A Changed Landscape

Nonprofit Managers Face a Host of New Questions — and Challenges

Sarah Tsitso has been spending a lot of her recent spare time on eBay, looking for 1920s garb.She needs a dress and some accessories for a Nov. 17 fund-raiser at the Museum of Springfield History that she has created for the Boys & Girls Club Family Center, which she serves as executive director. It’s called ‘Jazz Fantasia,’ billed as an opportunity to experience the so-called Harlem Renaissance (which Tsitso has studied extensively) with jazz music, dinner, and both live and silent auctions.

“It’s something really different — which you definitely need these days,” said Tsitso, adding that, when it comes to raising funds for the family center (or any nonprofit, for that matter), a large dose of imagination and a willingness to look well beyond the traditional golf tournament or the usual event venues are certainly necessary.

And that’s just one of the many ways in which the lives of nonprofit managers have changed in recent years, she told BusinessWest. New challenges range from heightened competition for available funds to a need for far greater accountability when it comes to how funds are expended; from a critical need to create partnerships and collaborations with a host of constituencies to simply securing the operational funding to keep the lights on.

“The new buzzword is ‘measurable outcomes,’” she said, adding that most all donors are seeking (or demanding) them these days.

Kirk Smith, executive director of the YMCA of Greater Springfield, agreed, and used the phrase “new questions” to describe what nonprofit managers are facing these days, adding quickly that, to succeed, they need thoughtful, specific, and effective answers.

“Before, you could put together a good mission statement, and people would give you money based on just that — but those days are long gone,” he explained. “Now, what they want to know is your track record — how have you demonstrated that what you’re doing is effective?

In this new environment for nonprofits, Kirk Smith says, organizations and their leaders must do many things well, but above all else, they must be able to effectively communicate.

These are questions that nonprofits are not used to answering and didn’t have to answer until maybe a decade or so ago, he continued, adding that, overall, this responsibility is a good thing for all parties involved, because greater accountability helps an organization stay on mission, and statistical evidence of success is far more effective than anecdotal evidence when it comes to gaining additional support.

To succeed in this changed environment, organizations and their leaders must do many things well, said Smith, adding that, above all else, they must be able to effectively communicate. And there is much that goes into this, he went on, adding that it means everything from relaying an organization’s mission to conveying how well it is meeting stated goals, to sustaining a dialogue with funders about what they see as priorities and would like to accomplish.

“Today, it’s not about asking for money, but asking for a conversation,” he said. “Donors are not just people who give you money; you have to understand them and tap into what’s important to them, not what’s important to you.”

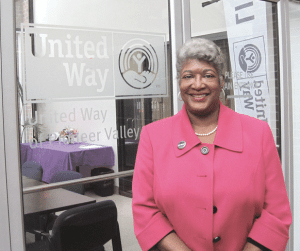

Summing it all up, Dora Robinson, executive director of the United Way of Pioneer Valley, said today’s nonprofit managers must wear many hats, and, in a word, be “generalists.” Elaborating, she said, while they still must be devoted to the mission — that part won’t change — they must also develop new programs, be well-versed in financial matters, be effective managers of employers and groomers of talent, and, overall, be visionaries.

“People have to manage from soup to nuts,” she explained, “ and it’s a real challenge keeping all those balls in the air while at the same time looking for new opportunities. Now, you have to be a solid fiscal manager; the new leadership requirements for nonprofits are to not only be a good friend- and fund-raiser, but also a good manager.”

The phrase ‘operate like a business’ is overused and somewhat of a cliché when it comes to nonprofit management, said Andrew Morehouse, executive director of the Food bank of Western Massachusetts, but it’s quite accurate.

A recent graduate of the MBA program at the Isenberg School of Management, Morehouse said nonprofit managers today must be adept in everything from strategic planning to teamwork building to Stephen Covey’s famous seven habits.

For this issue and its focus on nonprofit management, BusinessWest talked with several administrators about the changed — and still changing — landscape, and what it means for their organizations.

Exercise in Creativity

As she talked with BusinessWest about her organization — which traces its roots back to 1899, when it was a settlement house in Springfield’s North End — and the many challenges involved with nonprofit management, Tsitso took a break for a tour that helped her get several points across.

She pointed out the large kitchen, and, while doing so, talked about how the center doesn’t just feed children, but engages in educational programs about proper nutrition — a reflection of changing times, heightened awareness about the problem of childhood obesity, and a broader mission. And while traversing the hallways, she mentioned her desire for a capital campaign aimed at expanding the nearly 50-year-old Acorn Street facilities.

