Taking Things to a Higher Gear

Bob Charland

While providing BusinessWest a tour of the facilities that were once home to the makers of Absorbine Jr., Bob Charland stopped at the top of the stairs leading to the huge basement.

“You want to see what 2,000 bikes looks like … there you go,” he said, gesturing with his hand toward a room absolutely crammed with bicycles of every color, size, and shape imaginable. “And that’s just a fraction of what we have here.”

Indeed, on the other side of a wall that divides the basement are probably another 1,000 bikes, he said, adding that more are stored in a facility in Palmer and still more in a trailer. Meanwhile, in other parts of the massive home for the nonprofit known as Pedal Thru Youth, several hundred bikes are in various stages of being ready for delivery to various constituencies, including 200 that are ready for delivery to working homeless individuals in Hartford.

These rooms filled with bikes go a long way toward telling the story of this unique individual known to most as simply “the Bike Man” and the nonprofit he created four years ago. But there is much more to that story as well, as his tour makes clear.

“There’s nothing in the stores; I was in a bike shop the other day, and there were maybe four bikes there, and these were the high-end models that sell for a few thousand dollars.”

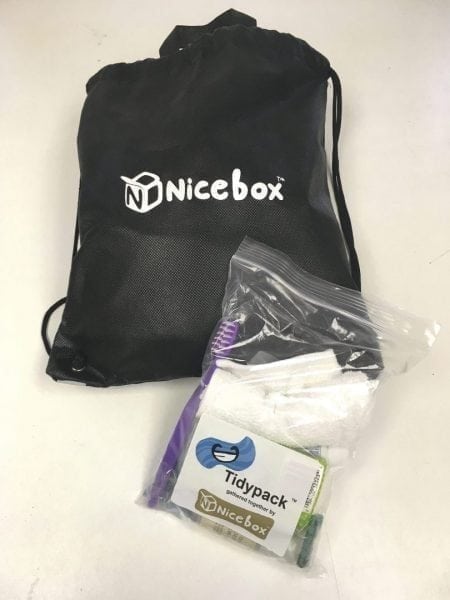

There are also large supplies of clothes for the needy here, as well as backpacks filled with health supplies bound for the homeless, wheelchairs being retrofitted, and bicycles customized for those with special needs.

There’s also a bedroom that Charland adjourns to when he’s working very late (which happens often) and is simply too tired to drive home — which happens “once in a while.”

Collectively, the stops on the tour tell of the mission and the inestimable energy and passion that Charland brings to his work, which has certainly evolved since he launched Pedal Thru Youth and evolved even further in the wake of the pandemic.

Changing Lanes

Indeed, when COVID-19 shut down schools (to which this agency provides a large number of bikes), the economy in general, and non-essential businesses and nonprofits, Charland shifted to making cloth masks and distributing them to police departments and other destinations.

“I was bored,” he said when recalling those first few weeks after COVID arrived. “I know how to sew, so I started sewing face masks at home with my stepson. We then started putting the masks, hand sanitizer, and gloves in backpacks and handing them out to police departments, because those departments certainly weren’t ready for COVID — they didn’t have enough supplies.”

Just some of the thousands of bikes waiting to be repaired and prepared for delivery to children, veterans, and other constituencies at the headquarters for Pedal Thru Youth in Springfield.

The story went viral on social media, and People magazine published a piece that caught the attention of Samsonite, which sent Charland some industrial sewing machines, fabric, and elastic so he could ramp up production of masks.

“We ended up having nine sewing machines out in the community,” he said, adding that he soon had more than 100 masks coming his way each day that he started distributing to senior centers, nursing homes, and a host of police departments.

Because of that initiative, Charland’s agency was deemed essential. And soon, most of the focus was back on bikes and other, more traditional aspects of its mission. But there was some pivoting as well.

With schools closed, many of the donations of bicycles shifted to the homeless and veterans groups, he noted, adding that he also teamed up with the Massachusetts Military Support Foundation to bring food to veterans’ organizations.

Getting back to bicycles … this is still the primary mission of Pedal Thru Youth, and the work of repairing and readying those thousands of bikes that have been donated or collected by police departments, public-works employees, and others has gone on throughout the pandemic.

The donations have mostly been much smaller in scale — again, because most schools remain closed or not open to the public — but Charland has improvised.

“There’s nothing in the stores; I was in a bike shop the other day, and there were maybe four bikes there, and these were the high-end models that sell for a few thousand dollars.”

“We did a very large donation of bikes, 169 of them, to West Springfield, but, because the schools were closed, we had to go house to house to deliver the bikes to individual families,” he said, adding that now, as the pandemic is easing, there is greater demand and an even a greater sense of urgency — if that’s possible.

That’s because bicycles — and bicycle parts — are now firmly on the growing list of items that are in demand, but also short supply. As in very short. During COVID, with children out of school, demand for bikes soared, Charland explained, adding that manufacturers have struggled mightily to build inventory amid supply-chain issues.

“There’s nothing in the stores; I was in a bike shop the other day, and there were maybe four bikes there, and these were the high-end models that sell for a few thousand dollars,” he said, adding that this dynamic is generating more individual requests for bikes from families and nonprofits in need.

Pedal Thru Youth is better equipped to handle larger requests and bulk deliveries of a few dozen or a few hundred bicycles, but, out of necessity, it has adjusted, as with those deliveries to West Springfield families. Overall, he meets roughly 90% of the individual requests for bicycles.

He tries to meet this demand not all by myself, but pretty close.

He has some help from some volunteers, including a few individuals involved in the program called Roca, which strives to end recidivism and return offenders to society through job placement and other initiatives. They assist with basic repairs to bicycles — Charland handles the more difficult work — and getting them ready for transport.

On average, he and his volunteers will get roughly 20 bikes ready for the road each day, said Charland, adding that many of the donated bikes are in decent shape, and those needing considerable work are often stripped down for parts.

In addition to traditional bicycles, requests are soaring for bikes for children with special needs. And they come from not only Western Mass., but across the country. Charland had a few ready to go out the door on the day BusinessWest visited, but there are roughly 90 requests for such bikes on his desk.

Pedaling On

Meanwhile, as he goes about meeting these requests, he battles a number of health issues, most recently three hernias, and shoulder and kidney issues that now keep him from working for a living and waging legal battles for workers’ comp. This is addition to a head injury that has long impacted his quality of life.

He said he soldiers on because of the satisfaction he gets from his various efforts, especially the delivery of a bicycle — and a helmet, water bottle, and first-aid kit — to a child in need.

“I love what I do,” he said simply. “This is a lot of fun, and to see the look on the kids’ faces … that’s what drives me.”

George O’Brien can be reached at [email protected]