Here, Shared Research by Nurses and Engineers Will Benefit Patients Everywhere

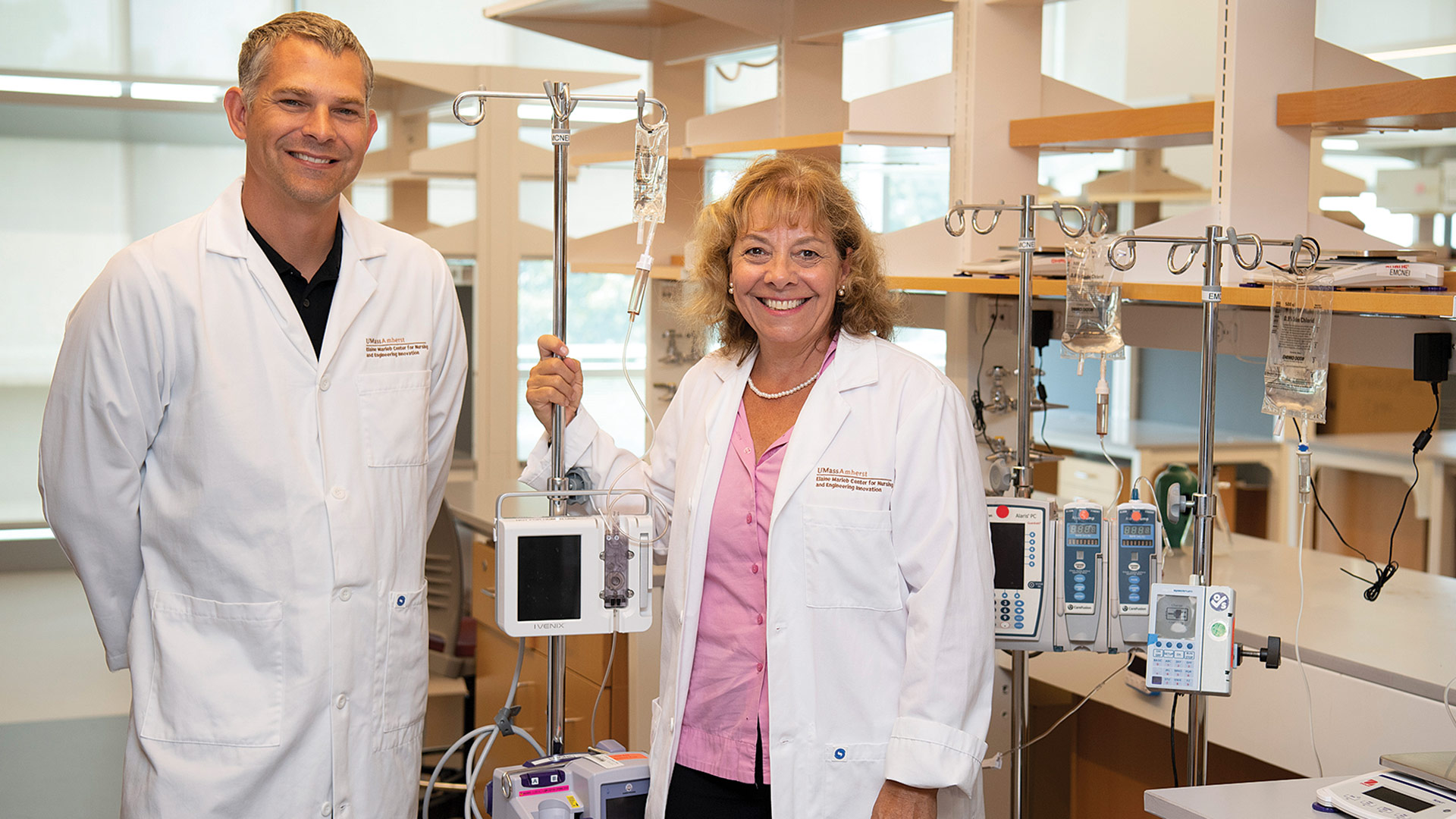

Co-directors Frank Sup and Karen Giuliano. Leah Martin Photography

Intravenous (IV) infusion pump systems are among the most recognized technologies in healthcare, used by about 90% of hospital patients.

They’re also hopelessly out of date, Karen Giuliano said.

“The design has been around a long time, and hospitals don’t buy one; they buy an entire fleet. They have to invest in training, service contracts, and IT infrastructure. To install a platform is a huge investment and effort.”

