His March is Changing The Conversation on Food Insecurity

Sean Barry recalls listening to the first few editions of Monte’s March on the radio. (Photo by Leah Martin Photography)

Sean Barry recalls listening to the first few editions of Monte’s March on the radio. (Photo by Leah Martin Photography)

What he remembers most is how Monte Belmonte, the radio personality who created this unique publicity stunt to raise money for the Food Bank of Western Massachusetts, seemed to keep getting lost on his trek from Northampton to Greenfield.

“That first year, I was listening to him taking wrong turns … I thought to myself, ‘maybe he needs help,’” said Barry, owner of Four Seasons Wines & Liquors in Hadley. “The second year, the march snuck up on me, so I wasn’t able to sign up. So again I listened, and I believe I heard him getting lost again — he didn’t seem to have a clear idea of where he was.”

Anyway, the more Barry listened, the more he wanted to be part of what Belmonte was doing.

“I’m a true believer in what the Food Bank does and how unfortunately necessary it is,” he said, adding that he secured enough coverage at the store to be able to march in the third event, and he’s been back every year since. He now carries out an important role in this curious and all-important spectacle — keeping the souped-up shopping cart pushed by Belmote out of harm’s way.

“I’m the one you see in the pictures with my hand on the cart, steering it so Monte doesn’t have to worry about it hitting a tree or getting it stuck in a pothole,” he explained. “That leaves Monte to do what Monte does best.”

In a way, Barry’s growing involvement with the march is a microcosm of its growth and evolution over the past decade. It started small, but almost immediately it caught people’s attention — and kept it. And then, they wanted to be part of it in some way. And all kinds of groups and individuals have found a way, helping to raise more than $1.2 million to date.

“Through his various efforts and interviews, people come to understand the complexity of the problem and the diversity of the problem. It’s not a once-a-year thing — he’s creating a movement, and he’s creating awareness.”

The ranks include lawmakers, especially U.S. Rep. Jim McGovern, the Democrat from Worcester, who marches alongside Belmonte every year, as well as state representatives and senators. And school children, who have been inspired to raise money for the cause in many different ways and even hand over their allowance to Belmonte as he marches by. And the famous UMass marching band, which has joined the trek in downtown Amherst.

While on his march, Belmonte is, as they might say in the military, on point. That means he’s at the front of the line — actually, Barry is at the very front — usually interviewing one of those elected officials or kids as he’s conducting a radio show. In other words, he’s multi-tasking and looking forward, to the real estate in front of him.

That means that he’s generally unaware of just how many people have joined him for the march in a manner that has prompted some to compare him to the pied piper and others to Forrest Gump in that famous scene where he’s repeatedly running across the country.

Later, after the march is over and he sees photos, he’s often taken aback by just how much company he has.

“When I see that breadth of humanity behind us, it’s really overwhelming to me,” he said, adding that he’s also quite struck by how many people have “taken ownership” of the need to raise money for the Food Bank through their own initiatives — ranging from one brewery owner’s 50-mile run to a solidarity march conducted by students and teachers at Conway Elementary School, to one woman’s march in Antarctica (because she was visiting there the week of the march).

Monte Belmonte, seen here with U.S. Reps. Richard Neal, left, and Jim McGovern, gets set to start another of his marches. (Photo from Matthew Cavanaugh)

But while this event has grown to attract hundreds, and perhaps thousands of participants and supporters, Belmonte has been the individual most responsible for its success and its ability to keep food insecurity front of mind — not for two days in November, but all year.

McGovern perhaps said it best when he told BusinessWest that Belmonte hasn’t created a march — he’s created a movement.

“It’s a movement to not just be there in this fight against hunger during Monte’s March, but all year round,” the congressman explained. “Through his various efforts and interviews, people come to understand the complexity of the problem and the diversity of the problem. It’s not a once-a-year thing — he’s creating a movement, and he’s creating awareness.”

And those sentiments clearly explain why Belmonte is a member of the Difference Makers class of 2020.

Walking the Walk

Belmonte calls it ‘Amity Hill Horror.’

