A Promise for the Future

Springfield’s School Superintendent Sets the Bar High

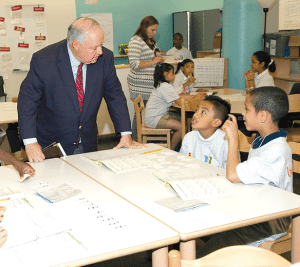

Superintendent Daniel Warwick pays frequent visits to the district’s 54 schools and enjoys interacting with students.

Warwick has been on the job since last July, and his goals are lofty, given the fact that 85% to 90% of the city’s students come from low-income families, which creates a host of academic, social, and emotional challenges. But his deep commitment and history of success prove that he knows what it will take to fulfill what he calls “The Springfield Promise: A Culture of Equity and Proficiency to Raise the Bar and Close the Gap.”

arwick wants to lower the dropout rate and increase the graduation rate, which stood at 11.7% and 52.1%, respectively, last year. His vision is to create a district where “parents and community members move into Springfield for the privilege of sending their students to schools that are striving in a culture of equity and proficiency.”

It’s no easy task, as the system serves approximately 26,000 students in 46 schools at 54 sites, including eight alternative programs. They speak numerous foreign languages and are from diverse family, religious, and ethnic backgrounds. “In schools with high levels of poverty, there are good excuses to rationalize poor performance. But I approached the job with a no-excuses mantra and the attitude that we are going to change the outcome for our students,” Warwick said,

His reasoning is based on past endeavors in Springfield, honed during his tenure as principal at Glenwood School in the Liberty Heights section of the city. “When I took it over, it was one of the lowest-performing schools in the Commonwealth,” Warwick said.

But he instituted measures that turned it around, and within a few years, “Glenwood was the highest-performing high-poverty school in the state,” the superintendent noted, adding that he was feted with a bevy of state and national awards, including the coveted National Blue Ribbon School Award from the U.S. Department of Education and the Commonwealth Compass Award from the state.

His multi-pronged plan for the city’s school system includes instituting programs in every school similar to those he developed at Glenwood, changing the way subjects are taught, as well as developing an individual plan for every student at risk. “You have to believe that this work can be done and then have a deep commitment to do the hard work necessary to execute it,” he said.

However, he knows this will take time, and says the entire community is needed to ensure success. “We need the business community and faith-based communities to support the schools,” Warwick said. “Education is the key to the success of the future of our community. And the only way Springfield will be successful is if we have a highly effective school system. The future of the city depends on it.”

Rounded Perspective

Warwick grew up in Springfield, and his entire career has been spent in the city’s schools, making him uniquely aware of the challenges and opportunities.

“I absolutely believe that every student can learn, and I want to meet every student’s needs so they can reach their potential,” he said. “I have a ‘no child left behind’ mentality, so every student who is struggling will have an individual plan that will be monitored to ensure they are getting the services they need.”

He began work as a substitute teacher at age 21 after graduating from Westfield State College. After that, he was hired as a special-education teacher for severely emotionally disturbed students in an alternative middle- and high-school program situated in the Springfield Boys and Girls Club. “A lot of them were in the juvenile justice system,” he recalled.

He spent 10 years as a teacher and two years as a special-education coordinator, then was named supervisor of the department.

“There were tremendous challenges in trying to meet all of the needs of different populations with finite resources. So I did a lot of program development,” Warwick explained, adding that he was able to reduce the number of students in private schools or residential facilities. “The whole idea was to keep the kids in the least restrictive environment and still provide them services, which also freed up money that could be spent on all students.”

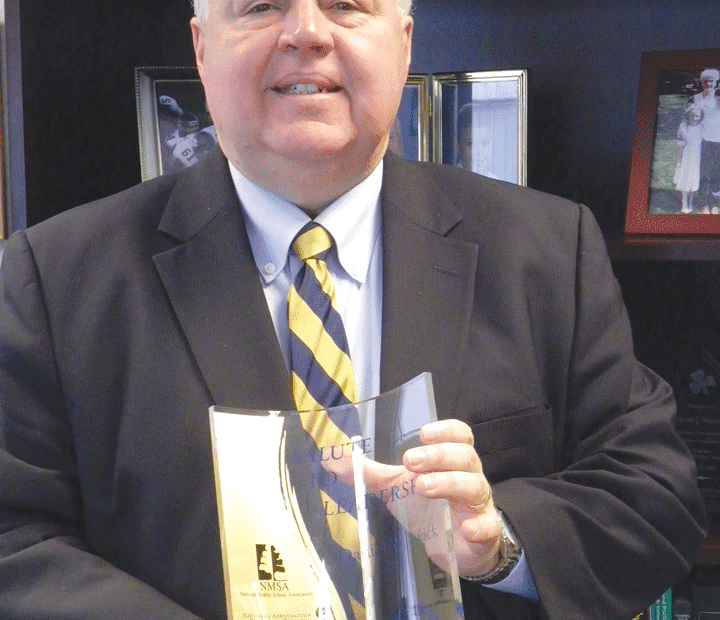

Daniel Warwick shows off the National Blue Ribbon School Award, one of many honors he earned during his tenure as principal of Glenwood School.