And that has led to stagnation, she added. “Over 80% of pumps are really old platforms and don’t do the job they need to do. They’re not developed for today’s standards.”

Enter the Elaine Marieb Center for Nursing and Engineering Innovation at UMass Amherst, which has made improving the safety and usability of IV smart pumps one of its first major projects. The team has been exploring flow-rate accuracy in a variety of settings and use cases, with the goal of developing pumps that eliminate inaccuracy, inconvenience, and resulting medical errors through new technology and simplified design.

The work is gaining widespread attention, as Giuliano, co-director of the center and associate professor of Nursing, and postdoctoral research fellow Jeannine Blake were recently recognized by the Assoc. for the Advancement of Medical Instrumentation (AAMI) for the Best Research Paper in 2021.

Their paper, “Nurse and Pharmacist Knowledge of Intravenous Smart Pump System Setup Requirements,” explored knowledge of intravenous smart-pump system setup requirements among nurses and pharmacists. The results were published in Biomedical Instrumentation & Technology, AAMI’s peer-reviewed journal.

“There’s already a critical nursing shortage, fatigue, and burnout. How can robotics be used to maybe alleviate some of those problems? We can use robotics as an extension of the nurse.”

“We don’t want to build a new pump; we want to build a set of requirements for manufacturers that have been sitting idle for too long without being forced to innovate for the safety of patients and the workflow of the nurses,” Giuliano told BusinessWest.

The effort demonstrates the types of innovation she and Frank Sup, associate professor of Mechanical and Industrial Engineering and the other co-director of the Elaine Marieb Center for Nursing and Engineering Innovation, intended when they launched the center in early 2021. It also reflects the cross-educational opportunities for people like Blake, the first nursing doctoral student to enter an engineering postdoctoral fellowship at UMass.

“Students have come out of here with a siloed education, nurses and engineers. There’s not a natural inkling to work together; they might not even know the importance of collaborating in that way,” Giuliano said. “What we want is to have students graduate that already have that in common, to reach across the aisle. The healthcare environment should not be a silo.”

Under Sup’s leadership, the center has also begun research on the use of robotics in healthcare. It teams doctoral students from both engineering and nursing, as well as an undergraduate nursing honors student, to identify challenges and develop robotic solutions to improve healthcare delivery for patients and providers.

The incorporation of robotic technology into the healthcare system is ongoing and already includes innovations like fully autonomous disinfecting systems and invasive surgical devices, and Sup feels it’s essential that these new technologies are integrated into the field of nursing at multiple levels, including hospital administration, the clinical workplace, and university education. And students need to interact with robots to better understand and utilize this technology in a controlled setting before patient care is involved.

“What are robotics, what can they do, what are they good for, and how can we start to train nurses and engineers in robotics? What day-to-day situations might nurses face in the hospital, clinic, and home, and what might be the best use cases for these robotics systems?” he asked. “That’s where this program started. Nurses are not typically trained in robotics, so we actually start to expose them to these things.”

That may seem like a scary thought to some, or imply that robots could replace nurses, but that’s far from the case, Sup added.

“There’s already a critical nursing shortage, fatigue, and burnout. How can robotics be used to maybe alleviate some of those problems? We can use robotics as an extension of the nurse, potentially doing things when they’re not there, like monitoring and lower levels of service.”

By bringing nurses and engineers together at the earliest stages of product innovation, the Elaine Marieb Center promises a raft of such breakthroughs that will result in better technology and, more important, better patient care.

Come Together

This is how Giuliano and Sup described the center’s mission at its opening last year:

“Today, healthcare technologies are too often made without the insights and understanding that clinicians bring to the table. Nurses are end users, facing healthcare challenges on the frontlines of patient care. Engineers have the expertise and skills to envision and create medical devices and can work with nurses who bring the real-world healthcare experience needed to design the best possible products and solutions.

“This transformation depends heavily on collaborative research and development work among nursing, engineering, and other disciplines,” they went on. “The ability to quickly and effectively develop and test innovations requires both nursing and engineering skillsets. The power of the nurse-engineer approach is derived from the mutual collaboration between the two, where the nurse identifies the problem, and the engineer facilitates potential solutions.”

One problem in the past, both of them explained to BusinessWest, was that products too often wound up in the hands of nurses too far along in the design and development process to change very much.

