Why Solar Arrays Are the Hot Trend in Energy Production

Here Comes the Sun

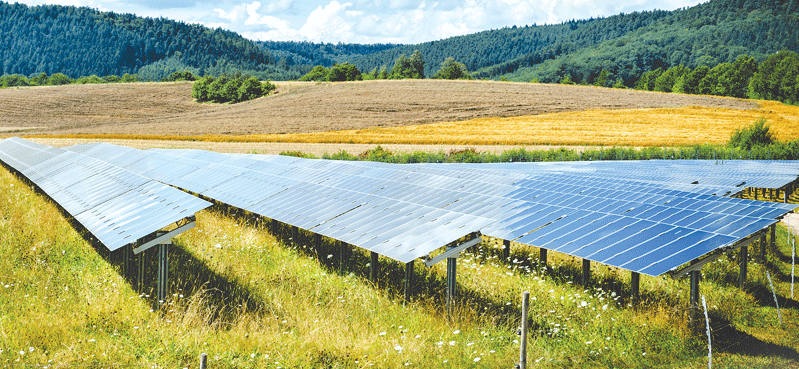

Solar power is enjoying a heyday in Massachusetts right now, as home and business owners, buoyed by state incentives, seek greener energy options, and — most visibly — as cities and towns scramble to strike deals with energy companies on large-scale photovoltaic arrays, usually on otherwise undevelopable parcels, such as landfills. The projects don’t create many jobs, but they do bring tax benefits for communities, profits for the developers, and satisfaction for anyone who values a move away from fossil fuels.

Before work began to convert 219 Russellville Road in Westfield into a solar farm, the property was home to more than 60,000 cubic yards of concrete and road material, piled high.

“This property was a construction yard for many years, taking on construction materials from roads that were ripped up,” said Joe Mitchell, the city’s advancement officer and director of economic development. “The yard would pulverize the materials and use them on different jobs. As time went on, this property blighted, with piles of construction debris.”

Additionally, topsoil was removed from the site over the years, creating wetlands. In other words, the property, owned by J.W. Cowls Construction, had become undevelopable.

Enter Con Edison, which built a 10-acre solar array on the site, which opened in the fall. Before doing so, it paid to remove those piles of debris, mitigated the affected wetlands by creating other wetlands nearby, and worked with the Conservation Commission and the state Department of Environmental Protection to clean up petroleum that was discovered on site.

“Once they cleaned up the environmental issues, they were able to put this undevelopable property back on the tax rolls, creating green energy for everyone to use,” Mitchell said.

From left, Joe Mitchell with Westfield Mayor Brian Sullivan and Community Outreach Coordinator Amber Dahaney at the ribbon cutting for Westfield’s latest solar project.

At the end of 20 years, Con Edison will remove the panels, and the property owner will be able to do what he wishes with the site — whether that’s another solar project or a completely different use, but certainly something more amenable to the neighbors than a dumping ground for giant piles of asphalt.

The city of Holyoke also recently dedicated a solar project, this one a 22-acre array — set to go live later this month — at Mt. Tom along the Connecticut River beside a decommissioned coal-generation facility.

The owner, ENGIE North America — formerly known as GDF SUEZ Energy North America — shut down the coal plant two years ago after years of sporadic operation; burning coal to produce energy had become too expensive. The 5.76 megawatts of energy generated at the solar farm — enough power to supply 1,000 homes — will be sold to Holyoke Gas & Electric (HGE) at or below market rates.

Meanwhile, under a PILOT (payment in lieu of taxes) agreement, the city will receive $28,000 for the solar panels, as well as normal tax revenue on the property. The reason is that solar panels have a high initial valuation but depreciate quickly, so locking in an annual payment of $5,000 per megawatt ensures a steady flow of revenue.

“We had to find a way to offset the cost of decommissioning the coal plant, and then find a way to make a solar project economically viable,” said HGE Manager Jim Lavelle, explaining that the utility forged a power purchase agreement (PPA) with ENGIE to ensure that residential customers benefit through lower energy rates.

Jim Lavelle says the Mt. Tom solar project offsets the revenue losses from the decommissioned coal plant while creating more carbon-free energy in a city already known for its hydroelectric power.

But another benefit is, quite simply, lowering the city’s carbon footprint. With its dam on the Connecticut River and system of canals downtown already providing two-thirds of its energy, about 90% of the city’s power is now carbon-free. That was one of the reasons the Massachusetts Green High Performance Computing Center chose Holyoke, and green energy continues to be a draw for other forward-looking businesses, Lavelle said.

“It has a bit of an economic-development advantage to it,” he told BusinessWest, adding that solar projects are natural fits for properties that aren’t otherwise easily developable, due to wetlands, soil contamination, or some other reason. “It’s revenue the city would not otherwise get. The city’s not getting rich off this, but it’s found money, and certainly helps the revenue side of the ledger that’s always struggling.”

