A Matter of Speculation

‘What happens now?’

‘What happens now?’

That’s the question that was on the minds of many as Hampshire Mall was sold at a foreclosure auction last month — to the company that holds the mortgage on the property, and for far less than half its assessed value.

Actually, people have been asking that question for a while now, as the fate of the mall becomes less clear after years of struggle, even after its former owner, Pyramid Management Group (which also owns Holyoke Mall), started doing the things malls are supposed to do in these changing times, especially shifting gears and devoting far more square footage to entertainment-related venues — everything from a large gym to escape rooms to taekwondo.

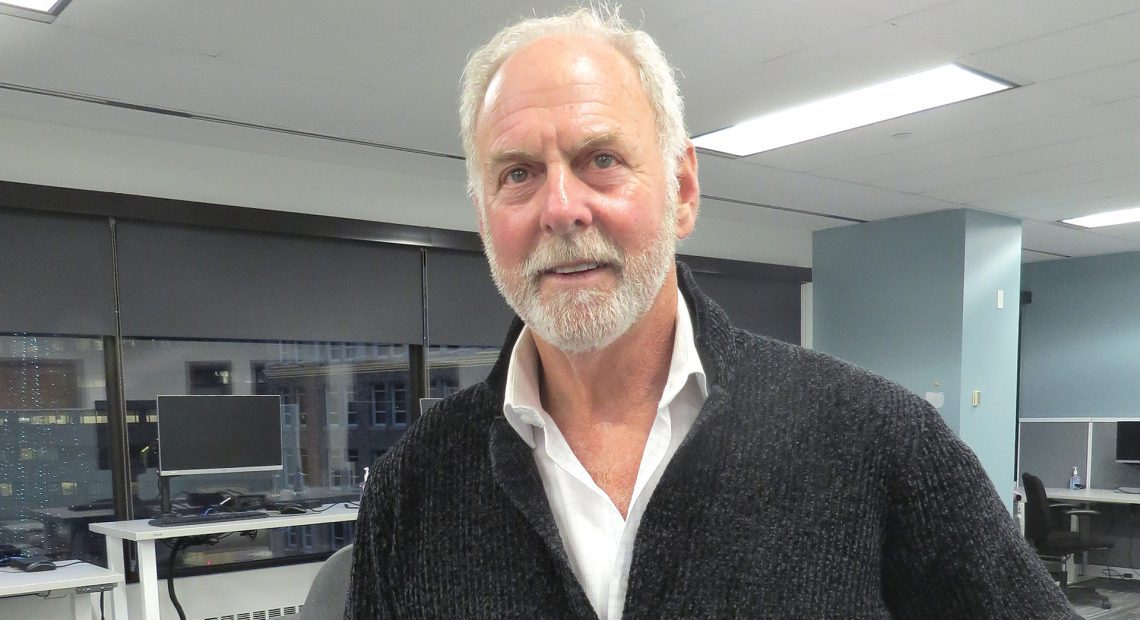

Apparently, all that simply wasn’t enough, said John Benoit, a principal (with his two brothers) of Vantage Point Retail in Longmeadow, which leases and sells retail properties and finds locations for a few national chains, such as Five Guys, Advance Auto Parts, and 99 Restaurant.

“Zoning is complicated, to say the least, and sometimes, when people hear about an effort and there’s a lack of specificity surrounding it, they can draw conclusions that are not appropriate.”

