When It Comes to Land Preservation, He’s Been a Trailblazer

Leah Martin Photography

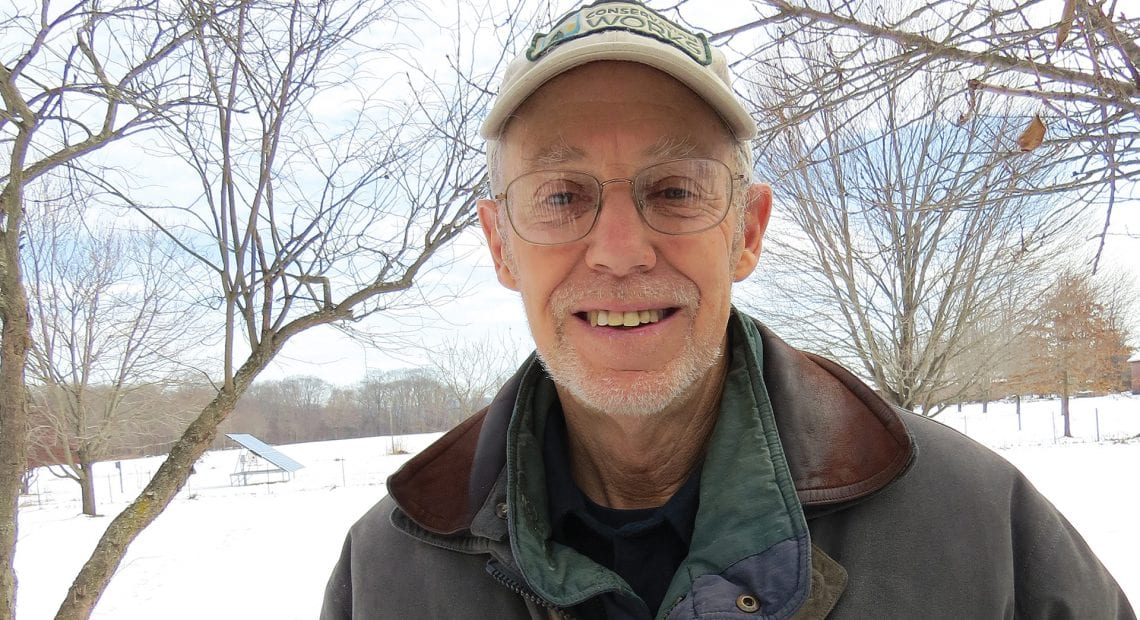

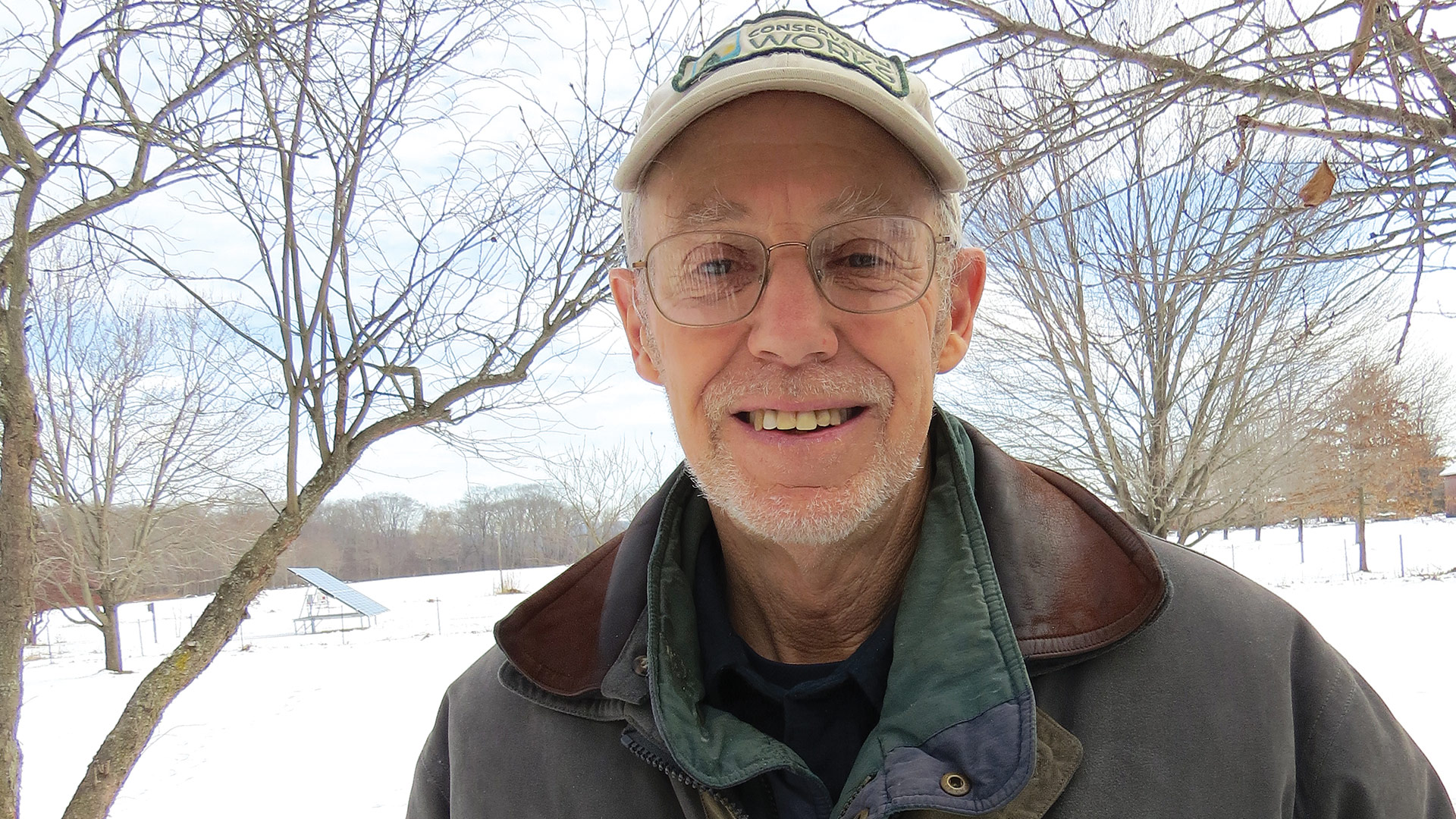

Pete Westover says his appreciation of, and passion for, outdoor spaces traces back to a family vacation trip to, among other places, Rocky Mountain National Park in Colorado, or Rocky, as it’s called, when he was 12.

The park, which spans the Continental Divide, is famous for its grand vistas, high alpine meadows, and dramatic walking trails, some of them at elevations of 10,000 feet or more. And, suffice to say, the park made quite an impression on the young middle-school student.

“There’s bighorn sheep and mountain goats and all kinds of great wildlife and flora,” he noted, adding that he’s been back several times since. “The road goes well over 11,000 feet, so you’re up there among the peaks.”

It was this trip that pretty much convinced Westover he wanted to spend his working life outdoors. And if he needed any more convincing, he got it while working in a hospital just after high school, at a time when he was still thinking about going to medical school and following in the footsteps of his father, who became a doctor.

“I realized, there’s no way I want to spend my time in time in a hospital or a clinic,” he told BusinessWest, adding that he instead pursued a master’s degree in forest ecology at the Yale School of Forestry and Environmental Studies.

“Pete has dedicated his entire career to conserving land and creating trails — the Valley’s forests and farms simply would not be as intact as they are today if Pete Westover hadn’t been a prime champion for their protection.”

Thus, as they might say in what has become his line of work, he took a different trail than the one he originally envisioned. Actually, those who know him would say he’s blazed his own trail — in every aspect of that phrase.

It has led to an intriguing and highly rewarding career that has included everything from work on a helicopter forest-fire crew in Northern California when he was in college to a 30-year stint as conservation director for the town of Amherst, to his current role as founder and partner of Conservation Works, a conservation firm involved with open space and agricultural land protection; ecological and land-stewardship assistance to land trusts, towns, colleges, and other entities; and other services.

