Nurse, Urology Group of Western New England

During Her Long Career, She Has Made a World of Difference

Now 87, almost 88, Joanne (Jody) O’Brien is two decades and change past what the Social Security Administration considers ‘full retirement age.’

But she is still working — two days a week as a triage nurse for the Urology Group of Western New England (UGWNE), in its Northampton office. She’s doing plenty of other things to keep busy, which we’ll get to, but for now, let’s focus on her day job — and the fact that she still has one.

When asked why, her face curves into a huge smile — it seems to be almost permanently like that — and she offers a simple and direct explanation.

“I love nursing,” she told BusinessWest with a voice that would imply this would be obvious if she’s been doing it for more than 67 years. But she wanted to elaborate, and did.

“I lucked out picking nursing as a profession coming out of high school because it’s just been the most rewarding career I could possibly imagine,” she said. “I’ve enjoyed it so much that I don’t want it to end. As long as someone keeps me employed, I’ll keep coming to work.

“I absolutely love what I do — I can’t say enough about how great nursing has been for me,” she went on. “It’s a wonderful career to have. I’ve tried so many different aspects of it, and I’ve loved them all. So I figured there’s no sense packing it in if you love what you’re doing.”

Her career has placed her in many settings — from a hospital ship that was part of Project Hope in the early ’60s to Western New England College, where she was director of Health Services; from an eye-surgery office in Hawaii to the Hampden County Jail and House of Correction, where she was a per-diem nurse and, later, director of nurses, with many other stops as well.

“I lucked out picking nursing as a profession coming out of high school because it’s just been the most rewarding career I could possibly imagine. I’ve enjoyed it so much that I don’t want it to end. As long as someone keeps me employed, I’ll keep coming to work.”

But longevity and this variety of professional settings only begins to explain why O’Brien has been chosen as a Healthcare Hero for 2023 in the Lifetime Achievement category. Beyond her various day (and night) jobs, she has undertaken a number of service and volunteer assignments — from reading at Valley Eye Radio to taking care of orphans in Romania; from teaching English to nursing students in China to tagging sharks in Belize; from restoring and protecting turtle habitats in Costa Rica to working at Whispering Horse Therapeutic Riding, supporting riders with disabilities.

All this suggests she could easily have been nominated in several, if not all, the categories of Healthcare Heroes. Because of the length, variety, and broad impact of her work, she is being honored in the Lifetime Achievement category, one that has traditionally been dominated by administrators. In this case, though, it is going to a provider. A provider of care. A provider of hope. A provider of inspiration.

Jody O’Brien with staff members at the Urology Group of Western New England’s Springfield office.

Staff Photo

Through her 87 years, 67 of them as a nurse, she has seen just about everything, including a global pandemic. Summing it all up, she said her passion for helping others hasn’t dimmed — and has probably only grown stronger — nearly 70 years after she entered nursing school.