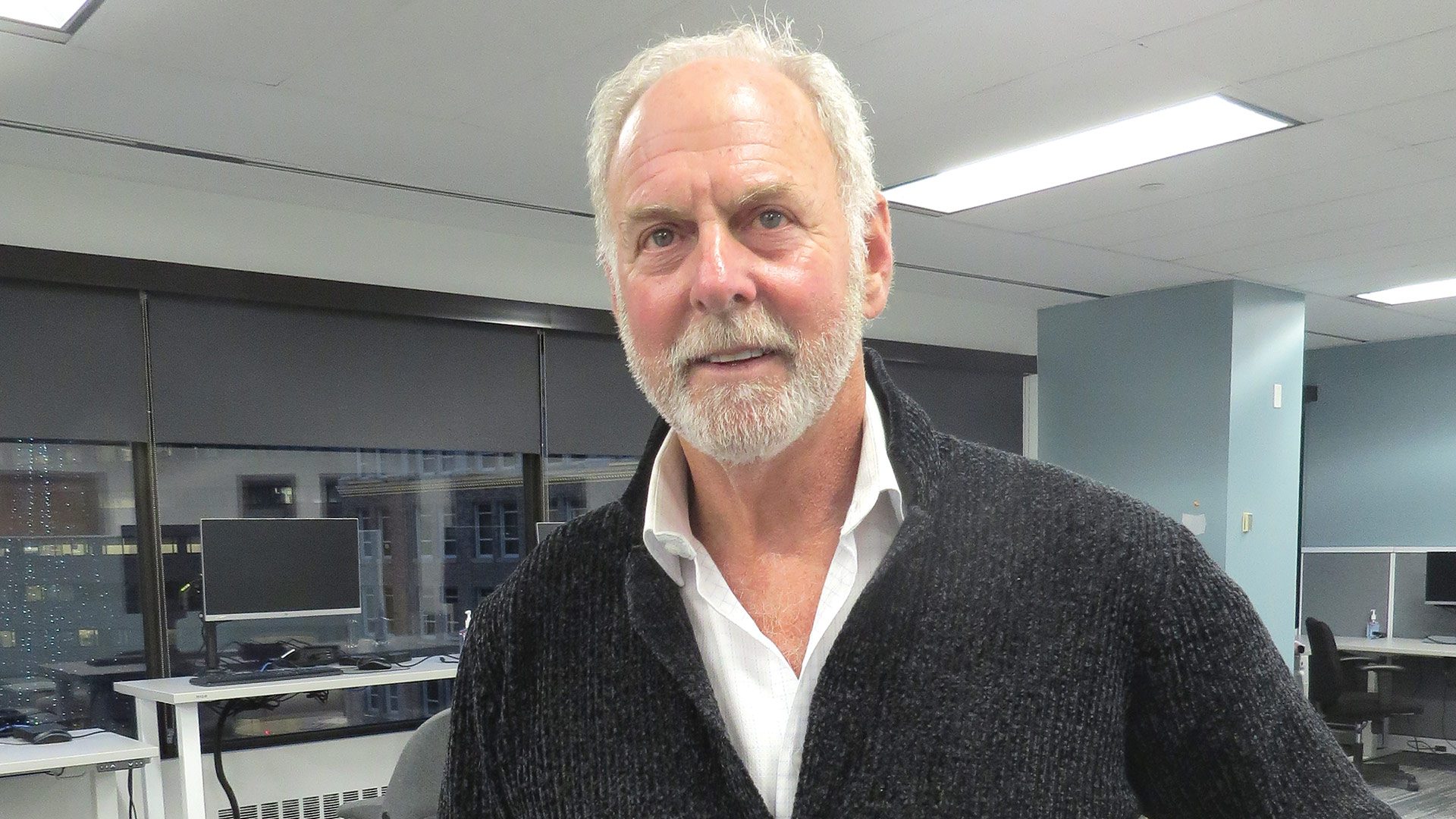

He noted that Hampshire Mall, located near the Amherst line in Hadley on busy Route 9, is just one of many malls across the U.S. that are suffering and destined for new life; others in this region include Eastfield Mall, which has already been demolished, to be replaced by a large power center, and Enfield Square, which is also awaiting its fate. Meanwhile, the retail sector itself is a state of flux.