Described as a “legend” by one of those who nominated him for the Difference Maker award, Dianne Fuller Doherty, retired executive director of the Massachusetts Small Business Development Center Network’s Western Mass. office (and a Difference Maker herself in 2020), Westover has earned a number of accolades over the years.

These include the Valley Eco Award for Distinguished Service to Our Environment, in his case for ‘lifetime dedication and achievement’; the Governor’s Award for Open Space Protection; the Pioneer Valley Planning Commission’s Regional Service Award; the Massachusetts Assoc. of Conservation Commissions’ Environmental Service Award; and even the Millicent A. Kaufman Distinguished Service Award as Amherst Area Citizen of the Year.

Pete Westover, center, with fellow Conservation Works partners Chris Curtis and Elizabeth Wroblicka in Springfield’s Forest Park, where the company is currently working on several projects.

And now, he can add Difference Maker to that list, a title that certainly befits an individual who has preserved thousands of acres of land, created hundreds of miles of trails, and even helped innumerable parks and other open spaces identify and hopefully eradicate invasive species.

“Pete has dedicated his entire career to conserving land and creating trails — the Valley’s forests and farms simply would not be as intact as they are today if Pete Westover hadn’t been a prime champion for their protection,” wrote Kristin DeBoer, executive director of the Kestrel Land Trust, a partner and client of Conservation Works on many of its projects, in her nomination of Westover. “The number of conservation areas and protected farms that Pete has been involved with are too many to name.”

While justifiably proud of what’s been accomplished in these realms over the past several decades, Westover stressed repeatedly that this work has never been a one-man show. Instead, it’s always been accomplished through partnerships and teamwork, especially when it comes to Conservation Works.

“This is such a great valley to work in,” he told BusinessWest. “There are so many dedicated people in our field; we’re just lucky to be in a place where there are so many forward-looking people.”

Westover is certainly one of them, and his work (that’s a broad term, to be sure) to not only protect and preserve land, but educate others and serve as a role model, has earned him a place among the Difference Makers class of 2021.

Changing the Landscape — Or Not

It’s called the Robert Frost Trail, and it’s actually one of several trails in the Northeast named after the poet, who lived and taught in this region for many years.

This one stretches 47 miles through the eastern Connecticut River Valley, from the Connecticut River in South Hadley to Ruggles Pond in Wendell State Forest. Blazed with orange triangles, the trail winds through both Hampshire and Franklin counties, and includes a number of scenic features, including the Holyoke Range, Mount Orient, Puffer’s Pond, and Mount Toby.

And while there are literally thousands of projects in Westover’s portfolio from five decades of work in this realm, this one would have to be considered his signature work, first undertaken while he was conservation director in Amherst, but a lifelong project in many respects.

Indeed, those at Conservation Works are working with Kestrel on an ongoing project to improve the trail. But the Robert Frost Trail is just one of countless initiatives to which Westover has contributed his time, energy, and considerable talents over the years. You might say he’s changed the landscape in Western Mass., but it would be even more accurate to say his work has been focused on not changing the landscape, and preserving farmland and other spaces as they are.

And even that wouldn’t be entirely accurate. Indeed, Westover said, through his decades of work, he hasn’t been focused on halting or even controlling development, but instead on creating a balance.

“When I worked with the town of Amherst, our philosophy was, ‘we’re not trying to prevent development; we’re trying to keep up with it,’” he explained, adding that this mindset persists to this day. “For every time you see a new subdivision go up, it makes sense to address the other side of the coin and make sure there are protected lands that people can have for various purposes.

“When you see real-estate ads that say ‘near conservation area,’ or ‘next to the Robert Frost Trail’ … that’s important to the well-being of a town or the region to have that balance,” he went on, adding that it has essentially been his life’s work to create it.

