Peter Gagliardi, President and CEO of Way Finders

He’s Spent a Career Bringing Home the Power of Collaboration

Like most school teachers working in the early ’70s, Peter Gagliardi needed something to do during the summer — not just to keep him busy, but to help with cash flow during those 10 weeks when there were no paychecks coming in.

Early in the summer of 1973, his search for such an employment opportunity took him to a nonprofit called Rural Housing Improvement Inc. in Winchendon. After being told there were no part-time, temporary jobs to be had at the agency, he was further informed of a full-time, permanent position as director of property management that he might pursue if he was interested.

After doing a little soul searching — OK, a lot of soul searching — he convinced himself that he was interested.

“I had just signed a tenured contract, but I resigned and took a job with an organization that had secure funding for 30 days,” he said in a voice that didn’t accurately reflect the sizable risk he was taking. “And I’ve been doing housing ever since.”

It was a big decision for the Gagliardi family, and, as things would turn out, a big one for countless other families as well.

Indeed, that job with a fledgling nonprofit would, as he said, lead to a career in housing. But actually, it’s been a career in much more than that. In the nearly 30 years he’s been president and CEO of Way Finders, the agency formerly known as HAPHousing and before that the Housing Allowance Project, he has helped to greatly expand both the mission and the nonprofit’s influence far beyond its original charge — providing housing vouchers for those in need.

“I had just signed a tenured contract, but I resigned and took a job with an organization that had secure funding for 30 days.”

While it still helps individuals and families secure a roof over their heads through vouchers and creation of new affordable-housing projects, it now helps people in many other ways, as its relatively new name suggests.

It helps them secure employment through job-training initiatives, for example, and also enables individuals to become homeowners by helping them save money, improve their credit, and take the other steps needed to buy a house. And it has stepped forward to help change the trajectory of entire blocks and neighborhoods.

That was the case on Byers Street in Springfield, a half-mile-long stretch that borders the Springfield Armory property and, ironically enough, sits across Pearl Street from Springfield Police headquarters. Ironic because, by the late ’90s, Byers Street had become a hot spot for crime and, in most all ways, a blighted area.

It was (note the past tense) defined by perhaps its most famous, or infamous, piece of real estate — the Rainville Hotel.

Peter Gagliardi stands in front of the Way Finders-managed properties on Byers Street in Springfield, an area that has become a “different place” since the agency became involved.

“It was notorious,” said Gagliardi, flashing back 15 to 20 years, adding that it had become a center for drug dealing and other illegal activities, and just one of several properties that were causing problems for abutters that included Springfield Technical Community College, the Quadrangle, St. Luke’s Home (operated by the Sisters of Providence), the Diocese of Springfield, the Armory Street Commons apartment complex, and others.

HAPHousing stepped forward, partnered with other agencies (more on this later), and changed the fortunes of that area by taking down some derelict buildings and fixing up others. Today, it manages the Rainville, now an apartment complex, and several other properties, and the change on the street is palpable.

“You’re seeing other property owners on the street investing in their homes,” said Gagliardi, pointing out such initiatives as he walked the length of Byers Street with BusinessWest recently. “It’s a much better place now.”

The same can be said of the Old Hill section of the city, another area where Way Finders worked, again in partnership with other agencies and especially Springfield Neighborhood Housing Services, to bring about positive change in many ways. Dozens of new homes have been built, dozens more have been renovated, and scores of vacant lots have been put to better uses. Most importantly, residents are taking pride in their neighborhood — as well as responsibility for it — and the fabric of that neighborhood is becoming stronger.

“You’re seeing other property owners on the street investing in their homes. It’s a much better place now.”

“There’s always more to do, but Old Hill is a different place,” said Gagliardi. “Since the houses were built that we’ve been involved with, people are choosing to buy homes there; that was just not happening before.”

In a way, Byers Street, Old Hill, and what’s happened in those areas have become living symbols of Gagliardi’s energetic and imaginative approach to fulfilling and expanding the stated mission at Way Finders — “to light pathways and open doors to homes and communities where people thrive.”

And they serve to help explain why he has long been a real Difference Maker in this region.

Keys to Success

They call them ‘Success Stories,’ and that’s pretty much an understatement.

These are poignant vignettes, if you will, created to help convey the many ways that Way Finders has evolved as an agency and how it has helped change the lives of the people it has touched.