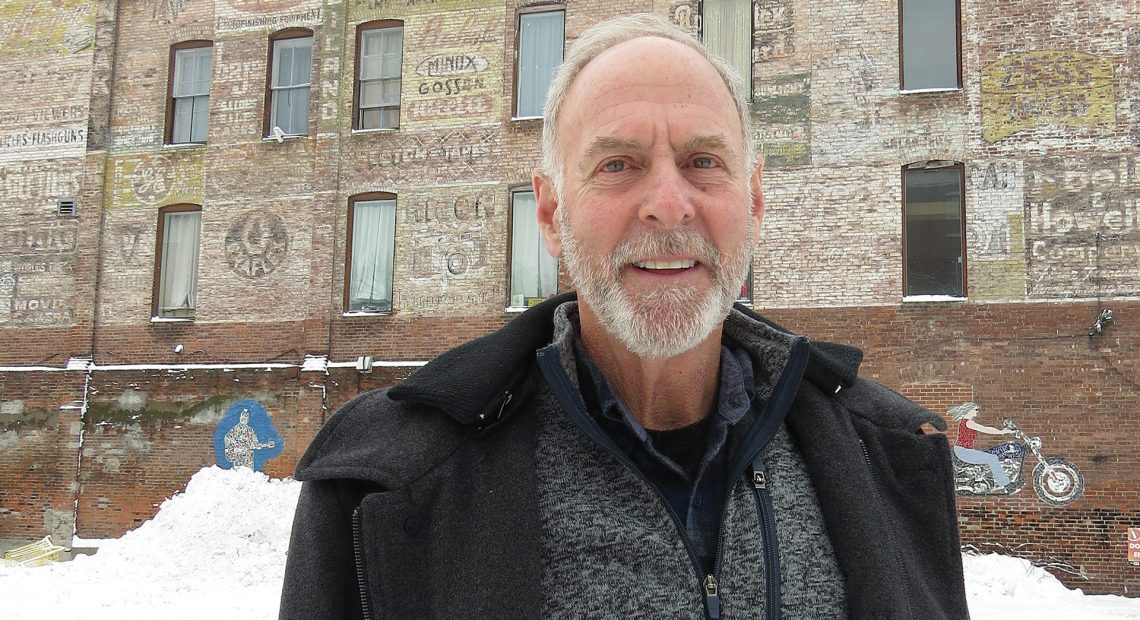

John Benoit says Route 9 is a retail destination, but he wonders how much more retail can come to that busy thoroughfare.

“Retail has been undergoing change for a long time, and I don’t know if it’s settled,” Benoit told BusinessWest. “There was a time when online was a new world in retail and the discussion in the trade journals and at the trade association meetings going back 10 to 15 years was about whether brick-and-mortar locations would go away — would people just do business online?”

What has emerged, he went on, is the concept of multi-channel retail that includes online as well as bricks-and-mortar elements, with some consumers using one or the other for research, buying, returns, or some combination of the above.

“It changes every year,” he added. “Some of the statements I just made … I don’t even know if they’re current.”

Nothing is expected to happen at Hampshire Mall for a while, as the new owner, Deutsche Bank Trust Co. Americas and Wells Fargo Commercial Mortgage Securities Inc., which, as noted, held the mortgage on the property, figures out what it wants to do. The bank foreclosed on the mall after Pyramid defaulted on its mortgage.

Shardool Parmar, a more-than-interested observer at the auction — that’s because the Pioneer Valley Hotel Group, which he serves as president, owns three hotels on Route 9 in Hadley and is building a fourth — said it will likely be years before the fate of the property is known.

“It’s a big unknown what will happen to the mall property,” he said. “That’s because it’s difficult to say what the future market will be when it comes to whether this will remain retail or become residential. There are a lot of unknowns.”

The most obvious future uses are more (and perhaps different) retail — because of the emergence of the Route 9 retail corridor as one of the strongest, if not the strongest, in the region, rivaled perhaps only by Memorial Drive in Chicopee, said Benoit — and housing, mostly because of the size of the parcel and the huge need for more housing in that region.

But both of those options come with question marks. Indeed, while Route 9 is a retail hub, there are vacancies — actually, several of them — along that corridor, Parmar said. Meanwhile, Benoit added, while successful retail and especially grocery stores (and there are lot of them on this corridor) attract more retail, most of the major players, from Walmart to Home Depot, are already there.

“They did what people said what malls could do and should do, and they did it early — and that’s entertainment, as compared to shopping. They had the shopping, but they also had an entertainment component.”

As for housing, a zone change would be required, said Hadley Select Board member Molly Keegan, noting that the town will likely pursue creation of what’s known as a 40R, otherwise known as a smart growth zoning overlay district, which, according to the state’s website, “seeks to substantially increase the supply of housing, and decrease its cost, by increasing the amount of land zoned for dense housing.”

“The Planning Board has been working with the Pioneer Valley Planning Commission on researching and potentially bringing a zoning change to town meeting in either the spring or fall of 2025 that would allow for additional types of development, specifically using Chapter 40R,” Keegan explained, noting that the intent of 40R is to encourage municipalities to create dense housing or mixed-use zoning districts.