For this issue, BusinessWest explores the benefits that communities glean from solar projects — which helps explain why they continue popping up all over the region.

Positive Outcomes

Like Holyoke, Westfield struck a PILOT agreement with Con Edison on the panels themselves — $10,000 for the first 10 years and $26,000 for the next 10 — while taxing the real estate normally.

“The city still taxes the dirt the same, but with the solar panels on the project, instead of taxing it as personal property, there’s an agreement to fix the price,” Mitchell said. “That’s beneficial to the solar company; they know what they’re on the hook for, and the same goes for the city.”

All parties gave something to make the deal work, he added. “Westfield took a little reduction in the first 10 years of the PILOT, the property owner’s rent was a little less, and Con Edison invested, coordinating with DEP to do all the engineering and pulverizing the materials and spreading it throughout the site. It was an investment on all three players’ part to make this work. Everyone contributed something in order to have a very positive outcome.”

The new array comes on the heels of the Twiss Street solar project built two years ago by Citizen Energy Corp. on a capped landfill that previously generated zero revenue for the city. Now, Westfield taxes Citizen for the property, has a PILOT agreement for the panels, and no longer has to pay to maintain the landfill.

Other communities across Western Mass. have recognized the benefits of solar as well, including, but certainly not limited to the following:

• Greenfield forged an agreement with SunEdison in 2012 on a solar array atop a capped landfill near Route 2;

• The same year, Easthampton opened an array atop yet another landfill on Oliver Street, installed by Borrego Solar Systems Inc.;

• Northampton selected Ameresco Inc. last year to develop a solar array on its former Glendale Road landfill;

• Deerfield struck a deal this year with Lake Street Development Partners on a solar project on River Road;

• Chicopee negotiated with Southern Sky Renewable Energy to create an array this year atop its capped Burnett Road landfill; and

• Wilbraham opened an array near its former landfill earlier this year, developed by Altus Power America.

Springfield spearheaded the current rush of solar arrays with its project atop a former landfill on Cottage Street, developed several years ago by Eversource.

“Not only is it a great source of green power, which communities are attracted to, but for us, it was great from a real-estate-tax point of view,” said Kevin Kennedy, the city’s chief economic officer, noting the financial benefit of placing an unusable parcel on the tax rolls.

Array of Options

Large-scale municipal projects aren’t the only way the state is encouraging people to go green. The Solarize Mass program, maintained by the state Department of Energy Resources (DOER), encourages towns to install solar on a residence-by-residence basis, using one installer chosen by the community.

“The theory is that the cost of installation goes down the more people sign up — essentially the Agway model,” said Rick Sullivan, president of the Western Mass. Economic Development Council and former state secretary of Energy and Environmental Affairs. “The more people buy in, the cheaper it is. If you can get more people to join, your costs go down. So you try to get my neighbors to join as well. It’s been pretty successful around here.”

During Sullivan’s tenure as secretary, his department rewrote the state incentives regarding solar projects to discourage them on agricultural lands and open space, and increase the incentives for smaller businesses, residences, and anything on municipal buildings, landfills, and contaminated sites. “We tried to drive the installations to go into a certain place and not others. It doesn’t preclude agricultural installations, but the incentives aren’t as great.”

The department also began to encourage a program called community solar, by which someone without the ability to install solar power in their own home may purchase a share in another installation. Whatever the case, he said, homeowners who have tapped into solar power see financial benefits once they’re past the initial expense.

“If you own your own power, if you are able to net meter into the grid, you actually, at some points of the year, may be selling power into the grid,” he told BusinessWest. “Therefore, at minimum, you’re reducing your power costs, and you might even be ahead of the game a little bit.”

Meanwhile, larger-scale projects continue apace, from arrays built by large companies like MassMutual and Big Y to the developments on municipal landfills and other difficult sites.

The contracts between developers and municipalies are all different, Sullivan said, but communities must answer some basic questions: do they have the ability to buy power at a reduced rate? Does the community take on some kind of PILOT agreement? Does the community end up owning the facility after some period of time, typically 20 years?

“These are the three buckets: reduced costs, taxes, and what happens to the facility in terms if long-term ownership,” he said. “That’s all a negotiation.”

What these projects don’t do is create many long-term jobs outside of sales and, perhaps, maintenance. But the environmental benefits are very clear, Sullivan said, and so are the tax benefits.

Before this year, we had six megawatts of solar over three major projects,” HGE’s Lavelle said. “This year alone, we’ve added 10 additional megawatts, the Mt. Tom site being the largest of the projects. At the end of the year, we’ll have 16 megawatts installed.”

The Paper City is far from alone in that endeavor, as the race to build solar arrays across Western Mass., well, heats up.

Joseph Bednar can be reached at [email protected]