Striking a Chord

Hard Rock Submits a Casino Proposal of Note

Eugene Cassidy had been on the job as president and CEO of the Eastern States Exposition (ESE) for less than a week when officials at the Bronson Companies initiated discussions that eventually led to serious talk about the possibility of locating a casino on the Big E grounds.And it was very soon thereafter that he started canvassing members of his board for their thoughts on that subject. What he found was that, as with the general public in most respects, there was little, if any, middle ground on the matter; some were quite supportive, while others, he said, used direct and sometimes profane language to make it clear that they were not.

“One of them said to me, ‘are you out of your … mind — you’ve only been CEO for a matter of days; do you want to get yourself … fired?” he recalled, deleting the expletives, but adding pauses for effect.

But he said he was able to change such attitudes with what he considers some powerful arguments, presented at subsequent, and very intense, board meetings. The first is that a casino paying a sizable lease to the Big E for the property that would be needed for parking and the assorted facilities would ensure the survival of the century-old institution for the foreseeable future.

The second is that he considers the Big E to be the best steward to operate a casino in the western region of the state.

“The Legislature has said that gaming is now legal in Massachusetts, so now it’s a question of who’s going to be the most responsible party to be involved with this,” he told BusinessWest. “And I could make an argument all day long that this organization is precisely the most responsible host; there’s no one more well-equipped than the Eastern States Exposition, and the town of West Springfield, to handle this.”

It is these arguments, and especially the latter, that Cassidy, who took the reins at the Big E in June, hopes will bring town and area residents, not to mention the Mass. Gaming Commission, around to the idea of embracing Hard Rock Entertainment’s plans to build a $700 million to $800 million resort casino on land at the Big E currently used for parking.

He knows there are questions, and many of them, about parking, traffic, how to juxtapose an immensely for-profit venture with the exposition’s nonprofit status, and many other concerns, and he expects that they will all be effectively answered in the weeks and months to come. For now, though, he’s ecstatic to simply be in a position to have to answer such questions and, as he put it, “have a seat at the table” in the great casino contest.

So is Jim Allen, Hard Rock’s chairman.

For more than a year now, the company has been actively engaged in nailing down a site for a Western Mass. casino, after concluding, as others have, that this area presents the best odds for gaining a foothold in the Bay State. Hard Rock looked at perhaps seven or eight sites in Western Mass., including one in Holyoke and several in downtown Springfield, he said.

It was only after the Bronson Companies, serving as a consultant to several casino entities, engaged Cassidy in those aforementioned discussions that Hard Rock eventually narrowed its search to a 38-acre tract in the southeast corner of the Big E property.

Allen acknowledged that the site has its obvious challenges, especially traffic, but he said all the Western Mass. proposals have challenges, and, in some respects, the Big E site presents fewer than the downtown Springfield locations, while also offering more flexibility with its size.

Ultimately, he believes the plan that emerges, coupled with Hard Rock’s brand and strong track record in both gaming and entertainment — the company has facilities in 58 countries — will enable the project to win over both voters in West Springfield and members of the Gaming Commission.

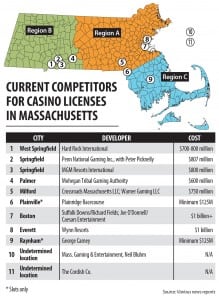

For this, the latest in a series of stories about the contest for the Western Mass. casino license, BusinessWest talked with Cassidy and Allen about what has become the fourth entry in the pitched battle for the Western Mass. casino license, and why they believe they can, and will, triumph in that contest.

Working in Concert

Eugene Cassidy says a casino on the Big E grounds would ensure the long-term survival of the nearly century-old fair.

He told BusinessWest that he pays an annual visit to the Delaware State Fair, which became the site for a casino in the late ’90s, and has made fairly regular trips to the Erie County (New York) State Fair, which added one several years ago. He’s also been to the famous Calgary Stampede, which has long had a gaming facility on its grounds.

In each instance, he said, the revenue gained from leasing land to the casino has become a game changer for the facility in question.

“What the casino does in all those cases is provide the kind of economic support that only an operation of that size and scope can provide,” he explained. “The economic wherewithal of a casino is such that they can afford to really play an active role in the infrastructure of the facility.