Such a proposal would require educating town residents about just what such a zone is for and what could happen if one becomes reality on that corridor, she noted, adding that, if a vote comes to fruition, it will Hadley’s first attempt at creating a 40R.

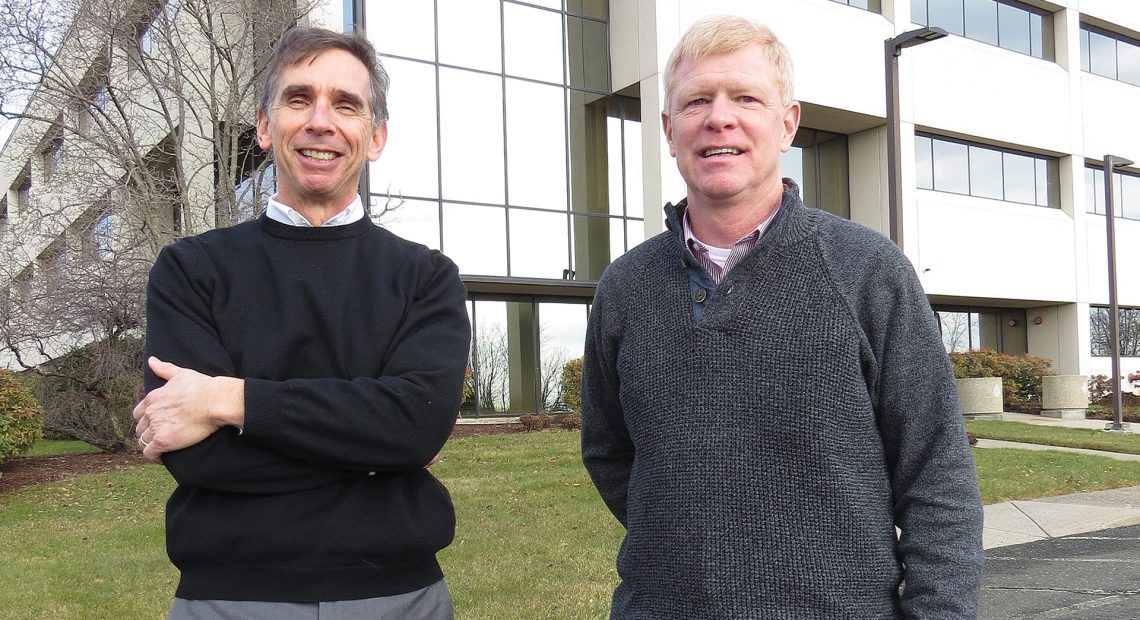

Molly Keegan says information and education will be the keys to passing a needed zone change to permit dense housing at the Hampshire Mall site.

“There’s an awful lot of education that needs to go along with this,” Keegan said. “Zoning is complicated, to say the least, and sometimes, when people hear about an effort and there’s a lack of specificity surrounding it, they can draw conclusions that are not appropriate. So the most important thing the town can do right now is educate.”

For this issue and its focus on commercial real estate, we take an in-depth look at Hampshire Mall and what might come next for this retail and cultural landmark.

Landmark Decisions

Hampshire Mall is one of the several area spots that gets some exposure in the recently released Janet Planet, a coming-of-age movie set in Western Mass. in the early ’90s.

In a recent Boston Globe article intended to help readers understand just what ‘Western Mass.’ is — and how the movie helps explain that geography — it is noted that the mall became a solid locale for the movie because … well, with a JCPenney and a rollerskating rink, it looks the part of an early-’90s mall.

In the larger scheme of things, that’s probably not a good look, even though, as noted earlier, the mall has made some significant changes in recent years to make it more viable, especially that shift to more entertainment-related venues. Indeed, in most respects, it doesn’t look like an early-’90s mall, with tenants that include FunHub Action Park, All In Adventures, LaserBlast Ancient Adventure, Planet Fitness, and PiNZ, a bowling alley.

“They did what people said what malls could do and should do, and they did it early — and that’s entertainment, as compared to shopping,” he explained. “They had the shopping, but they also had an entertainment component.”

