Building Blocks for the Future

Dr. Lynnette Watkins called 2023 a rebuilding year and a time for “getting back to basics.”

As she talked about the relative fiscal health of hospitals, and especially Cooley Dickinson Hospital (CDH) in Northampton, which she serves as president and CEO, and the outlook for the coming year, Dr. Lynnette Watkins looked back on 2023 and described it with phrases often reserved for struggling sports teams — yes, like the one in Foxboro.

“It’s been a very challenging year,” she told BusinessWest. “It was definitely a rebuilding year, with a lot of focus on getting back to basics, and getting to what I would call a new normal.”

While we’re used to hearing those terms in sports, they work in healthcare, and especially when it comes to hospitals, said Watkins and others we spoke with.

Indeed, hospitals are rebuilding from several years of turmoil, falling revenues, rising costs, and struggles with recruiting and retaining a workforce. Many of these issues predate the pandemic, to one extent or another, but COVID certainly exacerbated the problems.

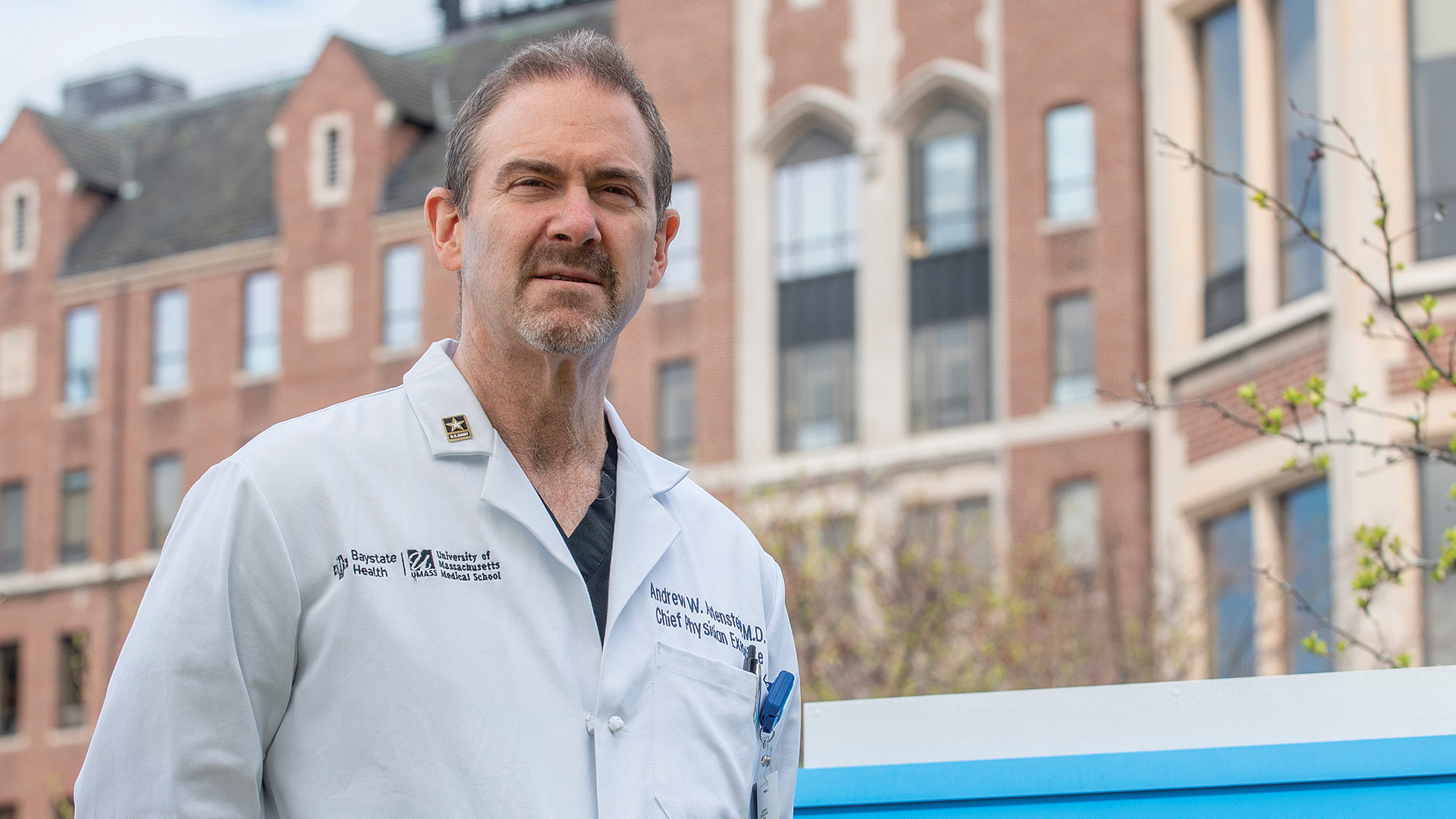

Dr. Mark Keroack, president and CEO of the Baystate Health system, which includes four hospitals — Baystate Medical Center in Springfield, Baystate Noble Hospital in Westfield, Baystate Franklin Medical Center in Greenfield, and Baystate Wing Hospital in Palmer — put things in perspective with some eye-opening numbers.

“It’s been a very challenging year. It was definitely a rebuilding year, with a lot of focus on getting back to basics, and getting to what I would call a new normal.”

He said the Baystate system, which also includes the health insurer Health New England, a range of physician practices, and a home-health agency (a $3 billion organization), essentially lost $61 million in the fiscal year that ended on Sept. 30 — $44 million from health delivery and $17 million from the health plan, which “had a bad year.”

And that’s a significant improvement over the previous fiscal year, when it lost $177 million.

And when it comes to workforce, the Baystate system has roughly 1,400 openings across several different departments, he said, noting that, again, this is an improvement from the peak of more than 2,000 in 2022.

Spiros Hatiras says HMC has taken aggressive steps on the workforce front, such as large sign-on bonuses and staffing ratios for nurses.

“It’s still more than double what it used to be before the pandemic,” said Keroack, who will be retiring next summer, adding that the system has nonetheless seen progress when it comes vacancy rates, turnover rates, and overall retention through strategies including flex scheduling, workforce-safety initiatives, upward movement on salaries and benefits, wellness programs, career counseling, and more — progress he expects will continue on these and other fronts in 2024.

