City to City

Taking Lessons — and Inspiration — from North Carolina

A group of 40 business and civic leaders from Greater Springfield were in two North Carolina municipalities — Winston-Salem and Greensboro — last week as part of the City to City program. As the name suggests, participants travel from one city to another, but they also take ideas and, hopefully, inspiration and determination back home. There were myriad thoughts expressed about what Springfield could learn from this excursion, but commentary centered around creating vibrancy downtown, focusing on steps to keep more young people in the 413 area code, crafting a more regional approach to economic development, and, perhaps most importantly, creating more positive energy in the City of Homes.Allen Joines was explaining — sort of — just how it came to be that 40 business and civic leaders from Greater Springfield were having breakfast at the Marriott in his city, Winston-Salem, N.C., listening to him talk about economic development, downtown revitalization, and generating business diversity.

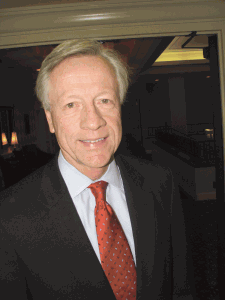

“The closer you get to the guillotine, the more you start to focus,” joked Joines, now in his ninth year as mayor of this city of 220,000, located about an hour from Charlotte.

‘Focus’ is a very general, perhaps overly simplistic way to describe what the leaders of Winston-Salem, or WS, as it’s called, did when, about 20 years ago, the bottom simply fell out of an economy based on tobacco, textiles, and furniture manufacturing, all industries on the decline. “We lost more than 10,000 jobs in about 18 months,” said Joines, who was then economic development director for the community. “In just a few years, RJ Reynolds [the tobacco giant headquartered in the city] went from 16,000 employees to under 3,000.”

Winston-Salem Mayor Allen Joines says his city has been quite resilient, bouncing back from a series of economic calamities.

Today, the manufacturing sector that once accounted for 45% of the jobs in Greater Winston-Salem now provides roughly 14%. Dramatic gains have been made in health care (now the largest employer), the biosciences (much of it happening at the Piedmont Triad Research Park created in the heart of downtown), the broad field of design, logistics and distribution, and others. Meanwhile, the city is making major strides in its efforts to become a center for something called regenerative medicine, or the engineering of tissue and organs (more on that later).

Over the past few years, the city has successfully attracted FedEx, which has built a regional air hub at nearby Piedmont Triad International Airport; prevailed in an intense competition to land a $426 million Caterpillar assembly plant; built a new baseball stadium downtown (not without controversy); opened dozens of new restaurants in the central business district; lowered its high-school dropout rate, and earned status as one of the few cities across the nation to curb, and actually reverse, the so-called brain drain.

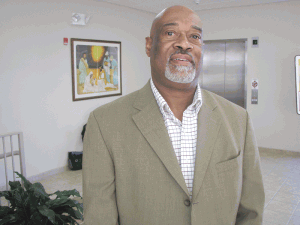

All this and more explains why those 40 leaders from Greater Springfield were in the Bethabara Room at the Marriott for the opening act of a program called City to City, where representatives of one (usually distressed) municipality visit another — to see, hear, ask questions, and, hopefully, take back some ideas and inspiration. Winston-Salem was chosen, said Ron Ancrum, president of the Community Foundation of Western New England and organizer of this junket, because it is like Springfield in many ways, including size, demographics, its status as a former manufacturing center, and recent challenges. Greensboro, a slightly smaller city 30 miles to the east, was chosen for the same reason.

A day after hearing about Winston-Salem’s progress, the Western Mass. contingent learned how Greensboro had waged a similar comeback in the face of deep losses in manufacturing jobs.

Reflecting on what they had absorbed in Winston-Salem on day two of the junket, participants had varying thoughts on what could be taken away.

Paul Robbins, president of the Wilbraham-based marketing and public-relations firm that bears his name, said the progress Winston-Salem has made in its downtown — with regard to everything from housing to new restaurants — and the resulting improvement in the retention of young people should prompt Springfield officials to redouble their efforts in that realm.

Meanwhile, Maryann Lombardi, director of Creative Economy for UMass Amherst, came away impressed not only with the large role the arts has played in economic development in Winston-Salem, but also how Wake Forest University, located within the city, has been part of virtually every initiative mentioned by leaders in that community and is a true “economic engine.”

