Author Keeps Memories Alive of Lost Quabbin Towns

Gone but Not Forgotten

Elena Palladino in the house that inspired her book, Lost Towns of the Swift River Valley.

Elena Palladino recalls that, when she and her husband first walked through their stately white home in Ware, they noted that some of the pieces didn’t really seem to fit.

Indeed, the home is Colonial Revival in style, but many of its fixtures, including the pocket doors with ornate brass pulls, were Victorian. Their presence — which made the home even more attractive, and intriguing, in their minds and helped compel them to buy it — presented somewhat of a mystery.

One that was solved when one of their new neighbors referred to the property as the ‘Quabbin house.’

Palladino would eventually learn that this home was built by Marion Andrews Smith, who had lived in Enfield, one of the four towns flooded and essentially wiped off the map to build the Quabbin Reservoir; Dana, Greenwich, and Prescott were the others.

“It’s a very beautiful place. But I do think it’s important to remember that’s it’s a beauty that comes from the loss of those towns and the loss of community.”

Smith, as Palladino would also learn, was the last surviving member of a prominent mill-owning family that actually had a section of Enfield, known as Smith’s Village, named after them. Smith certainly didn’t want to leave Enfield, a town that she and other family members were very involved with, and she was one of the last residents to depart. She wanted to move the large Victorian home in which she lived to another location, but it wasn’t logistically feasible to do so. So she took what she could with her and made those pieces — everything from doors to molding; floorboards to wainscotting — part of the home she built in Ware.

But Smith’s story did far more than solve a mystery surrounding Palladino’s new home.

It inspired her to want to dig deeper into the lives of those who, like Smith, were told to pack up and leave and then watch as their community was obliterated to bring much-needed water to the fast-growing city of Boston and its suburbs. It inspired her to want to know more about what those final years, months, weeks, days, and even hours were like.

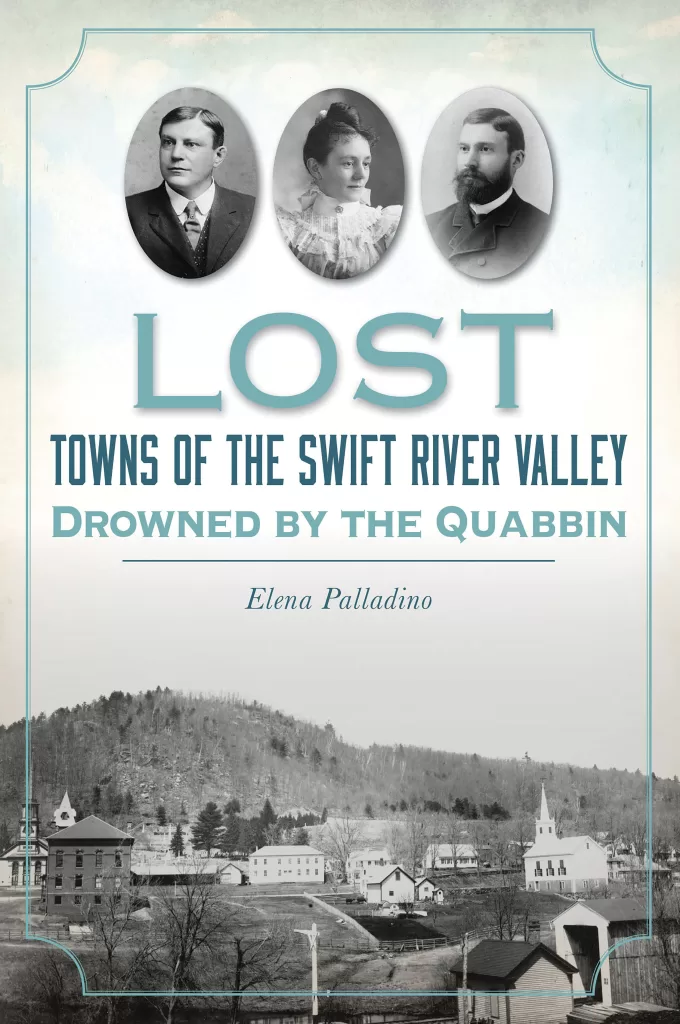

So, Palladino, secretary to the board of trustees at Smith College, started the research that would eventually lead to her first book: Lost Towns of the Swift River Valley: Drowned by the Quabbin.

It tells the stories of three individuals who were forced to leave their lifelong homes to make way for Boston’s reservoir — Smith; Willard ‘Doc’ Segur, the valley’s beloved country doctor and town leader; and Henry Howe, Enfield’s postmaster and general-store proprietor.

The book came out in late 2022, and over the ensuing year, Palladino has crisscrossed the state on a book tour of sorts that took her to libraries and historical societies. She talked about her book and the research that went into it, but also about her home and the connection it provides to Smith, and an intriguing bill now in committee that seeks regional equity and recompense for the Swift River Valley and its people (more on that later).

Through the book and the talks, she said she believes she’s created a greater understanding of all that was lost to build the Quabbin. Most understand fully what was gained, she added, but her stories help convey the price that came with this 20th-century engineering marvel.

Elena Palladino says learning the story of her Ware home inspired her to dig deeper into the lives of those displaced by the Quabbin.

It is this profound loss that she now feels each time she visits the Quabbin, which is only 10 minutes from her home.

“It’s a very beautiful place,” she said. “But I do think it’s important to remember that’s it’s a beauty that comes from the loss of those towns and the loss of community.”