Dr. Robert Roose, president of Mercy Medical Center in Springfield, agreed there was some improvement in 2023 on several of the fronts on which hospitals are battling, from overall volumes in the ER and with hospital stays (sometimes for the wrong reasons) to decreased use of travel nurses and their sky-high costs.

But there are still formidable challenges in the form of higher costs for everything from labor to equipment to medication; inadequate reimbursements for care (a problem hospitals have been dealing with for decades now); and, most recently, backlogs on the patient floors and the ER resulting from a shortage of nursing-home beds.

Overall, there are still many “mismatches,” as he called them, when it comes to demand in various settings and with specific needs, such as behavioral health.

“Hospitals are at a crossroads,” Roose said, noting that the pressures currently facing them will not likely abate in the years to come. “We have to think about how we focus on three main areas — health equity, system redesign and how we can do things differently, and workforce development.”

When it comes to getting back to basics, that phrase applies to everything to improving access, through initiatives such as an expansion of the ER at CDH (more on that later), to different strategies for recruiting and retaining employees — everything from greater flexibility with hours to a concert to celebrate nurses.

In that latter realm, there is certainly room for innovation and even what amounts to risk taking, said Spiros Hatiras, president and CEO of Holyoke Medical Center and Valley Health Systems, who said he and his team have certainly done so with some aggressive initiatives with bonuses for nurses, staffing ratios, and taking on nursing students right out of college.

“Hospitals are at a crossroads. We have to think about how we focus on three main areas — health equity, system redesign and how we can do things differently, and workforce development.”

Elaborating, he said HMC took some of the federal and state money funneled to hospitals in the wake of the pandemic and “invested” in programs to bolster the workforce through initiatives such as rising pay scales and benefits, ratios, and especially bonuses for nurses, both recent graduates and those with years of experience — initiatives that have generated strong results and eliminated the need for travel nurses, as we’ll see later.

For this issue, BusinessWest talked with these hospital administrators about the various forms of progress made in 2023 — and there were several — as well as the stern challenges that remain and the expectations for the year ahead.

Working in Concert

They called it Nurses Rock.

That was the name attached to a concert last spring featuring the local cover band Trailer Trash, staged in the former Colony Club space in Tower Square and orchestrated by Holyoke Medical Center. And that name speaks volumes about what this different kind of event was all about.

Indeed, this was a celebration of nurses, said Hatiras, noting that nurses from across the region, not just HMC, were invited. And more than 400 turned out.