That’s meant to be a blend of The Amityville Horror, the movie, and Heartbreak Hill, the notorious stretch of the Boston Marathon in Newton that taxes the runners because of its sharp incline, and describes one of the only real physical tests along Monte’s March — the climb up Amity Street to the center of Amherst.

“Pushing up that hill and trying to broadcast is a bit of challenge,” said Belmonte, noting that Barry, whom he refers to as his ‘Sancho Panza,’ helps him navigate that climb and, overall, keep him on track.

Belmonte now has plenty of company as he attacks that hill with his shopping cart — outfitted for long-distance travel by students at Smith Vocational High School in Northampton — and that’s just one way to measure how far this march has come, and how impactful it now is. But there are many others.

Starting with the number $333,333.33.

That was the fund-raising goal for the march in 2019. It’s an odd number, one packed with significance, because those at the Food Bank estimate they can provide three meals for each dollar raised for their organization. Thus, this became the ‘march for a million meals’ — and the money it takes to provide them.

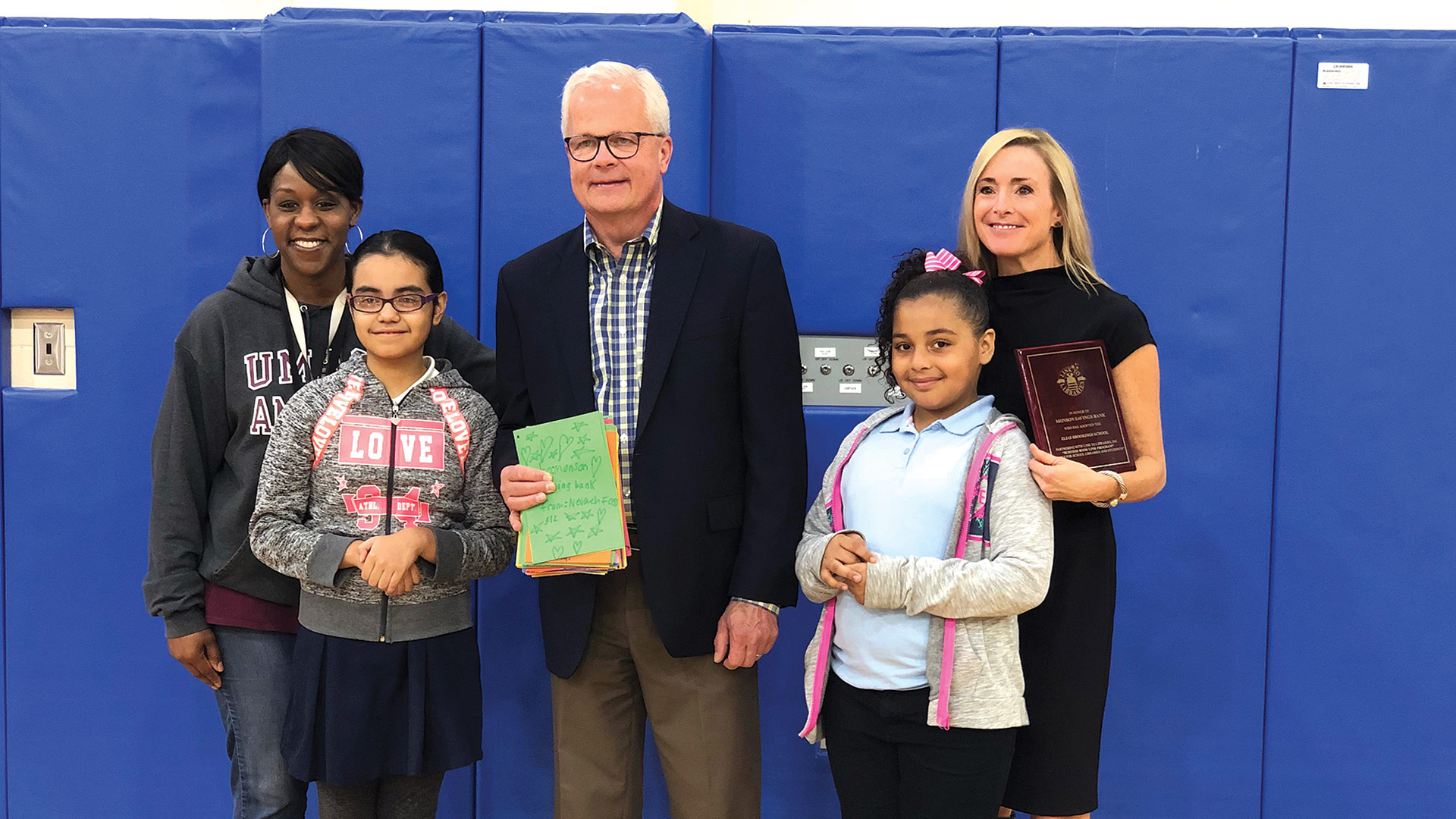

Over the years, Monte’s march has drawn ever-growing numbers of marchers, one of many indicators of how it has become a force in the fight against food insecurity.

(Photo from Matthew Cavanaugh)

“We had a lot of fun with it. We used that number — $333,333.33 — a ton, and people really gravitated toward it; we got a lot of $33 donations and $333 donations,” he said, adding that bestselling author and illustrator Mo Willems and his wife, Cher, who live in Northampton, pledged $33,333.33 “because they’re generous, but also because they love the schtick.”

As he talked about the march, Belmonte said it was hard to imagine those kinds of numbers back in the beginning when this wasn’t actually a march. Indeed, efforts to help the Food Bank of Western Massachusetts with a fundraising ‘publicity stunt,’ as he called it, started with Belmonte standing with a shopping cart in front of Whole Foods Market soliciting donations of food items.

When those at the Food Bank noted that, with that organization’s buying power, it could do much more with cash than it could with donated food, the focus eventually shifted to Belmonte pushing a cart from Northampton to Greenfield, soliciting donations as he went over the air.

As Barry’s comments earlier indicate, it took a few years for this endeavor to find its way — figuratively, but also quite literally.

“The first two years, I basically did it all by myself,” Belmonte recalled. “It was me, a shopping cart, a station van to make sure I didn’t get hit from behind, and a guy with a flashlight when the sun went down to make sure people could see me well enough.”