“I’ve seen Delaware improve dramatically in just the few short years they’ve had it,” he continued. “And in New York, they’ve done dramatic things to the fairgrounds.”

The Hard Rock proposal has the same potential for the Big E, said Cassidy, noting that the revenue gained from leasing land to the casino operator could be put toward renovating many of the older facilities at the ESE, including the 97-year-old Coliseum.

“We’re trying to struggle along and preserve a 100-year-old facility that has 44 buildings, 31 of which were built before World War II,” he explained. “It’s an incredibly capital-intensive plant; I have an engineering study in my drawer completed in 2008 that shows that to rehabilitate the Coliseum — the gem of the fairgrounds, the jewel in the crown of West Springfield, the place where the American Hockey League was founded — would cost more than $52 million.

“We just had the biggest fair in our history, and we’re going to probably earn, after depreciation, $1.3 million, $2.8 million before depreciation,” he continued. “There’s no possible way that you can capitalize a $52 million rehabilitation, which today is probably $62 million, on $2.8 million before depreciation.”

But generating revenue for capital improvements is merely one of the benefits to be derived from having a casino on the grounds, he went on, putting simple survival at the top of that list.

Indeed, he listed a number of state fairs, including those in Virginia and Michigan, that have gone out of business in recent years due to a combination of declining state support and increased competition for the entertainment dollar from, among other things, casinos.

He said that such a fate is not inconceivable for the Big E, despite its continued success at the gate, and that, at the very least, a casino located across the river in Springfield — and two are proposed for the City of Homes — would negatively impact the ESE in matters ranging from its book of business on conventions, meetings, and traveling shows to its ability to book musical talent, something that’s already impacted by the two casinos in Connecticut.

These were some of the many points he made at an elaborate red-carpet rollout of Hard Rock’s plans at Storrowton Tavern earlier this month. Bret Michaels, from the rock band Poison, was in the house, doing two sets, which included an acoustic version of “Every Rose Has Its Thorn.” Hard Rock also brought along a few of the tens of thousands of pieces of music memorabilia in its vast collection, including a bass guitar used in concert by Gene Simmons of KISS and Michael Jackson’s red leather “Beat It” jacket.

Amid all the hype, music, and visuals was some plain talk, especially from Cassidy, who called the Hard Rock proposal “a once-in-a-lifetime economic-development opportunity.”

How it came into focus is an intriguing example of what some might call trial and error or a process of elimination, but which Allen described as a scientific search for a location that offered accessibility, flexibility, and, in broad terms, the best chance for success in the competition for the casino license.

Like MGM, Penn National, and Ameristar (before it dropped out of the race), Hard Rock was attracted to Springfield because of its location, accessibility, and demographics, said Allen, adding that the company simply wasn’t able to piece together a site that worked in the city.

“We felt that, in downtown Springfield, there were some great opportunities, but we just couldn’t come to grips with land assembly that would give us the appropriate acreage to design something that becomes more than a casino or a slots-in-a-box facility,” he said. “When you’re dealing with a downtown city grid and the restrictions that go with that, we just didn’t feel we could design something that would be beneficial to our brand and beneficial to the citizens who live in that area.

“We felt that, in downtown Springfield, there were some great opportunities, but we just couldn’t come to grips with land assembly that would give us the appropriate acreage to design something that becomes more than a casino or a slots-in-a-box facility,” he said. “When you’re dealing with a downtown city grid and the restrictions that go with that, we just didn’t feel we could design something that would be beneficial to our brand and beneficial to the citizens who live in that area.

“And, frankly, when the opportunity came about to be involved with the Big E, this was truly a marriage made in heaven,” he continued. “With 175 acres, all that history, and the Big E’s focus on entertainment, we thought this was something that would be very positive.”

Ready to Rock

Allen said his company’s proposal, named Hard Rock New England, would feature a 200,000-square-foot casino with 100 to 125 table games and 2,500 to 3,000 slot machines, a 400-room hotel, a spa, a restaurant, shops, a pool area, a concert and show venue, and a permanent music-memorabilia collection.

He told BusinessWest that the proposal reinforces Hard Rock’s reputation for building not just gaming facilities — or “machines in a box,” as he called them — but entertainment complexes.