Top, Conversation Works partner Dick O’Brien supervises volunteers at Lathrop Community in Northampton in bridge building on the Lathrop Trail off Cooke Avenue. Above, several of the company’s partners: from left, Fred Morrison, Dick O’Brien, Molly Hale, Chris Curtis, and Laurie Sanders.

Tracing his career working outdoors, Westover said he started at an environmental-education center in Kentucky, where he worked for three years. Later, after returning to Yale for a few more classes, he came to Amherst as its conservation director, a role he kept from 1974 to 2004. In 2005, he would partner with Peter Blunt, former executive director of the Connecticut River Watershed Council (now the Connecticut River Conservancy) to create Conservation Works. Blunt passed away in 2010, but a team of professionals carries on his work and his legacy, and has broadened the company’s mission and taken its work to the four corners of New England and well beyond.

But over the years, Westover has worn many other hats as well. He’s been an adjunct professor of Natural Science, principally at Hampshire College, where he has taught, among other courses, “Conservation Land Protection and Management,” “The Ecology and Politics of New England Natural Areas,” “Ecology and Culture of Costa Rica,” “Geography, Ecology, and Indigenous Americans in the Pacific Northwest, 1800 to Present,” and, most recently, “Land Conservation, Indigenous Land Rights, and Traditional Ecological Knowledge.”

He’s also penned books, including Managing Conservation Land: The Stewardship of Conservation Areas, Wildlife Sanctuaries, and Other Open Spaces in Massachusetts, and served on boards ranging from the Conservation Law Foundation of New England to the Whately Open Space Committee.

“When I worked with the town of Amherst, our philosophy was, ‘we’re not trying to prevent development; we’re trying to keep up with it. For every time you see a new subdivision go up, it makes sense to address the other side of the coin and make sure there are protected lands that people can have for various purposes.”

But while he spends some time behind the keyboard, in the lecture hall, or in the boardroom, mostly he’s where he always wants to be — outdoors — especially as he works with his partners at Conservation Works on projects across New England and beyond.

The group, which now includes seven partners, handles everything from conservation of open space and farmland to the development and maintenance of trails; from invasive-plant-management plans to what are known as municipal vulnerability-preparedness plans that address climate change and the dangers it presents to communities.

And, as Westover noted, teamwork is the watchword for this company.

“One of the things that attracted me to Conservation Works is that all of the professionals have very unique skills, and we all complement one another,” said Elizabeth Wroblicka, a lawyer and former director of Wildlife Lands for the Massachusetts Division of Fisheries and Wildlife. “Land conservation is multi-faceted, from the acquisition to the long-term ownership to the stewardship, and with the wildlife biologists we have, the trail constructors, boundary markings … I do the contracts, but we all have a piece that we excel in.”

Chris Curtis, who came to Conservation Works after a lengthy career with the Pioneer Valley Planning Commission as chief planner and now focuses extensively on climate-change issues, agreed. He noted that, in addition to land preservation, trail-building and improvement, and other initiatives, the group is doing more work in the emerging realm of climate resiliency — out of necessity.

“We’ve been working with the town of Deerfield for four years,” he said, citing just one example of this work. “We’ve helped it win grants for more than $1.2 million worth of work that includes a municipal vulnerability-preparedness plan, flood-evacuation plans, a land-conservation plan for the Deerfield River floodplain area, and education programs, including a townwide climate forum that was attended by 200 to 300 people.”

Such efforts to address climate change are an example of how the group’s mission continues to expand and evolve, and how Westover’s broad impact on this region, its open spaces, and its endangered spaces grows ever deeper.

Seeing the Forest for the Trees

Reflecting back on that trip to Rocky, Westover said that, in many ways, it changed not only his perspective, but his life.

It helped convince him that he not only wanted to work outdoors, but wanted to protect the outdoors and create spaces that could be enjoyed by this generation and those to come. As noted, he’s both changed the landscape and helped ensure that it won’t be changed.

He’s not comfortable with being called a legend, but Difference Maker works, and it certainly fits someone whose footprints can be seen all across the region — literally and figuratively.

George O’Brien can be reached at [email protected]