A Tale of Two Cities

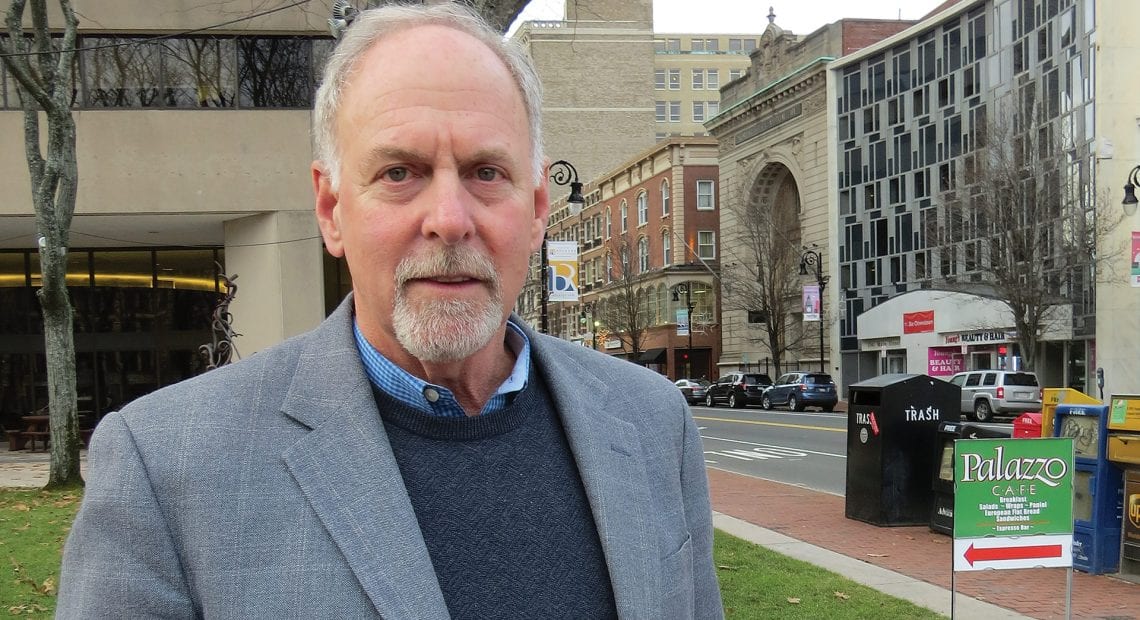

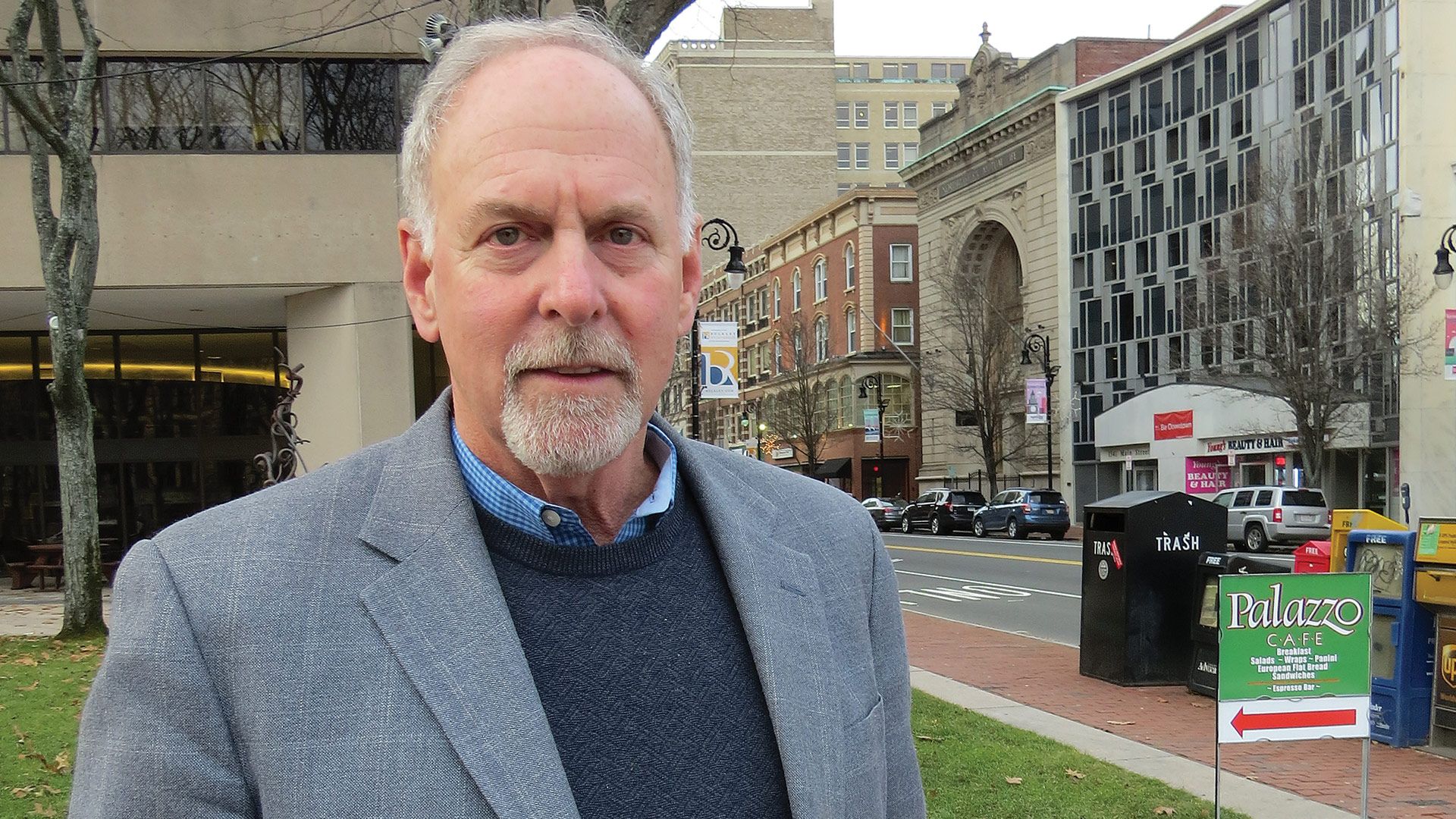

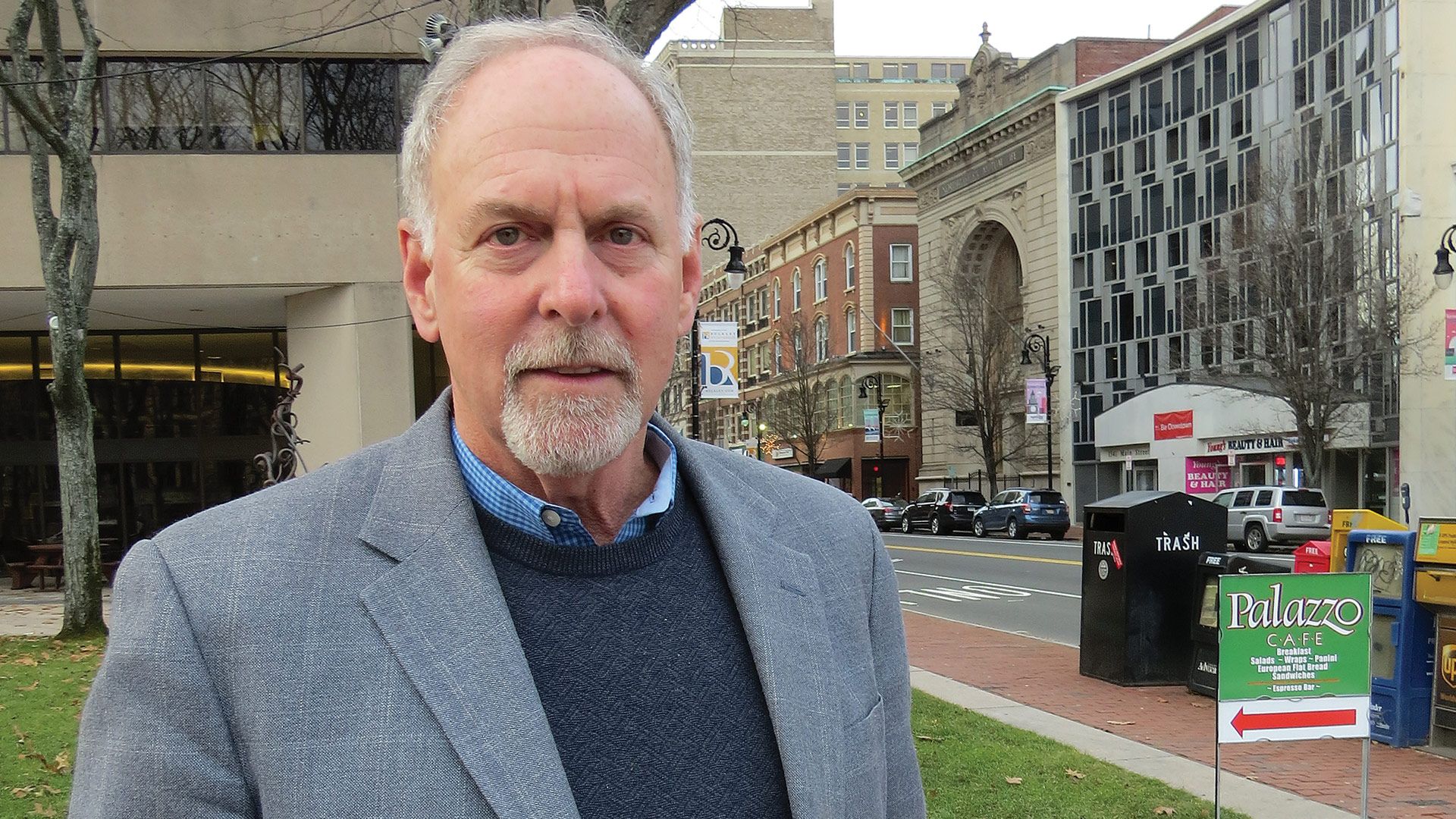

Evan Plotkin says congestion and sky-high rents in Boston demand creative solutions. One of them could be incentivizing companies to move west, into Springfield’s downtown.

Evan Plotkin was talking about how “something has to give.”

With that one phrase, he was talking about the commercial real-estate markets in the central business districts of Boston and Springfield.

In the Hub, said Plotkin, president of NAI Plotkin, rents are sky-high and continue to climb — to more than $100 per square foot in some locations and to roughly $63 per square foot on average, with more space being built to accommodate soaring demand. Meanwhile, traffic, congestion, and problems with mass transit are strangling businesses, he said, to the point where meetings can’t start until 10 a.m. and overall productivity is impacted.

Meanwhile, in Springfield, rents are low — less than one-third the average in Boston — and they are flat, as in consistently flat. “They really haven’t gone up at all in maybe 25 years,” said Plotkin, who noted that there are several reasons for this, but especially the fact that there is, by his estimate, roughly 600,000 square feet of vacant class A space in Springfield’s downtown.