This shift helped, but it certainly hasn’t stemmed the mall’s decline, said Benoit, theorizing that habits changed during the pandemic — people didn’t want to be indoors around a lot of other people — and they haven’t really changed back.

This reality, coupled with the many changes in retail — and the proliferation of other retail on Route 9 — conspired to all but seal the fate of Hampshire Mall, he noted, adding that similar stories have been written at malls around the country. The ones changing the narrative for the better have embraced reinvention.

“Malls are really struggling, and that struggle didn’t just start — it’s been going on a long time,” Benoit said, emphasizing that word ‘long.’ “Malls are big, complicated financial and physical arrangements.”

Using Eastfield as an example, he said talks about converting it to a large power center with a housing component have been going on for at least 15 years, by his count. Advancing those plans have been complicated by everything from the Great Recession to the pandemic; from ownership of some footprints by the anchors themselves, which slows and adds more layers of complexity to the equation, to the fate of existing tenants.

“The more information people have, and the earlier they have it and have time to ask questions and digest it, the better they’ll understand what they’re voting on what they get to town meeting.”

That question of what might come next at Hampshire became an assignment — “Reimagining the Hampshire Mall: Exploring Opportunities for Intergenerational Housing and Community Development” — for 40 juniors in the architecture and landscape architecture programs at UMass Amherst.

Teams of five students presented different concepts for the mall property. Each one included 350 to 700 new housing units, designed for young professionals, working families, and seniors; site amenities for residents and visitors; parking for tenants and shoppers alike; and some portions of the existing mall. Many of those elements are likely to be included in whatever the mall becomes next, said those we spoke with.

Getting back to a possible 40R zone at the Hampshire Mall site, Keegan said the Planning Board has formed a smart-growth subcommitee that is specifically working on the next steps in the process of creating such a zone. Informational sessions will be scheduled to help inform the public of what is involved and what it means for the community moving forward.

“The more information people have, and the earlier they have it and have time to ask questions and digest it, the better they’ll understand what they’re voting on what they get to town meeting,” she added, noting that, while there is a recognized need for more housing in the community, 40R and its emphasis on dense housing is a new concept for Hadley.

What certainly isn’t a new concept is retail on Route 9. With five colleges only a few miles away and several smaller communities without their own retail centers, the stretch between the Coolidge Bridge and the center of Amherst has been a retail destination for more than 50 years now, one that has consistently added new regional and national brands to the portfolio, becoming what Benoit called a ‘super-regional trade area.’

As a measuring stick, he pointed to all those aforementioned supermarkets. As he commenced counting them, he started with Big Y and Stop & Shop and ended with Maple Farms, a smaller, independent outlet, and listed eight in all. And he was quite sure there was a ninth that he couldn’t recall.

In any case, all those supermarkets attract other retail, he said, adding that there may still be room for more on Route 9, including at a reshaped Hampshire Mall property, where a power center, at which “every store has a front door,” as he put it, could — that’s could — be part of the equation.

History Repeats?

That’s what happened at Mountain Farms Mall, which opened in 1973 and, ironically enough, became known as the ‘dead mall’ after its precipitous decline and the closing of all but a few of its 35 stores.

Converted to an open-air mall and anchored by Whole Foods Market and Walmart, it is now thriving — so much so that Benoit wondered out loud if there is, in fact, room for more retail on that stretch.

“I’m not sure retail is that strong anymore,” he said. “And with the Mountain Farms Mall thriving, a lot of tenants that are in business are already in that market. Between there and the Stop & Shop center, there’s already a lot of retail. The anchors are there — Home Depot, Lowe’s … there’s no one left.”

Parmar concurred, noting that, whatever comes of the site, it will be costly and probably complex.

“There are a lot of variables, including the cost of construction,” he told BusinessWest. “To bring something to light there is not going to be cheap, and will there be a return on investment? There is a lot to investigate before someone can say ‘this will work’ or ‘that will work.’”

“This will require multiple sources — you don’t just make one or two phone calls and someone says, ‘yeah, I like that project; I’ll fund it with you. It’s going to take more than a village — it’s going to take a little city.’”

“This will require multiple sources — you don’t just make one or two phone calls and someone says, ‘yeah, I like that project; I’ll fund it with you. It’s going to take more than a village — it’s going to take a little city.’”