Explosion of Potential

Springfield Unveils Blueprint for Downtown Innovation District

From the wreckage of a natural-gas explosion in Springfield almost two years ago has emerged a revitalization plan — one that encompasses far more than the immediate blast zone.

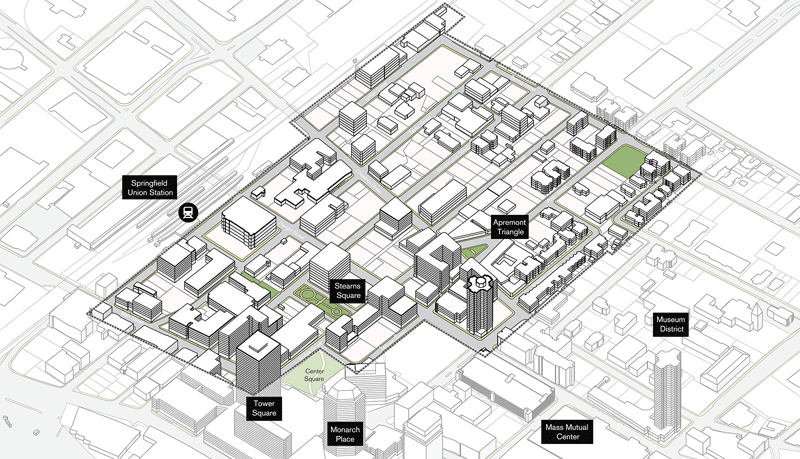

The “Worthington Street District Plan,” as the plan’s creators title it, contains an overarching vision of transforming much of downtown Springfield into an ‘innovation district,’ characterized by entrepreneurial businesses, expanded market-rate housing, new dining and entertainment options, and a raft of infrastructure and traffic-flow improvements.

It is, in a word, ambitious, said Kevin Hively of Ninigret Partners of Rhode Island, which produced the study in conjunction with Utile Inc. of Boston. The firms were hired by DevelopSpringfield, using part of an $850,000 settlement between the city and Columbia Gas stemming from the natural-gas explosion that rocked the Worthington Street-Chestnut Street area the day after Thanksgiving in 2012.

“We want to create an innovation district with a lot of energy and momentum taking place, but the fact of the matter is, innovation districts are driven by talent, and talent is driven by job opportunities and quality of life,” Hively told an assembly of municipal and economic-development officials and other neighborhood stakeholders.

“We want to create an innovation district with a lot of energy and momentum taking place, but the fact of the matter is, innovation districts are driven by talent, and talent is driven by job opportunities and quality of life,” Hively told an assembly of municipal and economic-development officials and other neighborhood stakeholders.

“If you’re going to have an innovation district, you have to create a strong, robust, urban lifestyle environment,” he added. “The reality is, they are related.”

A key example is Kendall Square in Cambridge, which boasts, by far, the nation’s highest density of biotech and IT firms — 163 per square mile, to be precise. (Palo Alto, Calif. comes in a distant second, with 36.) Yet, Kendall Square developers have also been focused on quality of life, as evidenced by the emergence of outdoor cafés, charging stations for electronic devices, and lively kayak and canoe activity along the Charles River.

To develop such an environment in Springfield, the report notes, Worthington Street and its environs is the best place to start.

The key is the neighborhood’s pre-existing assets, including the architectural character of the building stock, public ownership of a number of parking lots and other empty parcels, existing housing stock that can be upgraded, proximity to Union Station, and pre-existing places — like Stearns Square, Apremont Triangle, and Matoon Street — that can serve as anchors for activity.

Once demand for an urban lifestyle — and development in response to that demand — lift the profile of this neighborhood, businesses will hopefully become interested in the neighborhoods northeast of Chestnut Street, producing a cascade effect of development, public improvement, and general buzz across the entire district.

Mayor Domenic Sarno noted that the plan isn’t unlike the city’s efforts over the past three years to bring large-scale improvements to Springfield in the wake of the June 2011 tornado. “From a potentially devastating tragedy, an opportunity has come forth,” he said. “As we did with the tornado, we have an opportunity to define this area as an innovation district.”

Jay Minkarah, president and CEO of DevelopSpringfield, said his organization commissioned the study to establish a vision for how the downtown area should be developed. “We have a tremendous opportunity to create a truly vibrant, urban district, one that is walkable, with an innovation-based economy and market-rate housing — those are exactly the things we’d like to do.”