Over the past few decades, Warwick has held many roles in the school system. One of the most pivotal was his 13-year stint as principal at Glenwood School, where he achieved extraordinary success. “I did a lot of research and had a reading coordinator and an instructional leadership team,” he said, adding that measures he instituted were later adopted across the district.

Warwick went on to serve as an assistant superintendent from 2004 to 2008. “One of my key roles was special education, but I also supervised one-third of the city’s schools and dealt with operational issues, such as budgeting and staffing allocations,” he said. “During that time, the schools in my zone made twice as much progress as the other zones.”

He said he worked closely with Special Education Director Mary Anne Morris to improve services and set up quality programs.

When he was named assistant superintendent for all of the city’s schools in 2008, he implemented evaluations of school principals and led the district’s efforts in obtaining state approval for construction of a new vocational high school.

Before being appointed superintendent, he served as deputy superintendent for more than a year. He managed the district’s budgeting team and successfully led contract negotiations with bargaining unions. Warwick also spearheaded the redesign of the district’s lowest-performing schools, which resulted in such exemplary improvements that state officials hailed Springfield public schools as a model for rapid transformation.

Multi-pronged Approach

Warwick said he put a lot of time into developing his five-year plan for the future. It contains four key points and is a result of his work with several superintendents, a great deal of research into best practices, and his own experiences and observations.

The first key is to coach, develop, and evaluate educators with the goal of improving instruction.

“All of the research that has been done talks about the importance of quality teaching,” he said. “And teacher effectiveness and strong instructional leadership are the key variables in raising student achievement.”

The state recently issued new regulations that change the way schools are evaluated, and Warwick said he was aware of what they would be when he created his plan. However, each school district has to implement changes based on negotiations with its teachers’ unions.

This has been done in Springfield, and one important change is that principals will be able to conduct unannounced observations in the classroom. “The focus will be on improving instruction, which will require a tremendous amount of training because principals will have to become instructional experts, along with the teachers. But it will make a huge difference,” Warwick said.

The state will also begin providing data about individual student achievement. “This will help us judge the quality of teaching and will play a major role in the goal of improving instruction,” Warwick said.

The second area of focus will be to develop and implement what Warwick refers to as a “world-class, 21st-century curriculum that will deliver on our promise that all students graduate college and are career-ready.”

It will require a strong focus on literacy as well as a multi-tiered system of support for instruction at all levels, backed by ongoing assessments. “There will be an entirely new curriculum taught in a new way that will be a challenge for every community in Massachusetts,” he said.

Warwick explained that the new core standards are far more rigorous than what was demanded in the past. “It will require teachers to teach differently by putting more emphasis on higher-order thinking skills, reasoning, and literacy skills. The state can issue mandates, but only quality implementation at the district level will make them a success.”

Teams of teachers have been meeting in Springfield and will continue collaborations for the next 18 months. But Warwick expects it will take three years and a great deal of professional development to get the new system up and running.

What makes it especially challenging is that Springfield’s high poverty rate generally leads to poor attendance. In addition, the school population includes a high incidence of English language learners, and families move frequently, which results in great gaps in learning.

“We also have a number of homeless children and students who are in the custody of Child and Family Services,” Warwick said. “Poverty results in social and emotional issues, and families typically don’t get help for them.”

The School Department has been working with the Irene E. and George A. Davis Foundation to offer more preschool classes, which are critical to student success, especially since many students entering school don’t have the language skills they need.

The city also has 10 schools with a Level 4 state rating, which means they need significant improvement.

But the third component to Warwick’s plan will help to address that, as it involves continuous improvement based on a new system of data dashboards.

“The dashboards will allow educators to see how every youngster in their class is doing compared to students across the state and the country, and allow them to make instructional decisions based on the data,” he said.

There will also be something called the Dropout Early Warning Indicator System, which factors in attendance and discipline problems, beginning in kindergarten.

The final key is to remove obstacles to learning and student achievement. This will include positive behavioral interventions and individual plans for at-risk students. Warwick said clinical counseling; an expanded array of afterschool, summer, and night-school programs; homework help centers; home/school parent liaisons; parent and community focus groups; strengthening alternative school models; and adding recreational supports, such as sports, will make a difference in “battling the negative effects of poverty.”

Continuum of Progress

Warwick said he expects to receive new data from the state this month about how his district is faring.

“I’m sure it will show we are moving in a positive direction; we plan to intervene one school at a time, and knowing what has to be done is very helpful,” he said.

“When I took the job, I understood what the district needed,” he continued. “It will take an enormous amount of work to implement it, but we will continue to remove obstacles to learning and student achievement. It’s a privilege and an honor to serve as superintendent, and I take the responsibility very seriously.”