But from the beginning, the march resonated with people — and raised healthy sums of money. Over the years, it continued to pick up speed — and supporters, and donations.

In recent years, it has become a truly regional phenomenon as the march was extended from one day to two, from 26 miles to 43, starting in Springfield’s Mason Square, specifically Martin Luther King Jr. Family Services, led by another of this year’s honorees, Ronn Johnson (see story, page 35).

Positive Steps

But while the march has succeeded in garnering donations of all sizes and from a wide range of individuals and groups, its impact has gone well beyond money and the meals it buys.

Indeed, those we spoke with said Belmonte, his march, and his efforts before and after the annual trek have shed much-needed light on the subject of food insecurity.

“One of the great things about the march and the lead-up to it is Monte spending a great deal time on the radio and in public forums talking about the problem of hunger and food insecurity, and talking about the faces of the hungry in our community,” said McGovern. “And by doing that, he helps dispel those stereotypes that have become common in right-wing media; the reality is, hunger defies stereotypes. We live in the richest country in the world, and yet there are 40 million of our fellow citizens who don’t know where the next meal is coming from.

“People you’re working with may fall into that category of being food-insecure or hungry,” he went on. “And if you talk with teachers, you’ll come to understand the realities they see in their classrooms — kids who come to school on Mondays and can’t concentrate because they haven’t eaten all weekend or who ask for food on Fridays so they’ll have something to eat. And there are people who work full-time but make so little money they still qualify for SNAP benefits.”

Through his platform as a radio personality, Belmonte has broadened the discussion on hunger and taken it to a higher level, said McGovern. “The fact that he has some celebrity enables him to bring in people who might not otherwise gravitate to this issue.”

Andrew Morehouse, executive director of the Food Bank of Western Massachusetts, agreed, and said Belmonte, now a member of the Food Bank’s Coalition to End Hunger, has taken his efforts well beyond the fundraising level.

“He’s been involved in an ongoing effort over many years to conceptualize and put into action long-term solutions,” he noted. “He’s learned a lot from it, and he’s been involved in a very different way, not just raising money and awareness.”