And this specific model, he believes, will dovetail nicely with the Big E and its brand of family entertainment — complementing it, but not competing with it.

There are obviously concerns about traffic, he noted, adding that he believes a downtown Springfield casino, such as those they considered, would present even more challenges in that realm. “How do you find 3,000, 4,000, or 5,000 parking spaces in downtown Springfield and get the people in and out of there, along with the people going to the central business district?”

In West Springfield, he said the company is looking to work with the community, consulting engineers, and the state to create a comprehensive access plan that addresses both historical traffic problems that have characterized the fair throughout its existence and additional volume from a casino complex.

“We want to be part of the solution, not part of the problem,” he said, acknowledging that his ability to back up those words will go a long way toward determining how the residents of West Springfield may vote on gaming referendum — one of the many hurdles this project will have to clear to become reality.

“This will be a ground-zero, door-to-door approach,” he said. “It starts with the community’s concerns and addressing them in our design thought processes. If one looks at gaming on a national basis, the majority of people now look at it as a form of entertainment that creates a tremendous amount of jobs.

“If we use that as the foundation block,” he continued, “the key for us is to design something that will be an additional attraction to the community and not something that is going to create additional stress on the infrastructure, the police, or the fire department.”

Hard Rock’s plans put the Big E in a much different situation than it was in just a few months ago, said Cassidy, acknowledging that this position — one where the institution is a competitor to other casino operators, rather than an observer or potential collaborator — comes complete with great opportunity, but also sizable risk.

But it’s a position he felt he needed to be in, primarily because he believes he wasn’t getting anywhere in his efforts to gain the attention of casino developers, and was putting his operation in jeopardy by merely taking the role of bystander.

“I was, and I still am, extraordinarily concerned about the ability of this organization to function in the future, because no one is looking out for the Eastern States Exposition,” he explained. “In fact, to the contrary, there are those who feel we don’t do enough or we don’t provide enough, when, in fact, we are the biggest economic cultural event that takes place east of the Mississippi, generating a quarter of a billion in revenues brought into Hampden County in just 17 days.

“Now, the town of West Springfield, rather than bordering a community that’s been incredibly parochial in its discussions about a casino, has a seat at the table,” he continued, adding that it wasn’t until very recently that he believes he heard a Springfield official use the word ‘regional’ when discussing a casino.

“Up until then, it had been all about Springfield,” he went on. “I don’t want to make this a war between Springfield and West Side, but now, the town of West Springfield and the Big E have that seat at the table, and I’m going to be able to provide a means by which this organization can carry on.”

Cassidy told BusinessWest that, in many ways, he regrets the way casinos have almost completely dominated his first six months at the helm. He said that it was his intention upon taking over — something that was planned and scheduled nearly a year earlier — to reaffirm the need for philanthropy to the organization, and to be what he called the “reincarnation” of Joshua Brooks, who founded the fair in 1917.

But in many respects, pursuing a casino is the kind of ambitious, entrepreneurial venture that Brooks would have embraced, he went on.

“Mr. Brooks was an incredibly dynamic thinker and a very progressive man,” said Cassidy. “It’s my goal to see to it that he’s not lost to the history books; as a young man, he was incredibly successful because he was a forward thinker who embraced change. And I have every confidence that Mr. Brooks himself would embrace this change.”

The Big Finale

Cassidy told BusinessWest that, if he had his druthers, he would have had the state Legislature pass a gaming measure similar to the one approved in Indiana.

There, he explained, there is a provision that roughly 6% of the receipts from casino operations sent to the state are routed to the state fair — a windfall he puts at $6 million to $8 million per year.

“If we had that here, we wouldn’t be going through this,” he said with a laugh, referring to the multi-stage “beauty pageant” involving the Western Mass. casino license and the Big E’s presence as one of the contenders.

But the reality is that there is no such provision, so Cassidy is left to work in concert with a casino operator, which eventually became Hard Rock, to secure such revenue in a far different way.

Whether things go as Cassidy and Allen hope remains to be seen, obviously, but it is clear that they intend to make the most of their seats at the casino table.

George O’Brien can be reached at [email protected]