Russ Denver, president of the Affiliated Chambers of Commerce of Greater Springfield, joked that he loved the city’s $11 commercial tax rate, less than one-third Springfield’s levy, and thought officials in the City of Homes might try such a number. Turning serious, he had high praise for the vision and creativity it took to put a 200-acre research park downtown.

Sally Fuller, project director for the Davis Foundation, was among many to observe that the overwhelmingly positive attitude and can-do philosophy in Winston-Salem stood in stark contrast to the negativism that she says prevails in Springfield and stifles progress.

Her remarks prompted many to nod in agreement, and Denver to summon a remark made by one of those carrying out the Urban Land Institute study on the city several years ago. “He said, ‘some people see the glass as half-full, others see it as half-empty; in Springfield, people believe they don’t even have a glass.’”

For this issue, BusinessWest recaps the City to City experience, focusing mostly on Winston-Salem, and on what participants want to take back from Tobacco Road. Their comments speak volumes about just how much work needs to be done in Springfield.

Changing the Landscape

Gayle Anderson says she’s like most chamber of commerce directors. She tracks what people say and write about her community, and takes great pride in placement on those ‘best of’ and ‘top 25’ lists that publications like to put together.

So she has a lot to be proud of these days, because WS is on many such compilations, including:

• ‘One of the Best Places to Live and Launch’ from 2008 in Fortune Small Business;

• The ‘Top 25 Places for Business and Careers’ as compiled by Forbes in 2009;

• The ‘Top 25 Locations for Biotech’ as assembled by Business Facilities magazine in 2009; and

• The ‘Top 7 Intelligent Communities in the World’ as compiled by the Intelligent Community Forum in 2008.

Meanwhile, the New York Times reported earlier this year that WS is one of only 14 cities across the country with more college graduates moving in than moving out, and North Carolina was listed on the most recent ‘Top Destination States for People Relocating’ list put together by United Van Lines.

“We didn’t get all of those people, obviously, but we certainly got our share,” said Lombardi, who like Mayor Joines and others, said Winston-Salem has come a long way over the past 20 years, and even a decade ago, when West Fourth Street, on which the WS chamber is located, was, in her words, “dead as a doorknob.”

How the business district, and the city as a whole, has come back to life, is a compelling story, one that placed WS in a 23-page report authored by Federal Reserve Bank of Boston called “Lessons from Resurgent Cities,” and garnered the attention of Ancrum as he and others considered possible destinations for a City to City tour involving Springfield area leaders.

Ron Ancrum says the City to City tour was a learning expereince, but also a chance for participants to get to know one another so that they might better work together to implement what they've learned.

Several destinations were considered for the City to City experience, Ancrum continued, noting that two in New England — Providence and New Haven — while meritorious, were rejected because the committee planning the program thought it would be difficult to get business leaders to commit to a three-day itinerary, which is the preferred length of such visits, in cities so close to home.

After considering Jersey City, N.J., a community in Michigan, and several others, the planning committee chose Winston-Salem and Greensboro because of both geography and their many similarities to Springfield. The tour would ultimately have four learning focal points: education, economic development, arts and culture, and public safety.

Ancrum said he and others had many goals in mind when they put the trip together. First among them was providing a learning laboratory of sorts, but there was also the desire to bring business and civic leaders together so that they may get to know one another, talk about their experiences, and then perhaps ultimately work together to help put some of the concepts they’d seen in North Carolina to work in Greater Springfield.

Participants visited a number of locations over the three days, including the research park; the WS chamber complex; the Milton Rhodes Center for the Arts, a renovated former Hanes underwear plant now home to galleries, meeting and event spaces, the Sawtooth School for Visual Art, and the Hanesbrands Theatre; the Goler Community Development Center in WS; Bennett College in Greensboro; the International Civil Rights Museum, also in Greensboro; and other stops.

Rolling with the Punches

As he recounted Winston-Salem’s near-miss with the guillotine, Joines said the city’s comeback — still very much a work in progress — has been marked by diligence and creativity, but even moreso by resiliency.

“When I look back on all that we went through, I think of that kid’s toy, the one where when you punched it, it would fall over, but then bounce back up again,” he explained during his opening remarks. “We took a lot of punches — and we still get punched today — but we’ve always bounced back up.”

Joines said he was a somewhat reluctant mayoral candidate, but was eventually compelled to run because he didn’t think city government was moving the city in the right direction. Running with the slogan ‘One City Pulling Together,’ Joines took nearly 80% of the vote in his first election.