When asked about what the march that bears his name has accomplished, Belmonte said that, beyond inspiring people to write checks, it has prompted them to rethink this problem and join the effort to confront it.

“My hope is that more people will think differently about what it means to be hungry, and what it means to be poor,” he told BusinessWest. “No one wants to be hungry forever; no one wants to be on SNAP or food stamps forever. Most of the people who are on it are working and need help for a short amount of time. To demonize those people, who are in many cases children, the elderly, disabled people, veterans, and others who just need help for a little while, is wrong.

“Overall, I want to people to know that the Food Bank, and hopefully our government, has their back and will give them help when they need it,” he went on. “But I’m hoping more people will hear these stories from these people during the march and surrounding the march and change the way they think about poverty, being poor, and needing help — and pitching in when they can.

“As Jim McGovern loves to say, we could end hunger in this country, but we lack the political will,” he said in conclusion. “So I guess the goal of the march is to change hearts and minds about what it means to be hungry.”

Food for Thought

Monte Belmonte doesn’t have to worry about getting lost anymore.

He knows the route by heart now, and besides, he has lots of company, including Barry, with his hand on the shopping cart, guiding it away from potholes.

All this company, and the many forms it takes, is symbolic of how the march has grown and evolved, and how it has come to do much more than raise money for the Food Bank.

As McGovern said, it’s more than a march, it’s a movement — one that’s bringing a problem to light and maybe, just maybe, someday to an end.

George O’Brien can be reached at [email protected]