Nurses Rock II is well into the planning stage, he went on, adding that the band Aquanett has been secured, and the event has been scheduled to coincide with National Nurses Week in early May.

Dr. Mark Keroack says 2023 was another difficult year for hospitals, on several fronts, but it was a vast improvement over 2022.

Nurses Rock is just one example of rebuilding, going back to basics, being innovative, and, yes, thinking outside the box when it comes to the many challenges that are still confronting hospitals, which are, in many ways, still digging out from the fiscal turmoil created by, or exacerbated by, the pandemic.

With that, Keroack returned to those numbers he referenced earlier, such as the posted losses of $61 million system-wide in FY 2023, and put them into historical perspective.

“To really understand this, you need to turn the clock back to before the pandemic,” he said. “Before the pandemic, we would routinely generate margins of 2% to 3%, and we were generally stable; we were rated A+ by Standard & Poor’s, which put us roughly in the top quartile of health systems in New England.

“In 2020 and 2021, we were propped up by some generous federal subsidies from the CARES Act,” he went on, adding that these amounted to roughly $180 million. “They papered over some serious financial problems and enabled us to post 1% to 2% margins those two years.”

But that relief went away in 2022, and the system was still left with a huge bill for contract labor and overtime pay, he continued, adding that, when it comes to that $177 million loss in FY 2022, more than 70% of that came from higher labor costs.

In 2023, Baystate was able to make about $170 million worth of margin improvement, Keroack said, adding that much of this resulted from one-time grants from FEMA and ARPA monies, as well as some revenue-enhancement initiatives, efforts to improve supply-chain expenses, and a reduction of roughly 60 positions from the executive leadership ranks.

“We’re running an extraordinarily lean organization right now,” he told BusinessWest. For example, I used to have six direct reports, and now I have 12.”

What’s more, the system “turned the tide,” as he put it, when it comes to the use of contract labor, while also embarking on a number of joint ventures, such as the new behavioral-health hospital that opened recently in Holyoke, that help avoid capital expenditures, and exiting some small lines of business such as in-vitro fertilization and urgent care, areas where Baystate either couldn’t recruit talent or determined that these areas were not the core mission and were better left to others to handle.

Overall, volumes returned in 2023 across the board, Keroack said, meaning in the ER, surgeries, and discharges. But hospital stays or ‘days’ were considerably over budget because length of stay has increased, often because it’s more difficult to discharge a patient to a nursing home or home care.

“Hospitals are at a crossroads. We have to think about how we focus on three main areas — health equity, system redesign and how we can do things differently, and workforce development.”

“It’s causing a traffic jam,” he explained. “And it results in dozens and dozens of patients being stuck, waiting for a discharge to happen; that jams up the in-patient unit, causes backup in the emergency room, long waits, etc. It’s been stressful, but we’re beginning to get some progress on that.”

Watkins agreed, noting that more progress is needed in 2024 and beyond because there are many consequences as hospital stays lengthen, everything from greater potential for hospital-acquired infections and patient falls to further financial hardship for hospitals because insurers will not reimburse for those longer stays.

Much of the problem results from workforce issues, she went on, noting that “workforce drives access — access to our acute-care facilities, access to our ambulatory clinics, access to our VNA and hospice — and it really drives the value and quality of service that we offer.”

Work in Progress

Overall, there has been even more progress on the workforce front, although considerable challenges remain, said all those we spoke with.

Due to a heightened focus on various strategies regarding recruitment and retention, hospitals have greatly reduced their dependence on travel, or contract, nurses, who are paid at rates at least double what staff nurses receive, Watkins said.

At HMC, use of travel nurses has been eliminated altogether, said Hatiras, with a discernable dose of pride in his voice, noting that this was achieved through some rather aggressive risk-taking.

And, overall, the hospital has made itself a good place to work, he said, making it easier to recruit not only nurses but also doctors and other providers as well.

“The main theme in 2023 for us was to really leverage many, many years of work to create a great culture here,” he said. “That work, that culture, enabled us to attract physicians here where otherwise, we would have no shot. And it has essentially enabled us to solve our staffing problem. We have solved it for now — knock on wood.”

The most significant progress has come with attracting and retaining nurses and thus eliminating dependence on travel nurses, he went on, adding this has been accomplished through creation of that culture, but also through large bonuses and staffing ratios, initiatives launched in the early stages of the pandemic that are paying real dividends now.

“We gave the nurses something that no one else wanted to give them — something they really wanted, and something we fought for years not to give them: ratios,” he said. “None of my colleagues like my answer, but it has worked for us.”