For this issue, BusinessWest talked with Palladino about her home and her book, but mostly about the Quabbin towns and why, 86 years after Swift River Valley residents gathered for a farewell ball to mark the demise of their communities — “A Last Good Time for All” was how it was billed — it’s important that their stories never be forgotten.

Flood of Memories

Palladino has never met Marion Andrews Smith — she was born decades after Smith died.

But she feels a very powerful connection to the woman. Living in the home she built and spent her final years in is a big part of it, obviously, but there’s much more.

“It started as a personal project, and the initial research was mostly on our house. As I learned more about Marion … it seemed like every bit of research led to more.”

Indeed, as she came to know more about Smith through her research and then through meetings with Marian Tryon Waydaka, whose parents were Smith’s groundskeeper and chauffeur — and named their daughter after their employer — she came to fully understand both Smith’s taste in home furnishings and her incredibly strong will in the face of not only losing her home to a public-works project, but so much more.

She learned, for example, that Smith had family members who died in 1928, 1929, and 1932 and were buried in the valley, knowing full well they would have to be eventually moved elsewhere as the reservoir became reality.

“It could have been denial or defiance; it may also have been that she hadn’t decided where else she would like to move,” Palladino said. “But I thought that was a very interesting decision.”

She also learned that Smith was one of the very last residents to leave in the summer of 1938 and never did sell her property to the state; her land and home were taken by eminent domain, although she did eventually settle with the state.

Palladino grew up in Sturbridge, just east of the Quabbin, and her father and brother loved to fish the reservoir. So, like most who grew up in the 413, she knew the basics about how that resource was created and how four towns disappeared in the process.

It wasn’t until she and her husband bought the house on Highland Street after she took the job at Smith College — and they learned more about the home and the woman who built it — that her subtle interest in the Quabbin towns and the people who lived there became a fascination, and the subject of a book.

“The book started as research — I’ve always loved history and old homes — but then, because I was able to find out so much about Marion and her story was even more fascinating because it was integrated with the Quabbin towns, it became a much bigger project than I ever thought it would be.

“It started as a personal project, and the initial research was mostly on our house,” she went on. “As I learned more about Marion … it seemed like every bit of research led to more. Because she was from such an important family, there was lots to find about her; she was very involved, as were her family members, in various town organizations.”

Palladino took full advantage of the many resources available to those who wish to know more about the Quabbin towns and those who lived there, including a large collection at the UMass Amherst Library; the Swift River Valley Historical Society in New Salem; the Visitors Center at Quabbin Park in Belchertown; various scrapbooks; several books on the subject, including Donald Howe’s Quabbin, the Lost Valley; and meeting minutes from various organizations, including the Quabbin Club, a women’s club in the valley that existed from the late 1800s until the towns were disincorporated.

The Plot Thickens

Palladino’s book focuses on three of the last residents to leave the valley, and through those stories she conveys those final days through their eyes.

“There are many great books about the Quabbin, but this one is a little more personal in nature,” she said. “I was most intrigued by what it like for Marion, and any of the people who lived there, to have to leave; it’s a more personal side of the story.

“It was a long process,” she went on. “The Ware and Swift River Acts were passed in 1926 and 1927, and even before that, for about 30 years, the idea of an enormous reservoir was out there — it was discussed. From 1895 on, people knew this might come to pass and that a reservoir might be built here. When it finally became real, it was devastating for the people who lived there, but it also didn’t feel quite real because there was such a long period of time during which the towns were destroyed, and the dam and the dike were built — it was about 10 years.”

She said some left quickly after their homes were purchased by the state, while others who sold leased them back and stayed in the valley while deciding where to go next. And then, there were some who stayed until the very end.

“I think that must have been a difficult choice to make,” Palladino told BusinessWest. “By 1938, it was a scene of destruction; by then, many homes had been demolished and burned, all of the trees in the valley had been cut down, all of the brush below the water line had been cut and burned, and the buildings that were still standing in 1938 were quite dilapidated because they weren’t being cared for.

“Their town would have been unrecognizable,” she went on, adding that, despite all this, some did stay to the bitter end.

Palladino has tried to convey the hardships and emotions experienced by all those who lived through the demise of the Quabbin towns during talks about her book, more than 40 of them, over the past year or so.

“It was wonderful to speak locally, to people who know a lot about the Quabbin and live near the Quabbin, but it was also good to speak in Eastern Massachusetts towns where the story is less well-known,” she said. “There are plenty of people who know that their water comes from the Quabbin, but far fewer who really know how the Quabbin came to be.”

Elena Palladino wants everyone who visits the Quabbin — or ever drinks its water — to contemplate the loss and sacrifice involved in its creation.

Through her talks, she has also made people aware of legislation, now in joint committee, that would, among other things, establish a Quabbin host-community fund through a 5-cent levy on every 1,000 gallons of water drawn from the reservoir.

“It’s pretty modest — it would only raise about $3.5 million a year,” she said. “But those funds could be used by the towns around the Quabbin for infrastructure and other capital improvements.”

The Loss Column

Palladino wasn’t at the farewell ball in 1938, obviously. But in some ways, she feels like she was.

Through her research, she has come to understand, as perhaps few can, what it was like to be at Enfield Town Hall when the clock struck midnight, and this wasn’t actually a town anymore.

It was part of a valley that would, over the next several years, be flooded with more than 400 billion gallons of water.

That ball, and the many extreme forms of loss experienced by those who were there — and all those who lived in the Quabbin towns — is what she thinks about when she visits the reservoir.

And she implores all those who visit or even drink the water to do the same.