Since assuming the corner office, Joines says he has focused economic-development activity on job creation in seven identified sectors:

• Financial services, in which the city already had a solid base, with Wachovia, recently acquired by Wells Fargo, headquartered there;

• Health care, a sector dominated by two large medical centers, including one at Wake Forest;

• Biomedical, an emerging sector that the mayor believes may yield more than 30,000 new jobs. This sector has been bolstered by the creation of the PTRP, which is anchored by the Wake Forest University School of Medicine’s Department of Physiology and Pharmacology and now boasts more than 20 companies;

• ‘Design,’ a term that applies to the design of everything from clothing to furniture to medical devices, and has become a steady source of new jobs, said Joines;

• Advanced manufacturing;

• Logistics and distribution, a field bolstered by the arrival of FedEx, which has a history of attracting to its hubs companies that depend on overnight shipping, and the same is expected for Greater Winston-Salem; and

• Travel and tourism, which has historically been a reliable source of jobs.

Growth has come in fits and starts over the past 20 years or so, said Joines, noting that, after a great deal of activity in the mid- and late ’90s, things were slowed by the recession that followed 9/11. Meanwhile, the severe downturn of 2008 and 2009 also took a toll on several sectors, especially travel and tourism.

But there has been growth across those seven sectors, he said, adding that, despite measurable progress, city leaders were not satisfied. They studied 108 other communities, focusing mostly on 17 metropolitan areas that were growing twice as fast as WS.

“We wanted to determine if we were going at things the right way,” said Joines. “We looked at these cities to see what they were doing differently that we might do. We determined that what set them apart was a driver, or magnet, that was ruthless.

“And we set about creating our own driver,” he continued, adding that such an economic force would have to meet several criteria. “We had to ask ourselves, ‘is it feasible, is it unique, and is it impactful?

Eventually city leaders would answer ‘yes’ in each case to the field of regenerative medicine, which, says Joines, could eventually create perhaps 20,000 or 30,000 jobs.

The nucleus for this ‘driver’ is the Wake Forest Institute for Regenerative Medicine, led by Dr. Anthony Atala. The institute is an international leader in the engineering of multiple types of human tissue, allowing for the growth of replacement organs and transplanting them into patients.

“We’re galvanized around regenerative medicine,” said Joines, adding that the city now hosts all major conferences involving this field. “We believe that this is going to be a great source of growth and jobs for us.”

Young Ideas

To keep its many sources of jobs thriving, from a workforce perspective, WS officials realized that they had to do something to retain more young people and attract some from outside the region. “Jobs are the best way to do that,” said Anderson, adding quickly that the city has made major progress in creating well-paying jobs in exciting, potential-laden fields.

But there are other factors involved in attracting young people, she said, especially the need to create the kind of vibrancy that this constituency demands. With that in mind, city officials went to work downtown.

Some market-rate housing was created, and there are plans for more, Anderson continued. Meanwhile, an ambitious restaurant-loan program involving area banks and the Downtown Winston-Salem Partnership was created to help boost the hospitality sector. Despite the volatility and high failure rate in the industry, only a few of the ventures that have received funding have folded, she told BusinessWest, and, at the moment, there are no restaurant-ready sites left downtown.

Beyond new restaurants and clubs, the city has scheduled a number of events downtown, said Jason Theil, president of the downtown partnership, noting that these happenings introduce the central business district to people and reinforce the notion that it is a good place to live, work, and play.

He said that any city looking to thrive must place a heavy emphasis on downtown development because it is the central business district that often defines a community.

“When you think about it, it’s a city’s skyline that you see in many pictures and postcards and marketing materials,” he explained. “The downtown is a reflection of how a community sees itself. Each one is different, each one is unique, each one gives a city its identity.”

To create still more vibrancy downtown, city officials, working with private developers, crafted plans for a baseball stadium. But halfway through construction, amid plans to double the size of the facility, the Great Recession hit and work ground to a halt, and Jones knew he had to get it started again.

“If we didn’t finish it, 60,000 people would be looking at failure, and we didn’t want that,” said the mayor, referring to the number of commuters who pass that site every day.

City officials eventually pumped more than $20 million in public funding into the project, drawing criticism from many quarters as they did so. But today, the public is supporting the park, filling it for most all the games played there to date, said Jones, adding that the ballpark struggle is a prime example of the resiliency he spoke of early and often.