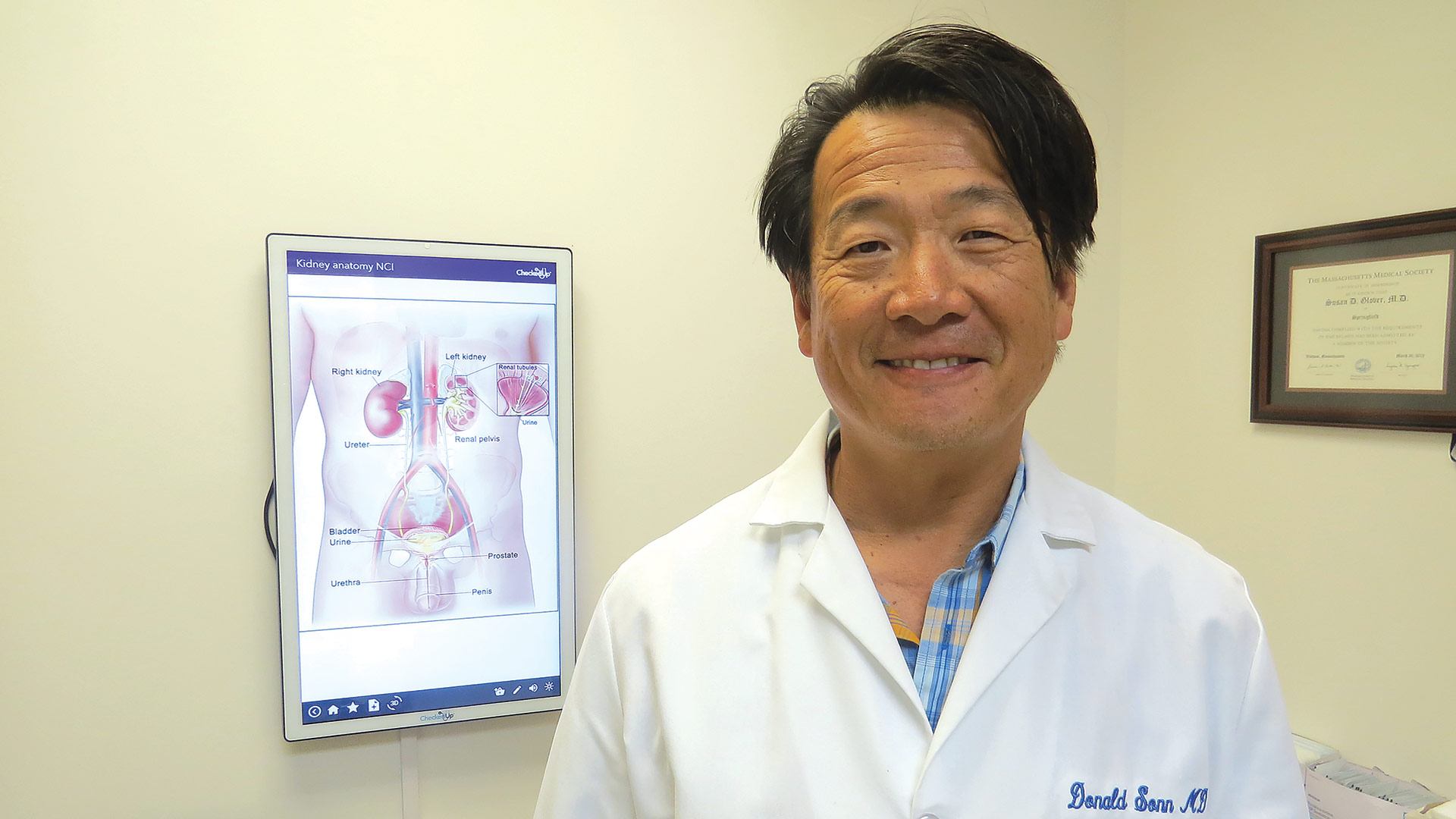

This enthusiasm and energy was conveyed by Dr. Donald Sonn, a physician with UGWNE, who was among those who hired her 18 years ago.

“When we first interviewed her, we were struck by how positive and effervescent she was, and how energetic she was,” he recalled. “I’m constantly amazed by her energy and her positive attitude.”

Calling her an “ombudsman” for the practice’s patients, Sonn said O’Brien consistently draws praise for her calm, steady hand (and voice on the phone) and her desire to assist others.

All of this — and much more — explains why she is a true Healthcare Hero.

Riding the Wave

‘Cuba si, Yanquis no.’ That translates to ‘Cuba yes, Yankees no,’ and it’s a phrase, and a song, that O’Brien heard repeatedly as she served aboard the USS Hope, the former Navy hospital ship that was chartered to the People to People Health Foundation in 1960, when it was docked in Trujillo, Peru two years later.

“The people who met us at the dock were Communists, and they did not want us there,” she recalled, adding that the exploits of the USS Hope in Peru later became the subject of the book Yanqui Come Back!

O’Brien spent a year on the Hope, earning a $25 monthly stipend. But as those credit card commercials used to say, it was a learning experience that was priceless.

She worked beside a constantly changing team of doctors that performed surgery on the ship and in hospitals on the mainland, with procedures ranging from plastic surgery for burns to work to address cleft palate and hairlip, to removal of tumors, some of which had grown to enormous sizes because the patients hadn’t seen a healthcare provider in years, if not decades.

Urologist Dr. Donald Sonn calls Healthcare Hero Jody O’Brien an “ombudsman” for the practice’s patients.

Staff Photo

“People would walk for miles to get to the ship to be treated, and we treated everyone who needed it,” she recalled. “It was such a learning experience for me working with all these doctors.

“I was still young and adventurous,” she went on as she talked about how she paused her career, sort of, to serve on the ship, adding that she has remained young at heart and has always, in her recollection, been adventurous.

Indeed, the book on her life and career has many intriguing chapters, some of which are still being written. In literary circles, they would call this a ‘page turner.’

Our story starts in Iowa, where O’Brien was born and raised, and where she decided she wanted to be a nurse. She attended nursing school in Davenport — a three-year diploma program that cost $500.