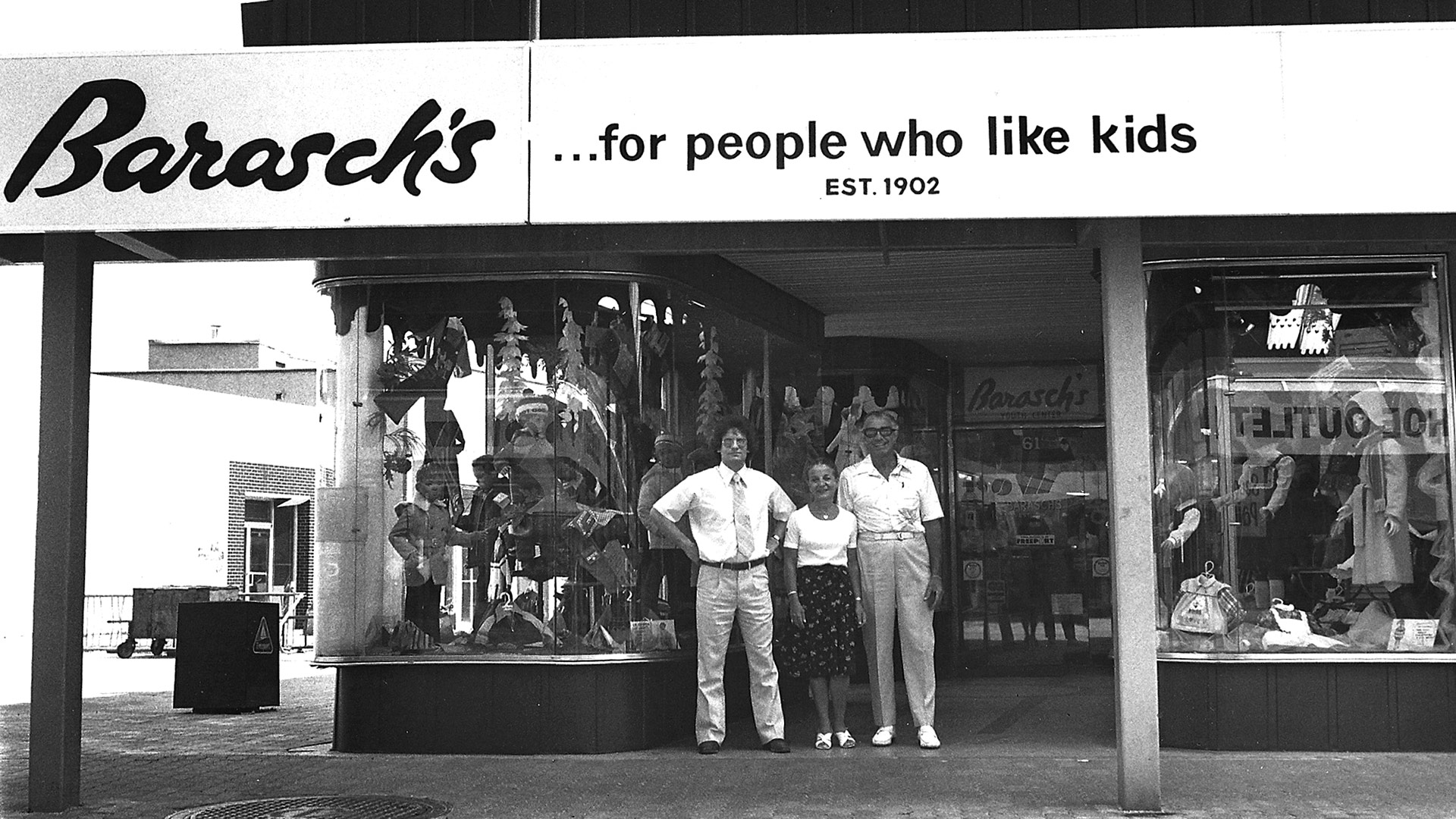

Christopher ‘Monte’ Belmonte

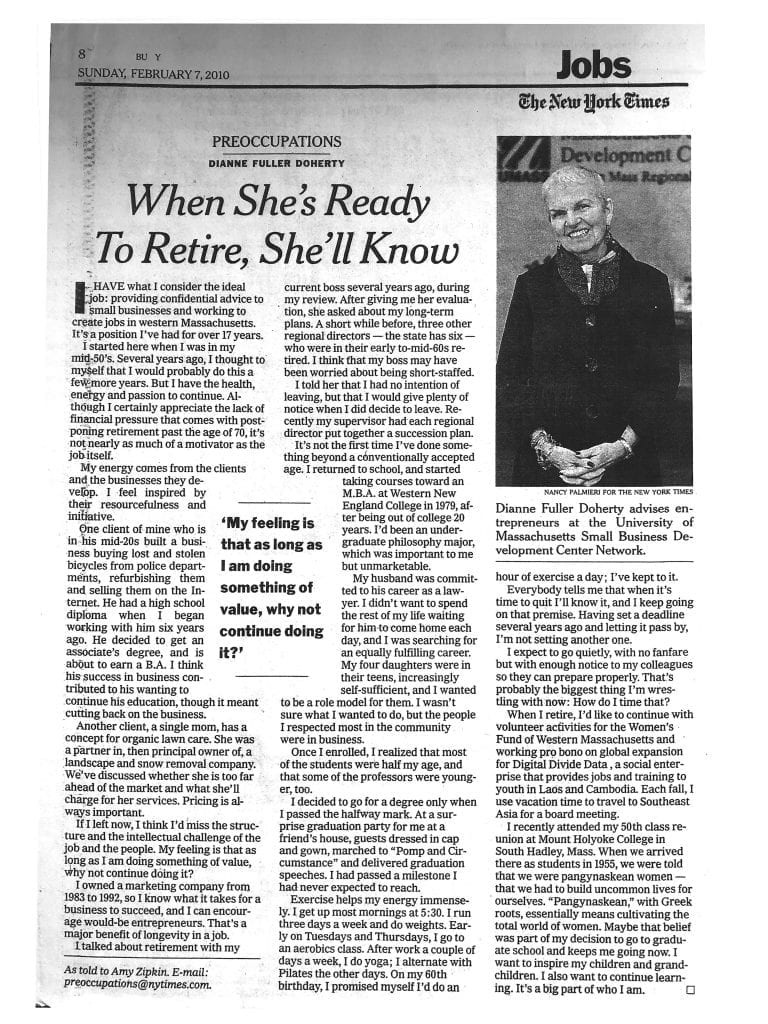

Christopher ‘Monte’ Belmonte Ira Bryck

Ira Bryck Dianne

Dianne

Sean Barry recalls listening to the first few editions of Monte’s March on the radio. (Photo by Leah Martin Photography)

Sean Barry recalls listening to the first few editions of Monte’s March on the radio. (Photo by Leah Martin Photography)