“I realized how important it was to have a front-end-user perspective built into the products rather than trying to back-engineer it when it’s 90% done.”

Giuliano, with more than 25 years of experience in critical-care nursing, medical product development and innovation, and patient-centered clinical outcomes research, should know. Prior to joining UMass Amherst, she spent many years working on medical product development from an industry perspective, including 12 years with Philips Healthcare.

Early in her career, she said, “I realized how important it was to have a front-end-user perspective built into the products rather than trying to back-engineer it when it’s 90% done.”

Now, at the center, “we have the ability to prototype things and test them in nursing simulation labs and test them in actual hospitals,” she added, the latter through a collaboration with Baystate Health.

Meanwhile, Sup was also a natural choice to co-direct the new center. As director of UMass Amherst’s Mechatronics and Robotics Research Lab, his research has long focused on developing human-centered mechatronic technologies for augmenting human performance and exploring how to enable robots to fluently interact physically with humans. To that end, he brought teams of nursing and engineering students together to work on senior capstone design projects.

The model was formalized as the Elaine Marieb Center for Nursing and Engineering Innovation with the help of two major gifts: $1 million in seed funding from alumni Michael and Theresa Hluchyj, longtime supporters of both the College of Engineering and the College of Nursing; and $21.5 million from the Elaine Nicpon Marieb Charitable Foundation to the College of Nursing, with a significant portion designated to support the new center.

“Innovation is often accelerated at the intersection of different academic disciplines,” Michael Hluchyj said when announcing the first gift. “The worldwide health crises resulting from the COVID-19 pandemic make clear the critical need for innovative solutions in clinical settings where both nursing and engineering play vital roles.”

And nurses need to have a seat at the innovation table early, Giuliano said.

“Nurses use more products and are part of more services than any other healthcare provicer,” she told BusinessWest. “If they’re not at the table, you’re not going to have the right products. They’re not going to be usable, and if they’re not usable, then they don’t do the job. And from an economic standpoint, they don’t generate the revenue that the company wants. So it’s a lose-lose, which we can turn into a win-win.

“We want to be a usability testing center,” she went on. “So if a company has a product at a certain point in development, has an idea what’s supposed to do and how it’s supposed to work and what its value is, we literally bring it into a sim lab.”

The usability test involves two people, a nurse and a volunteer patient, and both evaluate it, as test administrators watch how it’s used. “If the same mistake is made over and over, it’s a design flaw; it’s not a user error,” Giuliano explained. Then all those results and perceptions go back to manufacturer, who has the opportunity to make improvements early in the process.

To that end, the emerging product prototyping laboratory on the Amherst campus will enable students to design and prototype new products, while a proposed usability laboratory on the Mount Ida campus will allow for product and service testing by frontline clinical end users.

“Having a better understanding of frontline clinician knowledge is a fundamental part of our overall program of research on improving the safety and usability of IV smart pumps,” Blake said when she and Giuliano received the AAMI’s award for their research earlier this year. “We are very excited to receive this award, which supports our continued efforts in this important area of research.”

Promising Outcomes

Better research resulting in better patient care is the goal, whether it’s IV pumps, robotics at the hospital bedside, or any number of other ongoing projects at the center, from cloud-based home-healthcare monitoring to wearable sensors that record body movement to assess chronic pain.

Part of the center’s raison d’être is that nurses and engineers are both trained problem solvers who rely on innovation to find solutions, but their paths rarely cross, and the timeframes required for them to find solutions are dramatically different.

Giuliano got her PhD while at Phillips Healthcare because “I really wanted to be a better researcher so I could test products in a meaningful way.” Later, she added, “I realized I liked academia — I was a better student as a 40-year-old than as a 20-year-old — and I knew I wanted to go into academia and try to recreate the nurse-engineer pairing in the academic environment.”

By teaming up with Sup, who was already pursuing those connections, and with the help of some generous gifts from supporters who saw potential in this model, a center was created that is not only generating some impressive outcomes, but is paving a new way for diverse minds to collaborate and improve the patient experience across the globe.

“The whole idea of this center is for academic clinicians, students, nurses, and doctors to bring in industry partners,” Sup said. “It’s going to be innovative, and it’s going to make a difference.”

And it clearly lives up to the title of Healthcare Hero in the category of Innovation.

“This work that’s being done will make its way to safety standards everywhere,” Giuliano said. “Nobody else is doing that. It’s huge.”

Joseph Bednar can be reached at [email protected]