Upon graduation, she took a job in Davenport, but soon thereafter, she went to Hawaii to stay with a friend who had recently had a baby and wanted her company while her husband was deployed.

It was in Hawaii that O’Brien became acquainted with Project Hope. She visited the ship when it was docked and became intrigued with its mission. After returning to Iowa, she filled out an application to serve in Project Hope as an operating room nurse, and in 1962, she was approved for service.

During her year on the USS Hope, she met a volunteer named Ed O’Brien, from Holyoke. Upon returning to Iowa, she would drive to the Paper City to renew acquaintances. They would marry in 1963 and eventually settle in East Longmeadow.

Thus would commence a series of assignments in the 413, but also well beyond it.

Care Package

These included a lengthy stint at what was then Wesson Women’s Hospital, working in labor and delivery, and another as a nurse practitioner in an ob/gyn office.

From 1983 to 1988, she served as director of Health Services at Western New England College, handling the needs of 6,000 students, and also as a per diem nurse at the Hampden County Jail and House of Correction.

She then accepted a travel nurse assignment at Castle Hospital in Kailua, Hawaii. She stayed in Hawaii for a dozen years, also serving as nurse manager of an eye-surgery center and as branch director of Nursefinders of Hawaii. And while in the Aloha State, she earned a master’s degree from Central Michigan University.

“She would go on a trip every three or four months, and it was always something really fascinating — volunteering in some third-world country or teaching children or reading to the blind. She has a tremendous record of service.”

She returned to Western Mass. in 2000 and took a job as area director of Nursefinders of Eastern Massachusetts, and soon thereafter became a flex team manager at Baystate Medical Center, managing 60 RNs, 25 technical assistants, 45 constant companions, and the ‘lift team.’

At the Urology Group of New England, which she joined 18 years ago, she works two days a week — Monday and Wednesday. The former is generally the busiest and perhaps the most difficult of the days of the week, but that’s when the group needs the help, so that’s when she works.

O’Brien’s whole career has been like that, in many respects — showing up when and where the help is most needed.

That’s true professionally, but also in her work as a volunteer, with work that is wide-ranging, to say the least.

Indeed, during the three days she’s not working at the Urology Group — and all through her life, for that matter — she has found no shortage of ways to give back and be there, for both people and animals.

Among them is her work with Valley Eye Radio, where she reads the local newspaper for the benefit of those who can’t read it themselves.

“It makes you feel good to know that, for people who cannot read or have difficulty reading, we can share what’s going on today in Springfield or the United States or the world,” she said. “We can share that information with them.”

Meanwhile, she also volunteers with Greater Springfield Senior Services, helping individuals who can no longer handle their own finances with bill paying and other responsibilities, and with Whispering Horse Therapeutic Riding, a nonprofit that, among other things, brings horses to nursing homes, where residents can feed and pet the animals.

“The way they light up when they see these horses … it’s so gratifying,” she told BusinessWest, adding that she and a colleague will visit facilities regularly — sometimes weekly, other times monthly.

Animals have always been a big part of her life — and her strong track record of giving back. In addition to tagging sharks and restoring turtle habitats, she has also volunteered at animal sanctuaries in Australia to care for koalas, often taking her grandchildren with her on such service trips, introducing them to the many rewards that come with such work.

“At this age, you know you don’t have many more days to fill, so you fill each one of them,” she said, but concedes that she’s always wanted to stay busy.

“She’s done so much in her life … I’ve always looked forward to listening to her talk about trips, her escapades,” said Sonn, choosing that word carefully. “She would go on a trip every three or four months, and it was always something really fascinating — volunteering in some third-world country or teaching children or reading to the blind. She has a tremendous record of service.”

In both aspects of her life — as a nurse and as a volunteer — the common thread has been a desire to help those in need, and this explains why she has been chosen as a Healthcare Hero for 2023.

“I loved working at Western New England; the college kids were a joy to work with,” she said, adding that each stop in her career has been different — and enjoyable. “There’s something about taking care of people and helping them deal with mental and physical problems and seeing what you can do to help them in their lives.”

Still Making a Difference

There are many people who have worked well into their 80s in healthcare. And there are many people who have put dozens of lines on a résumé detailing a lengthy list of career stops.

But there are few who have the passion, dedication, and resolve to use their talents and their love for helping others to make a world of difference, in every aspect of that phrase.

Jody O’Brien is such an individual. That commitment has helped her stand out in this field for seven decades. It makes her a Healthcare Hero. n