The highlight, though, was a new outdoor play center that was almost ready for prime time. An addition to the offerings at the family center, the facility was created in response to several recognized needs and goals — especially a desire to provide outdoor recreation to children who have limited access to both playground equipment and fresh air.

“My daughter goes to Springfield public schools, so I know first-hand how little time they get outside,” Tsitso noted. “Recess is nothing — if they get it at all, it’s 10 minutes, and there’s very little playground equipment. And most of the children in this neighborhood live in apartments, and oftentimes, it’s not safe to walk around.”

So she applied for a grant through the Boston-based Amelia Peabody Foundation to build a playground, and she admits that this was somewhat of a hard sell.

“It was a tough one, because they don’t typically fund playgrounds, and they weren’t interested in funding this one,” she recalled. “But the pitch I made to them was about childhood obesity and diabetes, and the fact that we need to provide opportunities to keep children active in any way we can. I convinced them that this was important.”

Together, Tsitso’s commitment to creating an outdoor play area and her success in securing the funds to get it done reflect many of the challenges facing nonprofit managers today — everything from the need to be creative and persistent in the pursuit of funds to fully knowing and understanding what drives those who eventually open their checkbooks.

“Years ago, many of the managers of nonprofits were former corporate executives,” said Tsitso as she attempted to sum up the new environment. “They would go to their corporate contacts and very passionately pitch the cause … and people would just start writing checks.

“It worked — for that time and that purpose — but it doesn’t work anymore,” she continued. “I can’t just waltz into MassMutual and ask them to cut me a check for a $1 million. That’s not going to work; I wish it would, but it won’t. You really need to spend time and steward donors and figure out how your mission and what you’re trying to accomplish falls in with that corporation and the goals that they’ve set for themselves.

“It’s all about finding that symmetry between nonprofit and business,” she went on. “What businesses really want to support at-risk youth in our community? Some are very interested in the arts, some are into cancer research; you have to find the right match for you.”

Using different words and phrases, Smith said essentially the same thing, putting heavy stress on the need for nonprofits large and small to be accountable, while also providing something else for donors: bang for their buck.

“Donors want to understand how their support is making an impact,” he told BusinessWest, adding that, to help in this process, nonprofits must provide more quantitative (rather than qualitative) evidence than ever before, meaning those measurable outcomes. “Accountability is much greater — there’s no more ‘here’s $10,000, go help some kids.’ The conversations have to be at a much higher level than that, and I think that’s appropriate.

“Charitable giving is up in America,” he continued. “But it’s more competitive in terms of fund-raising, and you need to be prepared to be held accountable, moreso than you did in the past.”

By the Numbers

As an example, he pointed to the Y-AIM Program, which matches at-risk teenagers with mentors, with the goal of keeping them in school and seeing them through to graduation. The initiative was created with the initial support of Big Y, and First Niagara and Health New England have been more recent backers, said Smith, noting that all those involved have been looking for evidence that it’s working.

“People need to see some specific numbers,” he said, adding that, with Y-AIM, there are some.

“This program is about addressing at-risk high-school students who have very low GPAs, are repeaters, and have low attendance and behavior problems,” Smith explained. “We started at Sci-Tech [the High School of Science and Technology] with 40 kids, and we graduated 39 of them; 36 went to college, one went into the military, and one went into the Job Corps.”

With those numbers in hand, program administrators have been able to gain the attention and support of other donors, said Smith, adding that Y-AIM has expended from one school to three and now four. “If we weren’t able to demonstrate success and track the data, we wouldn’t be where we are now.”

But quantifying results is often difficult for smaller nonprofits, said Tsitso, and especially with her organization, where the goal is often prevention.

“It’s harder to measure the ‘don’ts’ than the ‘dos,’” she explained. “Our outcomes are really non-outcomes; we start with a child who’s 6 or 7 years old, and through the services we provide, they don’t get pregnant at 14, they don’t join a gang, they don’t drop out of high school, they don’t engage in risky behavior, and they don’t end up in jail.

“We can measure our children, but it’s a long-term measurement,” she continued. “We’re talking about a 6- or 7-year-old; let’s see where they are at 20. It’s not something we can measure on a one-year grant cycle.”

Beyond this dilemma, however, the advent of greater accountability has brought other challenges for nonprofits, said Robinson. Elaborating, she said that, in this changed environment and its greater emphasis on programming and measurable outcomes — what she called “moving the needle” — basic operating costs often get overlooked.