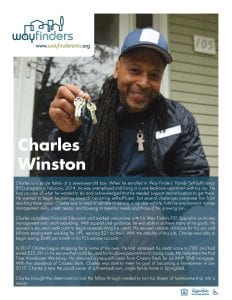

People like Charles Winston, the single father of a 7-year-old boy, who was unemployed and living in a one-bedroom apartment with his son when he enrolled in Way Finders’ Family Self-sufficiency (FSS) Program in 2014. He knew what he wanted to do — buy a home of his own someday — but also knew he had a laundry list of things he needed help with, from reliable childcare to a dependable vehicle; from full-time employment to credit repair. Long story short, Way Finders and its FSS program helped with all that. He secured a job with UPS, improved his credit score to 738, saved $22,391 in an escrow account established for him to buy a house, and in 2017, he became a home owner.

Peter Gagliardi and his staff at Way Finders have helped write many different kinds of success stories in recent years.

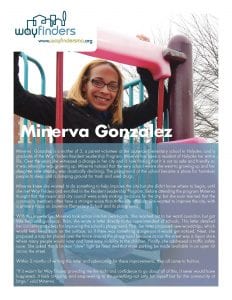

And also people like Minerva Gonzalez, who witnessed a sharp decline in the neighborhood in Holyoke in which she grew up and was now raising a family, and became determined to do something about it, only she didn’t know where or how to begin.

After enrolling in Way Finders’ Resident Leadership Program, she soon learned that community leaders often have a stronger voice than city officials. And she used hers to bring about change at H.B. Lawrence Elementary School and, specifically, a host of improvements to its playground.

You don’t see Peter Gagliardi’s picture accompanying these success stories. Instead, you see Charles Winston proudly holding up the keys to his house, and Minerva Gonzalez sitting atop a piece of playground equipment at her kids’ school.

But he had a big hand in writing them, a pattern that began way back in 1973 when he decided to leave the classroom and take that full-time job with Rural Housing Improvement Inc.

But our story actually begins several years earlier, when Gagliardi was attending college. He met a volunteer with VISTA (Volunteers in Service to America) who was working in his hometown of Athol, and she introduced him to a housing problem he never knew existed.

“She showed me some atrocious housing conditions that people were living in and really brought the issue home,” he recalled. “I never thought about us having poor people as neighbors — they were all friends. I didn’t think about people living in really terrible living conditions, but there were some, and there weren’t a lot of alternatives for people.

“I learned a little bit, and then I went off and finished school, did the teaching thing, and along came a job that was pretty much serendipity,” he went on, retracing the start of his new career. “It got me involved in housing, and it became clear pretty quickly that this is where I should be.”

At Rural Housing Improvement Inc., Gagliardi worked for a boss who gave him what he called “a wide-open portfolio,” and he took full advantage, spending 13 years at the organization, rising to the rank of associate executive director, and, most importantly, learning a number of lessons he would apply later in his career, starting with his next stop.

“Along came a job that was pretty much serendipity. It got me involved in housing, and it became clear pretty quickly that this is where I should be.”

That would be at the recently created Mass. Housing Partnership, part of the Executive Office of Communities and Development, in 1986.

There, he worked under Amy Anthony, who was, ironically enough, the first executive director of the Housing Allowance Project and would become a titan within the affordable-housing industry, transforming Massachusetts into a national leader in that realm (she passed away last December).

Gagliardi was recruited to be director of field operations for the Mass. Housing Partnership, and his job was to work with communities across the state to develop what were known as ‘local housing partnerships.’

Peter Gagliardi says the Healthy Hill Initiative in Springfield’s Old Hill neighborhood is just one example of the power of collaboration.

“The concept was, if you bring people together from different sectors and start focusing on the problem, then the interaction will add to the value of the work that you do,” he explained. “You have the private sector, the public sector, and representatives of the community … you’re tackling a common problem, and by doing it together, you get a better result than if any one of those sectors tried to do it on their own.”

And results were achieved, he said, adding that Massachusetts soon set the tone for affordable-housing programs nationwide through imaginative, partnership-driven initiatives that changed the landscape in all kinds of ways.

“That was a very dynamic time in housing in Massachusetts,” he recalled. “The governor [Michael Dukakis] was putting resources into it — these were the days of the Massachusetts Miracle — and allotted programs were created in Massachusetts, many of which still exist today,” he told BusinessWest. “We became the envy of all the states in the country with the variety of programs we had and the effectiveness of those programs.”

Living Proof

Gagliardi would eventually take the role of director of Private Housing at the Mass. Housing Partnership and would stay in that role for roughly a year.

By the end of 1990, however, the Dukakis administration was coming to an end, and he was looking for his next challenge.

He found it as president and CEO of the Housing Allowance Project, a position that, in many ways, took him back to his work with Rural Housing Improvement Inc. and the front lines of the housing problem in the western part of the state.