After all, Sarno added, “if we want to move the city forward, we have to be bold and innovative.”

Food for Thought

As one example, Sarno emphasized repositioning the city’s entertainment district as a restaurant district, because a neighborhood known for catering solely to large clubs and their patrons detracts from its universal appeal.

The Utile/Ninigret report highlighted several ways this can be accomplished, including placing size limits on venues to discourage large clubs; requiring all venues to have full kitchens; and using façade-improvement program funds to improve the aesthetic appearance of the district.

Another key is drawing an eclectic mix of retail businesses to the district, a goal, Hively noted, that Springfield officials can’t just wish into reality.

“It’s very hard to create a successful retail business,” he noted. “It’s out of the hands of the city. It cannot create a successful retail business, but it can create an environment that allows people to come in; then it’s up to the retailers to get people to come in and convert those people from shoppers to buyers.”

But downtown revitalization is about more than making it a destination for diners and shoppers; attracting people to live there is equally important, which is why the city is also looking at ways to develop more market-rate housing downtown. Officials believe a growing network of young entrepreneurs and residents want to see downtown become more livable, and that future rail service to the area will bring new opportunities, both to attract residents and encourage further development around Union Station.

It may sound a dizzying exercise in chickens and eggs, but the report highlights several improvements Springfield can undertake to make the district more attractive for both walkers and motorists. These include upgrading Stearns Square; redesigning Apremont Triangle’s open space and streetscape; converting Dwight and Chestnut streets to two-way streets; restriping travel lanes on cross streets; retrofitting Worthington and Bridge streets; improving Lyman Street, especially at the entrance to Union Station; and incorporating public art and lighting into underpasses.

This stretch of Worthington Street, which includes the site of the natural-gas blast, is among the areas the city hopes to revitalize as part of a broad innovation district.

“Everyone in the world wants an innovation district, but not everyone can have one,” Hively said, adding that the key questions are, does it have to be created from scratch, and are there people willing to make it happen? Clearly, he added, the answers in Springfield are no and yes, respectively. “You don’t have to create this from whole cloth.”

Added Sarno, “we are thinking big, thinking bold, thinking innovative. But the bones are already here, where other cities are sinking millions of dollars into that.”

Still, while those foundational elements exist, the study notes, they are still nascent and the lack critical mass necessary to have a major impact — yet. Other efforts are necessary, among them the potential conversion of the Willys-Overland Building on Worthington Street, which was damaged in the explosion, into a catalytic project featuring a mix of business uses, small-scale manufacturing, and housing.

Sarno said he envisions a neighborhood of revitalized properties featuring retail, dining, and business on ground level, parking on the second floor, and market-rate housing on the third. “It is extremely important that we continue to make downtown Springfield vibrant.”

Safety First

Kevin Kennedy, Springfield’s chief development officer, said the study is valuable in the way it outlines development concepts and encourages residents and businesses to generate more. “For some ideas, the city would have to help with some infrastructure, and that’s what we would do.”

The city has also been focused on public safety and raising people’s confidence in walking downtown — efforts that include everything from a lighting-improvement project along some of the city’s main thoroughfares, including the downtown club district, to police strategies to more effectively patrol the area. Public perception of crime and safety, after all, are “the 900-pound gorilla in the room,” said the mayor.

However, Evan Plotkin, president of NAI Plotkin, told Sarno and others gathered at the study presentation that the best way to make the innovation district safe is to make it vibrant. “Bringing foot traffic to these neighborhoods will do more to create a sense of safety than anything else you can do,” he said. “Having a police plan will augment that, but there’s nothing better for public safety than foot traffic.”

As for the Utile/Ninigret report, Plotkin said he hopes the city moves forward with some of the ambitious plans, and that the study doesn’t just sit on a shelf. “I think we can get it done.”

He’s not alone, judging by the sentiment of Herbie Flores, executive director of the New England Farmworkers’ Council and, like Plotkin, someone invested in the future of Springfield’s downtown.

“There are always going to be negative people in Springfield,” Flores told Sarno at the end of the presentation. “The hell with them. We’re behind you.”

Joseph Bednar can be reached at [email protected]