“One of the big questions today for organizations like the United Way is, how do we keep the infrastructure in place to really support and promote our mission and our work?” she explained. “You need to have an administrative infrastructure in order to do the kind of work that needs to be done in communities — so who pays for that?”

This challenge is compounded by unfunded mandates at both the state and federal level, she said, as well as by new reporting requirements dictating that work be done electronically, which constitutes a major burden for many smaller agencies.

“Some can’t meet these costs,” she told BusinessWest, “and while some can, often they do it at the expense of direct services.”

And this brings her back to that notion about nonprofit managers being generalists and keeping a large number of balls in the air at the same time, especially when so much emphasis is on programs and quantifying the results they’re generating.

“The funders want to provide funds for the programs, but not necessarily the operations,” she explained. “And that makes it almost impossible for some nonprofits; those organizations then have the additional burden of doing fund-raising. Not only are they trying to manage and bring in resources through contracts from state and federal foundations, they now have to do fund-raising to cover the gaps.”

Meanwhile, they have to be able to attract and effectively manage talent and get a team to move in the same direction, she went on, adding that, for many, this requires additional education, such as an MBA, or work in college programs specifically tailored for nonprofit managers (see related story, page 22).

Getting the Mission Accomplished

While acknowledging that some things have indeed changed for nonprofits, Morehouse said many aspects of effective management in this realm have simply been “rediscovered.”

At the top of that list, he told BusinessWest, is that all-important element of trust, and the need to establish and maintain it with all constituencies, including the many different funders of the organization, from corporations, individuals, and foundations to state and federal government.

“There are certain basic elements of humanity that make social enterprises work, whether be it a for-profit business or a nonprofit business,” he explained. “We’re social enterprises where human beings have to interact to create a product or service to get it out the door — and trust is a very important element.

“Employees want to be able to trust one another; partners in a business relationship want to be able to trust one another,” Morehouse continued. “And when you have that trust, respect, and fairness in a relationship, you can create a lot more productivity, whether it be producing a good or providing a service, because people want to do it; they feel good about it and they’ll go the extra mile, not just because they believe in a mission, but because they believe in their peers and their partners.”

Another element that has in many ways been rediscovered, or re-emphasized, he went on, is the need to create and strengthen relationships and partnerships at all levels.

These include the organization’s board, donors, the communities being served, other nonprofits, and especially the internal partners — emergency providers (pantries) that distribute the food to clients. Such relationships help stretch available funding, he explained, while also enabling organizations to take their missions in new directions and become something else that nonprofits must be in this day and age: nimble.

“One of the efforts that we’re undertaking for the next few years is to work with our network of emergency providers to create efficiencies through better collaboration and cooperation, and some of that will result in reducing duplication of effort,” Morehouse said.

Tsitso echoed those comments, noting that the family center has successfully forged partnerships with groups ranging from Link to Libraries to Rick’s Place (which counsels children who are grieving lost parents) to Girl Scouts of America (there’s now a troop at the center) to broaden its mission and better meet it.

“These partnerships are allowing us to do a lot more with less,” she explained. “They allow us to offer far more than homework help and free gym time; we can really put together a slate of programs that kids enjoy.

“Because these other organizations are willing to work together with us, we’re able to expand our reach, expand our visibility, partner on some grants, and share important information, because we’re serving basically the same population.”

This talk of partnerships and collaboration brings Smith back to his comments about how nonprofits shouldn’t be asking for money these days, but instead asking for conversations. And these talks have changed, he went on, noting that, instead of asking how a corporation or foundation can help the Y, the Y is asking how it can help those entities reach their stated goals.

“First, we explain to them who we are, and detail the depth and breadth of our work,” he said, “and then we ask, ‘what do you want to see addressed in the community?’

“That’s the question we ask funders, whereas in the past, we would say, ‘we have a menu of programs — pick one.’ Now, it’s ‘what do you want to see addressed in the community?’” he continued. “‘Is it education, childhood obesity, teen pregnancy … what needs to be addressed?’ And then we ask them, ‘if we’re able to put something together consistent with meeting that need, will you fund it?’”

Changes of Note

For Jazz Fantasia, Tsitso and her staff at the family center will give the history museum the look and feel of the Roaring ’20s for an event that will be a decidedly different kind of fund-raiser.

For her and other nonprofit managers, though, there is no turning back the clock when it comes to what is expected — and demanded — of them, and the myriad challenges they face.

This is a different era, a time for those new questions, as Smith called them, and for terms such as accountability, measurable outcomes, partnerships, and collaboration.

And they will define the landscape for the foreseeable future.

George O’Brien can be reached at [email protected]