Exacerbating this relative stagnancy in the City of Homes has been new and seemingly unneeded inventory coming on the market — especially the 60,000 square feet at Union Station and the redeveloped property known as 1550 Main — and movement among a growing number of businesses to reduce their physical footprint by enabling (or in some cases requiring) employees to work from home.

This is where the ‘something has to give’ part comes in, said Plotkin, in a very candid interview with BusinessWest, noting that things need to change in both cities. And both would seemingly benefit if just some of the state offices now based in the Hub, as well as many different types of private businesses, would change their mailing address from Boston to Springfield when their leases expire.

“There’s 70% rent inflation in Boston, so when these businesses’ leases expire, they’re looking at incredibly high turnover rent,” said Plotkin, who co-owns a portion of the office tower known as 1350 Main St. He noted that class A rents in Boston have climbed $12 to $15 per square foot over the past few years. Meanwhile, in Springfield, property owners are charging $15 to $20 per square foot of class A space.

“It’s outrageous what’s going on in Boston — and everyone can do the math,” he said. “If state agencies don’t have to be in Boston, they can be decentralized and relocated to office space in Springfield or perhaps Worcester. They’re looking for creative solutions for Boston, and this could be one of them.”

Besides these opinions, all Plotkin really has at this point are those numbers he mentioned earlier (as well as some other statistics) and what appears to be that sound theory — that businesses and state agencies that don’t really need to be in Boston could and should be incentivized to seek other locations, including the 413 and especially downtown Springfield.

He has meetings planned with other downtown property owners as well as Rick Sullivan, present of the Economic Development Council of Western Mass., to discuss what can and perhaps should be done to at least raise awareness of what Springfield has to offer and perhaps create some migration west.

Plotkin said he understands there are reasons why state agencies and businesses want to be in Boston — especially because they know there’s a skilled workforce there — and he understands that moving about 90 miles west on the Turnpike is expensive and presents some risks, especially when it comes to workforce issues.