Over the past 28 years, the agency has grown and diversified its portfolio of services largely out of necessity, in a way that makes its mission more holistic in nature and worthy of that name Way Finders.

Gagliardi put all this into some kind of perspective:

“I think the most significant thing we’ve done is bring together a variety of services, all of which are complementary,” he explained. “We’ve built the strength and the reputation to take on new challenges as they arise. More than any one specific program, what we’ve been able to do is generate impact for the community and the people we work with across a wide range of programmatic activities.”

To explain this expansion of the mission, he returned to Byers Street, literally, where he pointed to the buildings, including the Rainville, that have been transformed from eyesores into attractive affordable housing, and talked about how it happened.

“This was one of Springfield’s darkest hours in a lot of ways,” he said, while setting the tone and explaining how Byers came to be the way it was. “Jobs had been declining for many years, people left their housing, places were vacant and abandoned; it was very difficult circumstances.”

The agency’s work there is a solid example of the importance of partnerships and bringing together groups with common goals to accomplish something they could not have done on their own, he said, adding that efforts to revitalize the area led to the creation of the Armory/Quadrangle Civic Assoc., which is still active today.

“We took the experience of doing some affordable-housing development, but in an urban setting, to use it as a way of bringing positive change to a neighborhood,” he said, adding that the agency brought various officials and groups to see what was done there. And the results would inspire an even bigger initiative.

“When we had an open house for our second project there on Byers Street, we brought some people down in a bus from the Old Hill neighborhood,” he recalled. “And I can remember the head of the Old Hill Neighborhood Council saying, ‘why can’t we do this in my neighborhood?’”

Soon thereafter, they did, in what became perhaps an even better example of the power of partnerships.

By the early 2000s, there were 150 vacant lots in Old Hill, a neighborhood in the vicinity of Springfield College, which represented maybe 10% of all the residential lots.

“We knew we couldn’t just go in, do a couple of houses, and make a difference — we needed a different strategy,” he explained, adding that, in collaboration with a host of partners, including the college, Habitat for Humanity, the neighborhood council, Springfield Neighborhood Housing Services, Revitalize Community Development Corp., and others, a plan was crafted to acquire many of the vacant lots (often from the city in tax title) and putting new homes on them.

Meanwhile, many other homes were rehabbed, and a host of agencies came together for what became known as the Healthy Hill Initiative, a project focused on two of the primary social determinants of health — public safety and access to physical activity.

“The secret to success, in my mind, is collaboration,” he told BusinessWest. “One of the things that I’m mindful of is that we would not have done any of this on our own.”

He was talking about Old Hill, but that sentiment applies to many of the initiatives the agency involves itself with, and collaboration is just one of the managerial mindsets that Gagliardi has brought with him to work for the past 45 years or so.

“We’ve built the strength and the reputation to take on new challenges as they arise. More than any one specific program, what we’ve been able to do is generate impact for the community and the people we work with across a wide range of programmatic activities.”

Overall, he said his goal has been to hire people who, like him, have a passion for this kind of work and can realize that, while the work is often difficult and bound tightly in red tape, there are many rewards.

“We’re working here because, at the end of the day when we go home, sometimes tired from all the complexities of the programs we run, we can take pride in the fact that, because of what we did today, somebody is in housing they wouldn’t otherwise have had,” he told BusinessWest. “It might be a homeless family has found a place to call home or a family that was in danger of being evicted has solved their problem. That’s much different than coming home and saying, ‘well, I made another buck for the shareholders,’ and that’s what keeps us coming back the next day.”

Looking back on that fateful decision he made back in 1973, he said he has no regrets at all and is simply thankful for that bit of serendipity.

“It’s been good work,” he said with a wide smile on his face. “There is where I should have been.”

Bottom Line

As he talked about his work with Mass. Housing Partnership, Gagliardi took a few minutes to reflect on the many ways Amy Anthony influenced his career.

“She was inspiring,” he told BusinessWest. “She was full of energy and open to ideas. I would go to her with an idea, she’d think about it, we’d talk about it, and she’d say, ‘OK, I like it; run with it.’”

One could use many of those same descriptive words and phrases when talking about her eventual successor. Also full of energy and open to ideas, he has built upon her legacy and helped write countless success stories like those mentioned earlier.

And he’s come a long way since he stepped into the offices of the Rural Housing Improvement Inc. looking for a summer job. Instead he found a career and, indirectly, a path to the stage at the Log Cabin on March 30, where he’ll be honored for what he has truly become.

A real Difference Maker.

George O’Brien can be reached at [email protected]