That resilience has been one of the factors that have keyed Winston-Salem’s turnaround, said Bob Leak Jr., president of Winston-Salem Business Inc. (WSBI), an economic-development group focused on attracting and retaining businesses that he described as a “marketing agency.” When asked to list some of the others, he mentioned everything from that low commercial tax rate and comparatively low cost of living to an attractive workforce; from all the improvements made downtown that are attracting young people to the fact that North Carolina has the lowest percentage of union representation among its workforce in the country.

It is a package of benefits more than any single factor that has led to the city’s resurgence, Leak said, adding that financial incentives, in the form of tax breaks and other provisions, are, while important, just part of the equation.

“Right now, labor and facilities are the two most important factors,” he said, listing some others, such as energy costs, transportation, and schools. “Incentives are important, but not at the start, because if you don’t have the labor or the physical location or the other operating advantages, there’s not enough money you can throw at it for a long enough period to make it work.”

Meanwhile, a decidedly regional outlook on economic development has certainly helped as well, he said, adding that, while the WSBI is essentially selling WS, in many instances it first has to sell the Winston-Salem/Greensboro/High Point region, and its salability helps open doors.

Gaining Perspective

As she got up to leave at the conclusion of one of the sessions in Winston-Salem — this one involving the city’s Housing Authority and the Goler Community Center, both of which are involved in outside-the-box housing projects — Joan Kagan, executive director of Square One in Springfield, turned to BusinessWest and said, “this is a city of collaboration and creativity.”

Those were the two words heard most often amid discussion and reflection on the part of those in the Springfield contingent. Others included Joines’ favorite, ‘resilient,’ as well as ‘energetic’ and ‘imaginative.’

Overall, participants were impressed with the level of cooperation among the various players in the public and private sectors, including major corporations like RJ Reynolds and institutions like Wake Forest, and wondered out loud how to bottle it and bring it home.

While most in attendance considered many of the things WS has accomplished, such as the research park and landing Caterpillar, beyond Springfield’s reach, they said the real lessons from the city are to create a working plan, and then summon the wherewithal to carry it out.

“I think that’s the biggest thing I’ll take back from this,” said Ancrum. “I think we’ve seen the importance of having a plan and having everyone on the same page with that plan.”

For Robbins, the work done downtown, and its impact on overall vibrancy and the retention of young people, was perhaps the biggest takeaway. In recent years, he said, there’s been a ‘downtown versus the rest of the world’ mentality that needs to end.

“The neighborhoods don’t think we need a downtown, the suburbs don’t think we need a downtown,” he explained. “What we’ve seen here [in Winston-Salem] is that, to have a vibrant community, you must have a core center city that people want to go to. Cities are hot again, and the proof is right here.”

Bill Ward, executive director of the Regional Employment Board of Hampden County, came away impressed with the candor of Winston-Salem officials, who, he said, weren’t afraid to talk about failures, and there have been many, nor were they taken down by them.

“They never let failure get in the way, and we can learn from that,” he said, while also making note of the many times Joines and others made use of the phrase ‘collaborative leadership.’

“Those words have also been heard in Springfield,” he said, adding that, for the most part, people are talking about it, not doing it. “We have to drill down and figure out exactly what that means.”

For Fuller, the positive energy in WS is palpable, and something Springfield needs to create for itself.

“We have so many of the ingredients in place,” she said, referring to downtown specifically but also the city as a whole. “But what we seem to be lacking is the excitement. Here [in Winston-Salem] people feel they can make things happen. In Springfield, I think we’re down on ourselves; we spend too much time agonizing about what we can’t do.”

On the Cutting Edge

A decade ago, Joines said, Winston-Salem certainly wouldn’t have been a destination for any City to City tours. It had escaped the guillotine he mentioned metaphorically, but most of the major success stories were still to be written.

The fact that the city is now hosting groups like the one from Springfield in its Marriott should provide some additional inspiration to those who took this trip, he said. And, indeed, some of those who listened to the mayor expressed the optimism that someday, probably no time soon, the City of Homes may just be on the other side of the City to City equation.

To get there, though, it appears that the city will first have to find a glass, and then make sure people consider it at least half full.

In other words, and to sum up and paraphrase those who took this excursion, there must be more focus.

George O’Brien can be reached

at [email protected]