But he says the numbers speak for themselves, and if those paying sky-high rents in Boston could come to understand the numbers in this market, they could become inspired to relocate.

And if high-speed rail between Boston and Springfield becomes a reality, then people could, in theory, live in the Boston area and work in businesses and agencies relocated to the 413 — a decidedly differently spin on how that service might change the business landscape in the Bay State.

That’s a very large number of ‘ifs,’ and Plotkin acknowledges this as well. But as he said at the top, and repeatedly, something has to give in both cities.

Space Exploration

As he talked with BusinessWest, Plotkin continually leafed through the pages on a white legal pad he brought with him.

They contain various notes he’s collected over the past weeks and months on the Boston real-estate market and the overall business climate in New England’s largest city.

There are some statistics he’s collected — such as those regarding average rents in the Hub, the amount of new space under construction (2.5 million square feet was the number he had), and the current vacancy rate in the city — an historically low 6%, according to the New York-based real-estate giant Cushman & Wakefield.

But there were also some general thoughts, observations, and notations from various publications and other sources.

Among them was a quote from the Massachusetts Biotechnology Council citing a survey which revealed that 60% of the life-science employees working in Boston would “change their job tomorrow” if they could get a better commute. There was also something he read in another publication (he couldn’t remember which one), noting that many Boston-area residents had simply given up on mass transit because it was so unreliable and were instead driving to work and getting there mid-morning.

“In one report I read, business owners in Boston said they had to add staff to make up for transit delays,” he said, putting a verbal exclamation point behind that comment. “Think about how disruptive that is to your business. We don’t understand that here — there’s no such thing as traffic in Springfield.”

Summing up all he’s read and heard about Boston and possible solutions to its congestion problems — everything from incentivizing employers to let workers telecommute to taxing motorists for using certain roads at certain hours — he said the situation is fast becoming untenable for many living and trying to do business there.

“You have inefficiency, spiraling upward costs, shortages of affordable housing, transportation problems, congestion, and sky-high cost of living there,” he said. “Businesses locate in Boston because they can attract that workforce, which makes sense, but if that workforce can’t afford to live there and can’t deal with the congestion, then what’s the point of being in Boston?”

Which brings him back to Springfield and its downtown. And for this subject, Plotkin didn’t need a legal pad.

He’s been working in, and selling and leasing commercial real estate in, downtown Springfield for more than 40 years. He knows what’s changed and, perhaps more importantly, what hasn’t, especially when it comes to demand for space in the central business district, and what would be called net gains.

Indeed, Plotkin said that what the region has mostly experienced — there have been some notable exceptions, to be sure — is companies moving from one downtown office building to another.

In this zero-sum real-estate game, one building owner loses a tenant, and another gains one — but the city and its downtown don’t gain much at all, he said.

“There’s been negative absorption in the downtown for many years now, and I don’t see anything really changing,” he told BusinessWest. “I’m seeing people moving from one block to another, one office building to another, but not many new businesses moving in. Meanwhile, everyone’s vying for the same tenants, which drives the rental rates down even lower than they have been historically; it’s a tenant’s market here.”

It’s anything but that in Boston, which has seen a surge of new businesses moving in — everything from tech startups to giant corporations, like GE. The real-estate market is exploding, and traffic woes and mass-transit headaches have been consistent front-page news. All this calls for creative thinking — as in very creative — and perhaps looking west, said Plotkin, who did some simple math to get his point across.

“Using the example of a 20,000-square-foot tenant paying $63 per square foot in Boston … if the same tenant came to Springfield and paid $18 per square foot, we’re talking about millions of dollars,” he explained, adding that these numbers should strike a chord, especially when it comes to businesses and agencies that don’t have to be in Boston.

Many of those who think they do need to be in Boston are focused on workforce issues, he went on, adding that he believes the Greater Springfield area can, in fact, meet the workforce requirements of many companies.

And over the past several years, the city has become more vibrant with the addition of MGM Springfield, said Plotkin, adding that there are certainly other selling points, like a high quality of life and a cost of living that those residing in and around Boston might find difficult to comprehend.

Bottom Line

As he talked with BusinessWest, Plotkin all but acknowledged that getting businesses and agencies to trade Boston for Springfield will be difficult, for all the reasons stated above.

But the situation in the Hub could be reaching a tipping point when it comes to affordability, traffic, congestion, and quality of life.

And these converging factors might, that’s might, finally convince some decision makers to seek a very creative alternative.

George O’Brien can be reached at [email protected]