’s Sons has constructed — or reconstructed, as the case may be.

Indeed, the company handled the massive rehabilitation of the of the Memorial Bridge in the early ’90s, and it also handled the $60 million initiative to build a new federal courthouse on State Street, a three-year project that was completed in 2008.

Aquadro served as project manager for the federal courthouse work, as he did for construction of the new, $80 million Taunton Trial Court, his most recent major assignment, and another endeavor that stretched through three building seasons.

“Projects I tend to get involved with are generally very lengthy,” said Aquadro with a laugh, adding that work to revitalize Union Station and build its related components will certainly continue that trend. By the time a ceremonial ribbon is cut in 2017, he will have spent close to four years on this assignment.

As he talked about the project, he and Clerk of the Works Leroy Clink stressed that there are many moving parts and a number of intriguing elements — starting with the station itself.

It is coming up on its 90th birthday, said Aquadro, and it is certainly showing its age — not to mention the fact that it has spent more than half its lifetime is serious decline or complete dormancy.

Indeed, like most all of the grand rail facilities, many of them called Union Station, built in the first two decades of the 20th century — many conceived to replace earlier structures that ushered in the era of rail travel — Springfield’s landmark fell victim to the rise of air travel and the nation’s interstate highway system, both of which began altering the landscape in the 1950s.

Changes in how Americans got from one place to another eventually led to the destruction of many of those stations, including, famously (or infamously as the case may be), New York’s Pennsylvania Station, torn down in the early ’60s. Others fell into serious decline and were eventually revitalized and often repurposed. That list includes Washington D.C.’s Union Station, New York’s Grand Central Terminal, Boston’s North Station, Worcester’s Union Station, and many others.

Springfield’s Union Station had to wait much longer than those facilities, but perseverance, especially on the part of U.S. Rep. Richard Neal and Kennedy, who once served as Neal’s senior aide, finally paid off.

Plans to convert the station into an intermodal transit center and mixed-use facility, which have been on the drawing board for more than 20 years, are finally becoming reality, although most of those mixed uses proposed over the years — everything from an IMAX theater to a day-care facility to various forms of retail — have been shelved or scrapped altogether.

What survived were plans to restore the station to something approaching its former glory — at least in terms of aesthetics — and outfit it to accommodate expanded rail service within the region, and also build a new facility that would handle intercity, and perhaps intracity, bus travel.

Work at the station has actually been underway for well over a year now, with much of it focused on asbestos removal — an intricate and time-consuming effort — and then demolition of the station’s former baggage area to make way for the new bus facilities.

Given the station’s advanced age and decades of dormancy, crews spent considerable time assessing its condition and looking for possible surprises, said Aquadro, adding that designers and engineers needed to know what they were up against moving forward.

“That’s one of the reasons we did all this work early, to help the designers see what’s here, because it is very difficult,” he told BusinessWest. “We had to remove a lot of asbestos, and just removing the roof gave us an awful lot of information. There were some surprises, but it goes along with the investigation; this structure was built under different building standards than what we use today, and all of that had to be looked at.”

Dry Subject Matter

Until recently, most of the work at Union Station was conducted out of the public’s view, with asbestos removal and other steps inside the terminal, said Aquadro, adding that the physical landscape started changing with the demolition of the baggage building, which is not complete.

And it will continue to change in a number of ways over the next several months with the start of construction of the parking garage, the bus depot, and a new road that will connect Frank B. Murray Way with Liberty Street.

Still, much of the work will go on behind the scenes, said Clink, including the upcoming work to waterproof the tunnel area and safeguard the complex from rain water.

“The waterproofing that the original builders put on this facility has failed; for this to become a working train station, that water has to be stopped,” he explained, adding that decades ago there were efforts to restore the tunnel without dealing with the water problems, and they met with disastrous results.

“This passenger tunnel is such a challenging piece because there are so many parties involved,” he went on, listing Amtrak, CSXT, and the Mass. Department of Transportation as just a few.

Dealing with these parties has been time-consuming, frustrating, and, yes, expensive, he added, noting that rail officials charge the city (and therefore those budgeting this project) for the time and effort negotiating how the trains will continue running throughout this process.

But all that has occurred to date will likely be a relative walk in the park compared with what’s to come, said Clink, adding that the waterproofing work on the track level must be carefully orchestrated so as not to seriously disrupt rail service, while also keeping construction workers safe.

Elaborating, he noted, as Aquadro did, that all rail service cannot be halted while crews for the railroads essentially remove or raise track, and the construction company that wins the bid for this stage of the project builds what amounts to a waterproof membrane around the nearly century-old tunnel. Instead, the work will be done in five stages, one set of tracks at a time, with CSXT actually laying some new, temporary track — known as a shoo-fly track — so trains can effectively travel around the work in progress.

This work is called positive-side waterproofing, said Aquadro, and it cannot be done in cold weather, which means the clock is ticking. Winter is eight months away, but that time will go by quickly, and Aquadro estimates it will take perhaps five or six weeks to complete each of the five phases.

“It’s a very tight timetable — there is very little margin for error,” he told BusinessWest, adding that the original starting date was April 1, which is now well in the rear-view mirror.

On the Right Track

Making the terminal building itself more weathertight will be much easier, said Aquadro, adding that water problems there were caused by leaks in the roof which will soon be addressed.

“And once it’s watertight, it’s sheetrock and studs, and off we go,” he said, referring to work to build out the old train station and its central concourse, which will have new and appropriate finishes and of obviously a more modern look.

The exterior of the building, while it still appears solid, needs some work as well, he said, adding that, when this project is completed, Springfield will have a unique and functional blend of old and new.

Like the trains that run above it, this project is all about moving parts, he noted in conclusion, and making everything run on time.

It’s a challenge — actually, a series of them — that he’s attacking head on.

George O’Brien can be reached at [email protected]