Elaborating, Hatiras said that, pre-pandemic, his hospital, and all hospitals, fought hard against ratios demanded by nurses unions, primarily because there was no flexibility built into the equation, and penalties were imposed upon those who did not comply. HMC has injected some flexibility, keeping a 5-to-1 ratio whenever possible.

Meanwhile, rather than spend pandemic-related state and federal assistance on the “middleman,” meaning agency nurses for which the hospital paid $200 per hour, the hospital opted to put it toward retention bonuses and other initiatives for nurses and other providers of care.

“We basically said, ‘you’re here, and you work for us; we don’t want you to leave — so we’re going to pay you $20,000 over the next four years as a bonus, just to stay,’” he said, adding that very few nurses who accepted those terms have left.

Meanwhile, more recently, the hospital decided to make some additional investments, this time in recent college graduates, at a time when fewer hospitals were taking on such inexperienced individuals because of the high cost of training them. HMC offered them the chance to join the staff in May, after graduating, but not take on a full patient load until October.

On top of that, it offered something most “couldn’t say no to” — a $50,000 sign-on bonus for a commitment to stay five years.

“We said, ‘listen, we’ll cut you a check so long as you sign a note that says you’ll come and work for us,’” he said, adding that these bonuses were larger than most being offered and upfront in nature.

And they have worked, with many recent graduates signing on. And while many of his colleagues have questioned his math, Hatiras has told them, as he told BusinessWest, that, in the long run, it’s more cost-effective to incentivize nurses to stay in this aggressive fashion than it is to replace them when they leave. And that same guiding philosophy prompted him to put in place a similar program for experienced nurses, one that offers them $40,000 bonuses if they stay three years.

Reality Check

While there has been progress on workforce issues and other fronts, there are still a large number of pain points for hospitals, said Roose, adding that these will certainly continue in 2024.

“The pressures on hospitals have been increasing; they’ve been changing, and the needs of our community have been changing over the past several years, but the pressures have not relented,” he said, noting that the pandemic exacerbated the workforce crisis and compounded a financial crisis for hospitals across the country.

“Those various elements lead to pressures on everything from access to care for patients through traditional models that we’ve had for the past several decades, to having enough colleagues to provide care to meet the demands in different kinds of settings, to how to continue to invest in resources to innovate and grow to where healthcare is going.”

Moving forward, he said the healthcare system must continue to evolve to meet the changing needs of the public and continue to provide access to care, especially amid an ongoing shift toward more care being provided in outpatient settings.

“Hospitals and healthcare systems are evolving, but perhaps not quick enough to best meet those needs,” he went on. “We need to provide access points of care that are the most convenient, that are readily available, at the right level of care when needed, and with a high level of excellence.”

Watkins agreed, but noted that, while 2023 was certainly a time of ongoing challenge and duress for hospitals, it was also a period for rebuilding and, at CDH, celebrating such things as the 10th anniversary of the hospital’s partnership with Mass General Brigham, an expansion and renovation of the hospital’s labor and delivery suites, and the advancement of plans for expanding the ER, a project that will greatly enhance the delivery of care in that unit.

Ground will be broken on the new facility shortly, she said, adding that work to enlarge and redesign the ER brings into focus many of the pressing issues in healthcare today — everything from access to care to workplace conditions to retention of talent.

All are addressed in a design that adds 7,000 square feet of space but also improves safety through an overall configuration that enhances lines of sight while also improving staff satisfaction.

“They want to be in an environment that is pleasing to them, that they can move around in, because we spend a lot of the day at work,” Watkins said. “All of these things come back to workforce, which is going to be the key driver as we move into 2024.”

Bottom Line

As he talked briefly about his pending retirement and tenure at Baystate, Keroack joked that it has “never been dull.”

That’s an understatement and a rather polite way of summing up the past few years in particular.

It’s been a time of extreme challenge, but also intriguing and sometimes even exhilarating work to confront those challenges and find solutions.

As for what is to come and the outlook for 2024, hospitals will continue to rebuild and stress the basics. And, like any struggling sports team, they’ll look forward to the new year with optimism.

That’s the best you can do when you’re at a crossroads.

I will argue that all is not well with our healthcare system, and that the average U.S. hospital is facing tremendous challenges now and for the foreseeable future.

I will argue that all is not well with our healthcare system, and that the average U.S. hospital is facing tremendous challenges now and for the foreseeable future.